‘One of our friends once told us that he had a chat with a local taxi driver about Alvar Aalto for about 40 minutes when he visited Finland. We were envious. Could it be possible for us to experience something similar here someday, too?’ This is what Vince and Irene envision. As the co-directors of the publication studio erosis, they hope to see a dissolution of the boundaries between professionals and non-professionals in the fields of art and design. In 2019, they began publishing their Manuscripts series, which features the translations of unpublished writings by artists and designers. In 2020, they lunched an online subscription service called ‘The Generalist’. SPACE interviewed erosis, to explore the ways in which they are trying to expand this liminal space little by little, and how they view their subjects from both a broad perspective and with a more penetrating gaze.

interview Vince Ahn, Irene Yoo co-directors, erosis × Choi Eunhwa

Choi Eunhwa (Choi): I’m curious about your backgrounds. How did you come to open this studio together?

Vince Ahn (Ahn): I studied architecture at Cornell University and then worked in an architectural office. In the end, I got sidetracked. (laugh) I became interested in curation and so attended the relevant classes in my 4th and 5th years, and later I served as an assistant curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Irene Yoo (Yoo): I traveled back and forth between Korea and the U.S. I studied visual design at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. I began my career as an intern in an art gallery and later worked at an advertisement company. Afterwards, I came back to Korea and worked as a freelance designer across various fields. At that time, I came to know Vince Ahn who was living in my neighbourhood. We both had a thirst for trying something new. One day, Vince said to me, ‘there is no Korean translation of Adolf Loos’ writing about fashion. How about we try it together?’. That’s when I really embarked upon this collaborative enterprise.

Choi: You handle the entire process from planning, research, archiving, translation, editing, and production to publication. Why are you so hard on yourselves? (laugh)

Yoo: Guided by curiosity, I found this great text. As there was no translation of it, we considered what we could do in this field by ourselves. Also, we realised that we needed to develop an editing system that would deliver differently sourced texts with a consistent message and tone, and this was to be the same with our design and publication. All of our decisions were made out of necessity but with acute attention to detail.

Ahn: Because we participate in the entire working process, from planning to production, we are able to express our identity clearly and maintain a certain balance in each project.

ⓒSon Mihyun

Choi: What makes you different from other existing content producers on art and design?

Yoo: Content about a professional field targets a specific audience. Different content exists for professionals and nonprofessionals. What we are trying to do is to create a transitional zone in which we can fill the gap between them. erosis, the name of our studio, came from the Latin word ‘erodere’ meaning ‘to erode’. It reflects our vision of tearing down boundaries and creating this exciting liminal space. We want to erode the boundaries not only between professionals and non-professionals but also between different fields.

Choi: You often focus on a specific person. Is this one of the ways of eroding those boundaries?

Ahn: We wanted to appear more approachable from the beginning. No matter how difficult a topic is, it can sound more fun and accessible depending on the author. We thought readers would absorb new fields or subjects more easily if we overlaid our text with the image of a specific person.

Yoo: People understand the world and appreciate beauty in their own way. This personal system sometimes makes connections with a system of others. We wanted to introduce different ways of appreciating the beauty of the world by borrowing each individual’s unique lens through which to see the world.

Choi: Your first project Manuscripts is a compilation of unpublished writings by designers and artists. So far, Adolf Loos, Rainer Maria Rilke and Paola Antonelli have been covered as the main figure in each edition. How do you elect your main figure and excavate publishable content?

Ahn: Many come about by chance. We came to Adolf Loos in this way. One day, I went to a bookstore in Seattle, and the storekeeper told me that Adolf Loos wrote a number of columns and essays about fashion during his lifetime. I realised that these writings are rare items, so I began researching it out of curiosity. Just like that, we found clues in seemingly insignificant sources and put them together. It’s like gathering crumbs randomly scattered all around, and we feel a certain excitement at this stage. As for Manuscripts 02: Rainer Maria Rilke, the second is the series, we were working on Adolf Loos when we discovered that Rainer Maria Rilke lived in Vienna, Austria in the same period as him. That prompted us to dig up more about him, again out of curiosity. The beginning may always be different, but the initial spark of conversation always plays an important role. I also browse Instagram pages, chew things said to me in passing or carefully pick through a book’s footnotes written in tiny letters. I skim through news articles and view a wide variety of content on online channels such as Youtube and Podcasts as if riding the wave. The most important attribute required at this excavation stage is curiosity…but what’s even more important is tenacity.

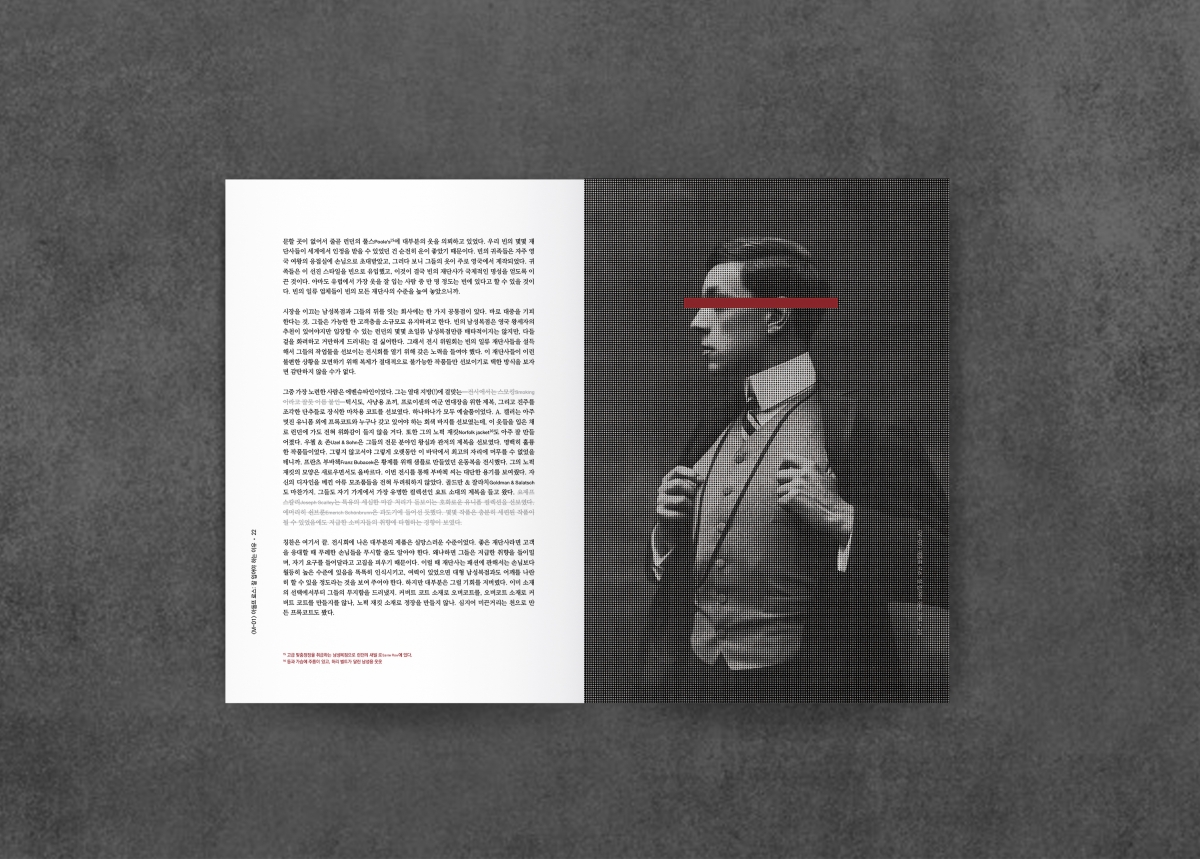

Choi: You collect various versions of the same manuscript, including first, second and further editions. You keep a detailed record of what had been erased, added or modified over many years, and make this process of emendation visible in your publication by using correction marks and different font colours.

Ahn: I realised that text is a flexible medium: if you look at writing’s production methods in reverse, you will know that writing, an action of integrity, goes through many revolutions and changes of mind. Adolf Loos modified his writings considering the fashion of the time and the media, but some aspects were left as they were. It was interesting to see that text is not as permanent as people think it might be. We decided to combine these different versions of a text into other new versions, rather than picking one among many. We expose what has been modified in the letters or by drawing a midline.

Choi: How do you obtain the copyright?

Ahn: It is not always the case but in most of countries copyright expires 70 years after the death of the author. We began this initiative out of pure curiosity, and we didn’t have any funds. (laugh) Therefore, for practical reasons we opted for old texts first.

Choi: Please tell me about your translation work. I know that you coordinate tone of voice, word order and rhythm to vividly and accurately express the character of your chosen figure. How does this process work in detail? And what do you care about most during that process?

Yoo: Adolf Loos had a quite straightforward personality. He used short sentences to clearly define his position and to express it in a plain way. He rarely used an interrogative expression but presented his opinion in a clear tone. For example, when he received bad feedback on his articles for newspapers, he would bring it up in his article the following week and refute such criticism word for word. He maintained such a strong attitude towards his writings throughout his lifetime.

Ahn: Alvar Alto, the main figure in our recent edition, however, is a bit trickier. We are looking at the essays, lectures and interviews that he produced over fifty years. His writings from his twenties are straightforward and aspirational, like Adolf Loos’s, however, in his thirties and forties this attitude gradually softened and gentler expressions began to emerge. Moreover, he used various languages, including Swedish, German and English, as occasion demanded. Solving such a complicated equation and reaching the heart of the message he wanted to deliver is a difficult task. Nevertheless, I found some coherent features. His writings are elegant and plain. It’s similar to his designs, which seek a balance between the poetic and practical. We are making every effort to put these characteristics into words.

Choi: The format of the Manuscripts is also very unique. Though it’s a paper book, the pages are not bound but fastened with a clip, and then placed into a translucent envelope.

Yoo: We used clips as binders so that we didn’t have to undergo a binding process, really in order to emphasise the characteristics of this modifiable or uncompleted text. Also, we make our readers take the book out of an envelope so that they can experience the moment of discovering unknown writing. Readers can change the order of the pages as they please, or they can fix one of them to their wall like a poster.

Choi: You have extended the concept of Manuscripts into your recently launched online subscription service ‘The Generalist’. These days, there are many different kinds of mailing services. You offer curated impression of something from the past, not only the present, and that makes your service different from the others. Is there any reason that you decided to change the format of your content?

Ahn: There are two reasons. First, in the Manuscripts, a publication series based on individuals, it is hard to introduce someone who has not written a bunch of articles or been interviewed. We thought a newsletter format might offer a new way. Second, it improves accessibility to our content. Manuscripts is an independent publication, so there are not many vendors for it. It is a handmade product, and each depends upon a time-consuming period of gestation and production. Also, it is relatively fragile due to its unique format. While seeking a solution by which we might solve these problems, we decided to digitise our content. We always try to turn lemons into lemonade! We thought we would be able to offer a wider range of services as it would become possible to cover other types of content, such as video or audio clips and external links which cannot be included in printed material. While ‘The Generalist’ is an exploration of an entire creative field, Manuscripts offers clarity of focus on a single person.

Choi: Is there any subscription service or platform that you find interesting?

Ahn: There is a platform called e-flux. It categorises its content as architecture, education and books, and under architecture, there are smaller categories such as housing, software, infrastructure, environment and inclusiveness. I was impressed by the way it narrates one story in a calm and orderly manner, rather than trying to quickly deliver latest news and trends like Dezeen or ArchDaily.

Yoo: I’m subscribe to quite a lot of services such as Youtube, Watcha, Spotify and ‘Daily Lee Sulla’.

Ahn: We often talk about the algorithm between us. Service providers using AI-based algorithms have a clear objective: they want their users to spend more time with their applications. To that end, they relentlessly recommend certain content similar to what the user has consumed in the recent past. We are on the opposite side. We guide our users to attend to what may not have taken their attention until now.

Yoo: It’s more convenient to use a service that knows about my taste. However, if every single one of them adotps the same direction, it becomes difficult to encounter new things.

Choi: Your newsletter service ‘The Generalist’ operates on a seasonal basis. It covered architecture as its main topic over three months, from the 6th of July to the 23rd of October. The newsletter is sent three or four times a week via email, and this will come to comprise a collection of about 50 letters under the theme of architecture. Please share the ways you approached architecture, such a vast field of study.

Ahn: The backbone of ‘The Generalist’ is the content of the ‘Manuscripts’. It explored the texts of the writings, lectures and speeches that Alvar Alto produced over 30 years. The first thing to do was to take a multi-faceted approach to the personality of Alvar Alto and, through that, to extract keywords. For example, he wrote an essay about the connections among sculpture, paintings and architecture, devising a discourse between ‘architecture and art’. We took that as a keyword and extended our broader content based on this conception. Then in the following newsletter, we introduced the texts of Do Ho Suh, who explores the connections between architecture and installation art, and of Maya Lin, who is well-known for her land art work and monumental projects. With ‘Manuscripts’ as the main plot, subplots like ‘Logs’, ‘The Bigger Picture’, ‘Lists’, ‘Perspectives’, and ‘Chapters’ come one after another in a flexible way. Considering the nature of a newsletter, we tried to make some of our content take the form of a series, but it’s no problem to read each part separately. It’s like when an exhibition is well-curated and you have a good experience if you appreciate the artworks in the prescribed order—but if you ignore the order and observe them in whichever order takes your fancy, then you still can find connections among them.

Choi: You excavate a wide range of content and introduce these little known ideas and themes to readers, without being limited by the time they were made or the medium in which they are contained. What overarching values does erosis pursue?

Ahn: As there are diverse channels for knowledge mining, we can explore texts that have been hidden somewhere in Europe, or an Instagram live stream that ended five minutes ago. However, we believe a meaningful message in a good text can have a significant impact on people beyond time and space. Especially, texts from the past often correspond to the rapidly changing trends of today and, through that, secure their relevance. Adolf Loos’ writing about women’s fashion also corresponds to today’s issues around feminism and touches people’s hearts. Above all else, however, these classic texts present a new perspective from which we can discover the beauty of this world, and that’s the key point. Particularly, in the early 20th century, discovering and protecting the beauty of the world became an important issue due to the rapid urban expansion, technological development and wars. And the traces left by artists who struggled with that remain intact in the texts written in that era.

Choi: Please share your opinion of the future of newsletter services, and please note your future plans for erosis.

Yoo: I’ve seen analysis of the life span of content, sorted by medium such as e-books, video-clips and social media. According to this analysis, content typically disappears within 18 minutes on Twitter, 5 hours on Facebook and 21 hours on Instagram, but newsletters remain valid for months. We wanted to deliver our content to readers at sufficiently long intervals, so we decided to start this newsletter service. One of the merits of newsletter is that it offers a rather personal experience. Unlike Youtube or Instagram, it doesn’t have a comment feature, and this helps you to explore your own thoughts without interruption.

Ahn: We have followed a ‘play it by ear’ attitude. We tend to give it a go rather than trying to speculate too much on what lies ahead. There are quite a number of things in the pipeline; we are planning to introduce Miniscripts, a smaller and lighter version of Manuscripts, and to continue to produce books that explore work by individuals that have not yet received sufficient illumination.

https://erosis.kr/

https://erosis.kr/