The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon (MMCA Gwacheon) opened the exhibition ‘Olympic Effect: Korean Architecture and Design from 1980s to 1990s’on the 17th of December, 2020. The exhibition observes the transformations undergone and the legacies left by Korean cities, and their architecture and design, as called forth by the national mega-event, the Seoul 1988 Summer Olympics (hereinafter the Seoul Olympics). The exhibition, composed of four sections with an additional epilogue and prologue, draws on archival evidence to amplify the breadth of an event that had been dismissed as a one off event in a multi-dimensional way, and attempts to fill gaps in knowledge with new interpretations by young artists. We toured the exhibition, which illuminates the internal and external developments across the fields of architecture and design from a professional perspective, and talked with Chung Dahyoung (curator, MMCA).

interview Chung Dahyoung curator, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art × Bang Yukyung

Jin Dallae & Park Woohyuk, Master Plan: Harmony and Progress, 12 channel video, sound, graphic, installation, Variable dimension, 2020

Bang Yukyung (Bang): This is the last exhibition to be featured at MMCA Gwacheon in 2020. Over the last decade, you have approached a variety of themes and methods regarding Korean architecture and design at the MMCA, and you must often have the question ‘Why this focus on the Olympics, now?’ directed at you?

Chung Dahyoung (Chung): Like any other public authority, the MMCA also plans and announces its exhibitions a year in advance. This exhibition was planned to target the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 (hereinafter the Tokyo Oylmpics) season with the intention of ‘reflecting on the urban heritage left by the Olympics’. Of course, we didn’t imagine at the time that the Olympics would be postponed. (laugh)

Bang: Did the postponement of the Tokyo Oylmpics and the continuing global pandemic impact the direction or planning of the exhibition?

Chung: Few aspects were altered in terms of theme or content. From the outset, the focus of the exhibition was to be on daily life rather than on the Olympics itself. While we could have featured a chronological record, in discussing architecture and design of the 1980s to the 1990s, the available domestic resources and research were too weak or as too much of a remove. This was why we observed everyday life through the lens of Seoul Olympics mascot, on drafting paper and behind measuring city or architectural plans through large underlaid maps is the same. If artist groups possess unique professional images as ‘creators’, perhaps we can say that our impression of design groups involved in planning derives from such acts? Of course, each field has its own unique gestures, representative mediums and results. In a greater sense, there is a commonality in the sequential processes between creating mock�ups and diagrams. Interestingly, the 1980s and the 1990s formed a time in which the profession was being cultivated in the most plentiful sense, presenting tangible results. I wanted to show how the rules, regulations and logic behind these results could, in themselves, be seen as advanced and aesthetically pleasing.

Bang: In that case, how did you define the scope of subjects demonstrating the practices of such a profession, and therefore the subjects informing the exhibition?

Chung: The Seoul Olympics could be seen as an event that dynamised the creative vision of the architectural and design fields as a single industry in Korea. Centring on this idea, the initial phase of exhibition planning involved defining a ‘Seoul Olympics Area’ which would be visible during the event. These are spaces in the city that underwent major change as a result of the Olympics. a symbolic event, The Olympic Games. It became a double-sided medium through which to understand architecture and design within the context of a particular epoch. The experience of the pandemic has motivated people to reflect on their familiar living environments, and in a way, this change has aided in the understanding of the exhibition.

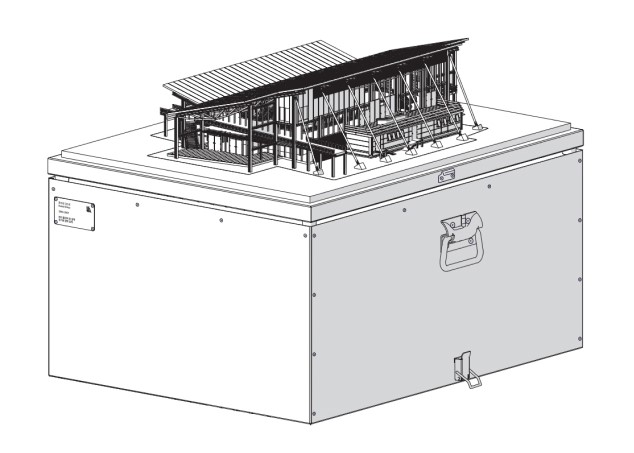

Model of the Seoul Olympics Main Stadium, Made by Kee Heung Sung, 145×145×30cm, Kee Heung Sung Museum Collection, 1980s

Bang: If Part 1: The Olympic Effect presents the political and social transformations surrounding the Olympics in a compact way and shows actual images of the Olympics, Part 2: Designers, Organizations, and Processes introduces the as yet untold stories of the designers, organisations, and production processes. What perspectives lead to the dual realms of architecture and design intertwining?

Chung: In general, most architecture exhibitions deal with the issue of ‘representation’. They tend to focus on architectural form, the modeling of space, or its aesthetic beauty. However, this exhibition focuses on industrial production and results, and how, when architects and designers are committed to their profession, results can present themselves in a range of ways such as blueprints, graphics and models. Personally, I wanted to reveal that a common grammar exists in ‘planning’, from graphic design to urban design. All this is to say that the logical structure behind measuring out Hodori, the The main subjects were apartments or large scale apartment blocks which introduced new concepts to design at the time, like the Olympic Seonsuchon Apt., infrastructure related to public transport, high-rise office space architecture like the 63 Building or the Korea World Trade Center, high-class accommodations to receive tourists such as The Shilla Seoul, Lotte Hotel Seoul, as well as cultural facilities like theme parks, for example Seoul Grand Park or the MMCA Gwacheon.

Seoul Model Shop. Diorama Seoul, 3D printing model, steel case, Variable dimension, 2020

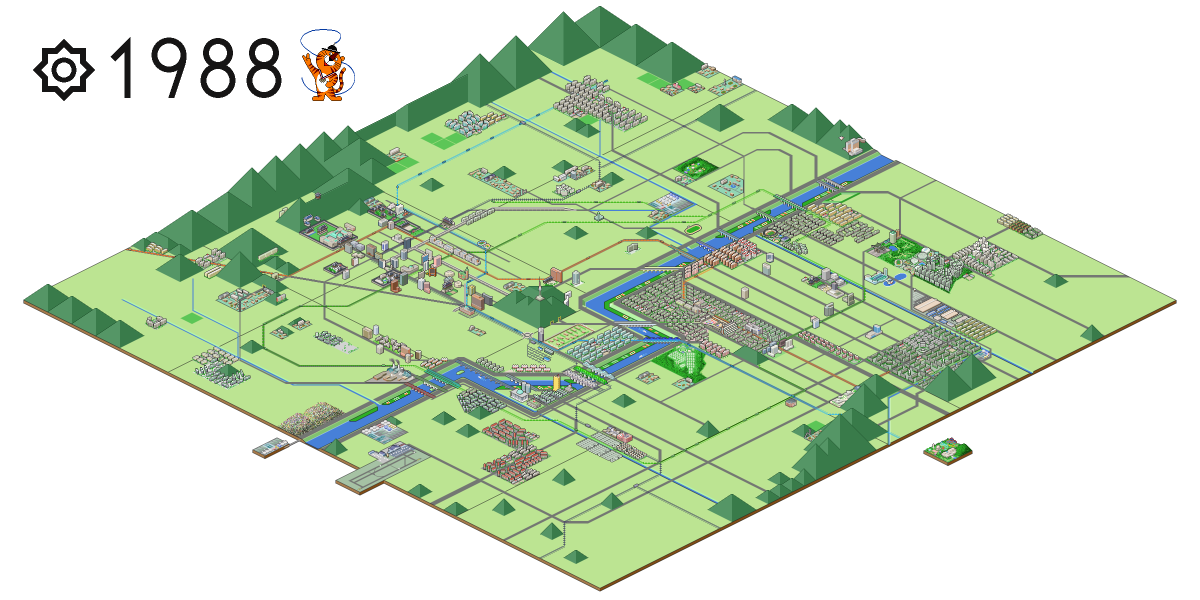

Sunwoo Hoon, Modularized 1988, detail view, Digital drawing, Variable dimension, 2020

Bang: Most of the participating artists were born after the 1980s, and did not directly experience the Seoul Olympics. Your approach also diverges from that of the fine arts, with fields of design and engineering standing between the realms of industry and the arts. Part 2 proposes fresh perspectives on the event by reading the epoch and its commodities using methods that differ from the conventional videos of interviews, such as Modularized of the webcartoon artist Sunwoo Hoon who drew a compact history of the city of Seoul, or the webcartoon Characterized which rereads the narratives of notable figures who instigated great change in industrial fields like architecture or design.

Chung: In fact, artists from across these fields were invited to participate. The Seoul Olympics up till now has arguably been interpreted and circulated throughout contemporary discourse through the binaries of ‘light and dark’ pressured by the logic of politics, economics and culture. I thought that repeating these stories would be too tedious. It felt like three decades would provide a sufficient temporal distance from which to discuss the Olympics with greater liberty, moving away from these oppressive frameworks. The generation born after the Olympics was free from self�censorship and consumer content that focused on the Olympics in diverse and interesting ways. Since these artists also work in commercial fields, it was possible to coordinate with them smoothly when commissioning work. They had a good understanding of the client’s demands. They also met with our needs for deadlines, basic tools for communication (drawings, documents, etc.) and the final results. Could we say that they are exceptionally competent in their vocations?

Bang: This ability to communicate also connects to the theme in Part 2, which focuses on the advent of major corporations and the process behind organisations seeking an internal logic, rather than on the work of individual artists.

Chung: I began curating the exhibition with the notion that the modern history of Korean architecture only had the 4.3 Group after the passing of Kim Chung-up and Kim Swoo Geun. Yet, haven’t mid and large-scale firms like JUNGLIM Architecture or Wondoshi Architects Group also led a thriving design community? These domestic architecture firms, who are paramount in the role of SOM in the US, have thus far remained unobserved in the history of Korean architecture. Archival sites recently created by some of these architecture firms should be examined under this new light. A personal win for myself in the organisation of this exhibition was meeting the former JUNGLIM Architecture based Jo Chanwon (director, buildingSMART Korea’s R&D Center) while studying the process of architectural digitisation. He owned extensive stories and resources related to the process of adopting computer-aided design. I had previously distanced myself from more technical fields, considering them as engineering, yet I realised that there is a need to deal with this in a more serious manner. I once personally presented thoughts on the working systems of Korean contemporary architects while studying architecture in the digital age through the keywords of ‘file and folder’. I felt that the initial stages informing such working processes are related to the process of adopting computer aided design.

Bang: It seemed that the spatial core of the exhibition lies in Part 3: Perspectives and Façades. A three-decade long gap in time lies between the archives, the photos by Koo Bohnchang, the models by Kee Heung Sung, the photos of Choi Yongjoon and the models of Seoul Model Shop.

Chung: This was also intentionally choreographed. Originally, the subtitle ‘Three Perspectives’ was introduced to signify an observation per epoch, but this was modified as it was felt that it would place too great an emphasis on chronology and as a result be interpreted as a retro exhibition. The exhibition space does not have many walls, and Choi Yongjoon’s photography was erected to form huge façades, with the models of 30 to 40 years past in front of them, and a small number of archival works related to the works arranged behind these walls. In particular, the photographs by Choi Yongjoon visually communicate with Koo Bohnchang’s Clandestine Pursuit in the Long Afternoon series, revealing a dramatic contrast in epoch. This black and white series is one of Koo Bohnchang’s lesser-known earlier works. He actually had the experience of participating as a designer in the Seoul Olympics at the time, and we also talked of how it felt that his older works were being called into the world little by little while preparing the exhibition. It felt like our record of an epoch was being read in a new light.

Bang: You have been working as a curator in the architectural field for 10 years now. In terms of epochs, it feels like you are completing a puzzle, beginning with the 1950s and working your way to the 1990s, epoch by epoch. What kindof significance does this exhibition have within the spectrum of exhibitions you have devised? What future exhibitions or research themes are you planning?

Chung: If the protagonist of the exhibition ‘Papers and Concrete: Modern Architecture in Korea 1987 ‒ 1997’(2017), which I curated for the MMCA Seoul was on ʻpaperʼ, should ʻconcreteʼappear as the protagonist in this exhibition. I liked the idea because it was an exhibition that complemented and referred to itself as reference. More recently, I have been preparing the MMCA Gwacheon renewal exhibition, and I have been searching for ways to curate the museum itself, rather than architectural curation or archives. I have also been searching for ways to apply big data, drone footage and virtual reality technology as means of curating exhibitions, rather than as a method to produce exhibition artefacts. The social scientist Shin Chunghoon (professor, Seoul National University) has noted that ‘if the past city was discussed through the perspective of Walter Benjamin, we should now observe the city through the perspective of Google maps, drones and 3D scanners’. I have been considering a diverse range of issues like such as if it is possible to read a space comprehensively when using devices like drones or 3D scanners as critical discourse, or to use the methods of collecting data for the present generation rather than for manual site surveys such as the research on the hanok in Gahoe-dong.

Exhibition views ⓒBang Yukyung