Propelled by the Saemaeul movement, Korea’s economic development was initiated by pursuing America’s economic development model as its reference point. By giving out low-interest mortgage loans, the US government promoted its one house per household policy to establish a system in which each household would live the rest of their lives paying off their loan interest while keeping the house as collateral. By following this economic course, they planned to encourage workers to engage industriously in economic activities and thus promote US economic growth. After Japan incorporated this residential economic system in their country, Korea followed suit in the 1960s. Because this housing policy based on America’s economic growth strategy was adopted by Korea as a way of boosting national economic development, fundamental questions such as ‘what kind of housing should be provided>’ and ‘what kind of houses should Korean people live in?’ were often overlooked, and the perception of houses as commodities gradually became pervasive in Korea.

The Transformation of Multi-Household Residences

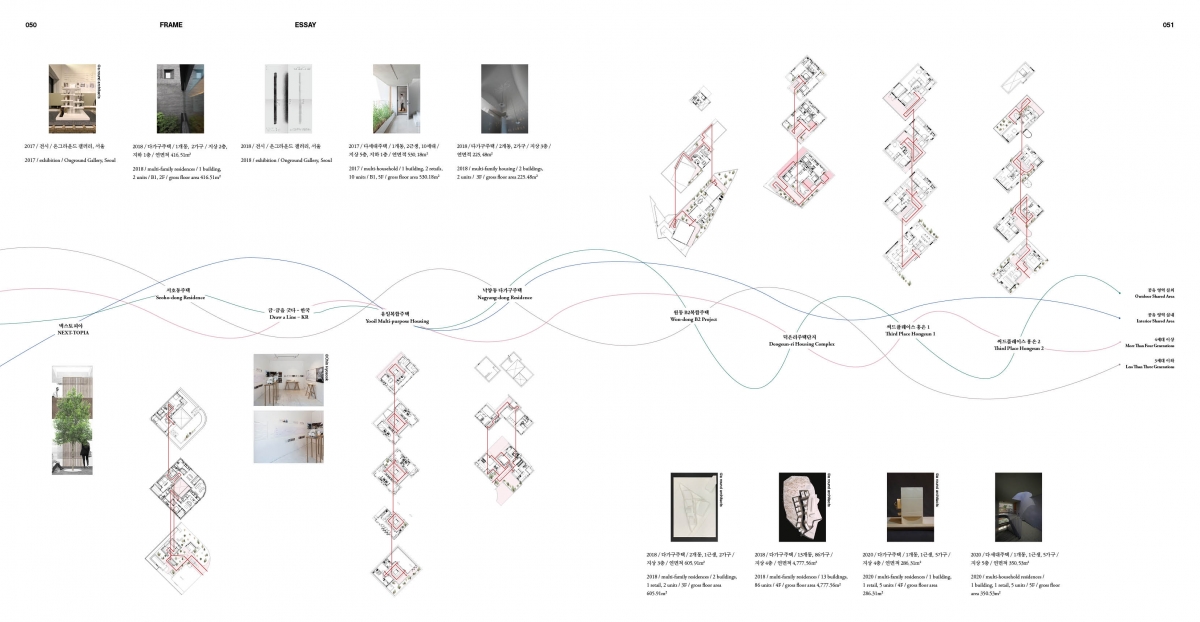

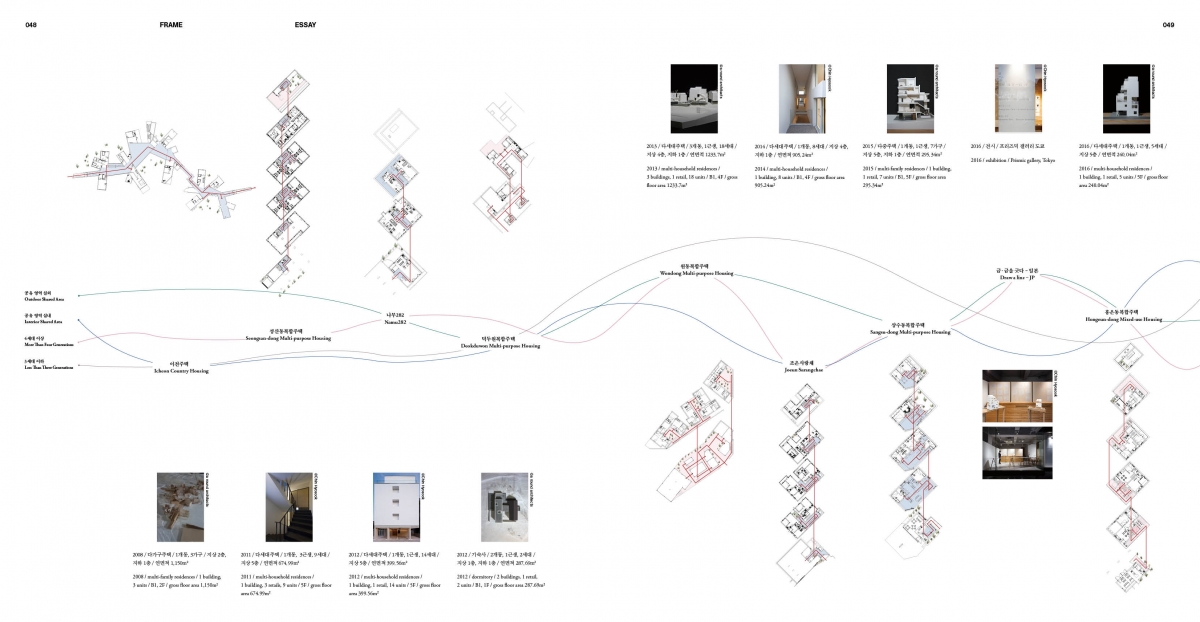

According to 2019 data from Korea’s National Statistics Office, the types of residence in Seoul were apartments (58%), multi-household residences (38%), detached houses and other less categorisable structures. Urbanisation in Seoul began after the1960s, and in order to resolve the exponential growth in population and the resulting shortage in housing, Seoul incorporated various policies such as the significant expansion and development of Gangnam and its satellite cities. Apartments that were developed in accordance to economic profit models replaced the downtown areas that embodied aspects of the city’s history and memories. From the 1970s, parking lots, rooftop terraces, and storage spaces in the sites for detached houses were transformed into illegal residences to hold multiple households due to a shortage in housing. As these illegal residences became more common, the government finally took action to resolve the problem by legalising the ‘multi-household residence’ model in 1990. From that point on, construction work for the multi-household residences that maximize floor area ratio gathered apace, and it is now assuredly the most profitable housing model.

The 1996 Istanbul Declaration

The Istanbul Declaration regarding UN Habitat II was a proclamation for the basic human right to live in safe housing. It calls for the universal aim to provide all human beings with appropriate housing that prioritises safe, habitable, equal, and pleasant living conditions that are also sustainable and productive. However, residences in Korea nowadays fall far short of the intentions behind this declaration that prioritizes quality of life over all else. Housing must be built to improve the living conditions of its inhabitants—that is, the people who live in it—rather than protecting the profits of its suppliers. There is a pressing need to change our perspective towards housing; instead of perceiving it as an asset to monopolise it must be viewed as social capital.

Changes to and Issues with Housing

As a sense of belonging to a region or a town was more highly valued than individual privacy in the past, houses used to be connected to one another via alleyways and narrow streets. The relationship between private houses and public roads was that they were relatively more open towards one another, and people were therefore more interconnected. However, as housing types turned into apartments, the life patterns also changed. Instead of yards that used to connect the house to the road, there are now gates that define boundaries. Similarly, corridors and staircases are now built with minimal area and width so that they is only just enough space for circulation of occupants. Also, as apartment districts were developed and managed as units, they became walled off from their surroundings. Such spatial isolation leads to social segregation. As neighbours come and go, according to their lease periods, it becomes difficult to form meaningful relationships with one’s neighbours, and it seems as though we have now forgotten how to communicate or to know what it means to live together.

Proxemics and Semifixed-Feature Space

We must ask ourselves a fundamental question regarding the meaning of connections formed within shared residences and search for a new understanding of what it means to be an aggregate body. We need to review our attitudes towards social detachment by striking up little conversations with neighbours. To do this, however, first we must alter our way of thinking towards the now long-forgotten understanding of what it means to be a member of a society and the value of being part of a community. Architects, especially, need to develop some interest towards the aggregate forms composed by housing districts, and they must contemplate what it means to participate in a human community and ruminate on the curious nature of its relationship. The first thing to discuss is proxemics. According to the sociologist Edward Hall, psychological changes can occur depending on the relationship and distance that one establishes with the other, and these changes can be respectively distinguished by distances of 0.5m (intimate distance), 1.2m (personal distance), 3.6m (social distance), and 7.5m (public space). When these detached individual realms form connections with one another, various kinds of relationships arise in response to the degree of detachment and level of connectivity. Therefore, in order to maintain and promote the quantity and quality of relationships, there must first be the proper identification and cognition of the kind of relationships that are shared between individuals—such as the kind of relationship, the feeling produced from the relationship, and the engaged act in the relationship—and the application of the appropriate amount of detachment from the situation, which is then to be followed by the architectural process of building physical relationships between houses. In a shared residence, each household must not only secure sufficient interior and exterior space for their own, but they should also secure the appropriate amount of distance for horizontal and vertical connections for public spaces of contact such as the corridors. Relationships do not grow closer just because there is little distance in between; rather changes in relationships arise from uniform distances and open-ended functions.

Affordances

The second task is to propose an open-ended function for coexisting. In the case of shared residences, the design is not limited to just the building’s form and space; rather, it should be approached with the aim of designing a physical platform for building social relationships. This is to encourage people to express themselves in the public realm in the same way as they might in the private home, and to share these expressions with others. A one-person household is bound to have the disadvantage of loneliness, but an open-ended programme like this in a small-scale shared residence can be psychologically helpful. Also, if a specific space is dedicated to this program, it naturally leads to community-building initiatives. OpenHouse and thirdplace Hongeun1 and 2 are examples of this. Another method is to develop interest towards affordances. This is about making predictions about the potential of certain materials or forms with yet undefined functions to find their functions themselves according to the given situations. If the users do not use them, they will be left there unused as simple objects. The experiment is precisely about that…

The Given Environment and our Future

We are currently going through a period of enormous change. Our society is being quarantined and our daily lives have been greatly transformed due to our unprecedented era of COVID-19. It is difficult to predict how long this situation will continue, or to estimate the starting point and impact of these changes. Teleworking will become the norm, and more and more time will be spent at home. One-person households will become even more isolated and disconnected, and this will bring about a widespread social problem. It is still difficult to answer questions such as ‘is it possible to live alone in a city?’ or ‘do we have to quarantine ourselves from our families?’, but it is obvious that the way of using houses will be different when compared to that of the past. Deciding on the housing method and the type of housing is a matter for the government, but the task of expanding the available options of housing methods is the responsibility of the architect.