SOAP, a design studio founded by Kwon Soonyup and Chang Dongsun, oversees an architectural firm and an art gallery. Identifying the problems inherent to public art projects, two joint design organisations have suggested alternatives that will focus on a user’s spatial experience.

Interview Kwon Soonyup, Chang Dongsun x Kim Yeram

Kim Yeram (Kim): SOAP runs an architectural firm to conduct builing projects and the Museum SODA, which is dedicated to installations and exhibitions. You maintain a horizontal relationship between your two design teams. I would like to hear more about how you came to operate your design studio in this way.

Kwon Soonyup (Kwon): When I came back to Korea after finishing my study, I had concern about how best to organise my architectural firm. At that time I noticed that many architectural firms were under the control of one architect, particularly in terms of their design approach. It is often assumed that the privileging of a principal architect’s style makes it easier to build a house style and identity, but I think it this approach inevitably exhausts the inner resources of the architect. In the same way that a relationship respects individual personal abilities and opinions so that each party can be improved in some way, I decided to establish a studio that would place its emphasis on teamwork.

Chang Dongsun (Chang): Museum SODA is the renovation of a large uncompleted jjim-jil-bang (public bathhouse in Korea) as a cultural art facility. This museum, our first project, provided the opportunity to bring together experts from across various design genres. This is because the scope of work was too wide. While architectural projects usually develop designs after the use is decided, we were responsible for everything from deciding building programmes to establishing the operative direction of the museum. The situation was characterised by members of various fields, such as architecture, interior design, graphic design, and design management, putting their heads in order together to create results.

Kim: It seems interesting that the project which does not clearly distinguish between design and art, which has influenced the organisation of the studio members. Although people with a keen understanding of the two areas here gather under one roof, their working scope is clearly divided.

Chang: As our projects cover various fields, our members often play hybrid roles. As architectural projects require participation from divisions in planning, design, branding, and operation strategy, staff members from each field must have a good grasp of the language of other field. While they are able to interpret one other’s intentions, they may overstep into the expertise of the other field. To prevent this situation from occurring, we keep discussion open to the extent of mentioning concerns from the perspective of one’s field instead of pointing out any personal objections. I think internal conversations are a useful tool to explain design intentions fully to those outside the studio. Experts in management and planning must give an architect’s opinions to project stakeholders, and designers must be able to reflect the future direction for spatial programmes in their design work.

Kwon: Interestingly, people in my studio interpret the same logo in different ways. Architects might read it as a mass or a drawing, while graphic designers interpret it as a pattern to apply to their own ends. Various perspectives can be created in an environment where one can comfortably express one’s own views, and they inspire and provide a stimulus to collaborators. I don’t confine problem-solving methods to architecture, because I don’t think we can’t get good results if we just fit other elements into the bigger picture offered by an architect.

Museum SODA (Image courtesy of SOAP)

Hwaseong 3.1 Independence Movement Memorial Centre

Water Walk

Kim: Since you completed Museum SODA, you have participated in many public art projects. For the Hwaseong 3.1 Independence Movement Memorial Centre (2019), you drew traces from the road delineating the spirit of the independence movement into a disused public health centre, and you extended the island’s Dulle-gil road to the sea at Water Walk (2018) on Jebudo Island. Based on the design intentions of these two projects, please tell me more about the architectural values pursued at SOAP.

Kwon: I think that it is the significance of the experience of a place rather than the beauty of a building that is of importance to us; this is a long-held belief in our studio. While avoiding excessive amounts of design compared to those encountered in the surrounding environment, I hope that our buildings will not simply blur into the landscape. As such, we are making every effort to coordinate the extent to which our buildings will stand out from its surrounding landscape. The Hwaseong 3.1 Independence Movement Memorial Centre stands at the entrance to a 31km-long road. In this project, we placed greater emphasis on architecture rather than on the landscape, encouraging people to walk along the road. Leaving only the structure of the disused public health centre, we planned an exhibition space that would explain the independence movement, offering a memorial space for the victims and a rest area where people can take a pause in the forest. The project began simply as a rest area, but we were able to add an exhibition space to the building as we felt strongly that the meaning of the surrounding landscape had to be explained to people before they walk along the road. The design of the Water Walk on Jebudo Island was originally prompted by the requirement that we build a boat-shaped pavilion. The client was more insistent about the building’s shape than its purpose. We suggested that the building could focus on the experience of watching the ebb and flow of the tide, while nearly at the sea level, instead of adopting the simple boat shape. Fortunately, the client accepted our proposal and we had the opportunity to create a horizontal viewing platform.

Kim: It is interesting that in most of your public art projects you have proposed new alternatives as opposed to following an original plan. I heard that you also proposed a masterplan for the Jebudo Island Culture and Arts Island project (2015), including Water Walk.

Chang: Jebudo Island is one of the premier tourist destinations on the west coast, but it was full of with illegal buildings for touting, ruining the environment on the island and drastically decreasing the number of visitors. Hwaseong City commissioned the project with the simple idea that it could reverse the situation by constructing a nice pavilion from which to take photos. Regarding this as the wrong solution for a fundamental problem faced by the island, we asked for some time to think about it. After conducting sufficient internal discussions, we proposed a project for the Culture and Arts Island that was guided by the aim of restoring the natural environment in stages. In the first stage, we planned to unify the visual identity of the key elements of the island, and to construct ‘Art Park’, a container-type exhibition space. Then, we tried to create several observation points from which to appreciate wider nature by following the perimeter of the island.

Kim: When you were implementing your masterplan, the sites for these view points had not yet been determined. What were the criteria you adopted to select the most appropriate locations for buildings, and what experience did you intend to provide on these sites?

Kwon: We have often been commissioned for public projects that have not yet fully confirmed their sites. The situation that forces an architect to select a site is like examining one’s pulse. It is extremely difficult to diagnose the specific function and shape of a building that will be able to activate a space or in this case an island. First, we demolished the existing poorly maintained facilities to restore the original appearance of the island. After clearing the island, we planned several observation points along the 830m-long road, but we could only install some facilities due to our limited budget (laugh). The observation facilities were placed at points at which people could enjoy dramatic weather changes, tides, and sunset on Jebudo Island.

Kim: The design principles adopted to organise the island’s wider environment remind me of the Gapado project designed by ONE O ONE architects.

Chang: The two projects aimed to revive islands damaged by excessive tourism. The problems faced by such islands cannot be solved by improving only certain elements, as all elements are organically connected by scenic and economic relations. Both Jebudo island and Gapado island tried to improve the island environment through cultural and art programs and pursued various approaches to solving the problem. However, I think the process of presenting design solutions is different. For our Culture and Arts Island project, we had to spend two and a half years persuading a lot of local stakeholders. Since we, and not local government, originally proposed the project, we had to conduct regular evaluations of its performance. As we were not allowed to carry out the project in the following quarter if we hadn’t achieved tangible results, we gradually carried out small-scale works in accordance with the budget.

Kim: Gungpyeong Art Pavilion OSOL (2019) is a public art project located between Gyeonggi Bay and a 100-year-old pine forest. The pavilion design seems to reflect the shape of pine trees, with long, thin joints, and the way in which the sea reflects sunlight.

Chang: OSOL and its site belong to the city, a well preserved environment due to the delayed development project of neighbouring tourist attractions. City authorities wanted to demolish the container office that was responsible for the coastal promenade and to replace it with an observation deck. However, it was evident that such construction would adversely affect the weak-rooted trees. We persuaded the client that the experience of wandering beneath a long stretch of pine trees lining the coast was more important than providing a view through a structure.

Kwon: The fact that pine trees meet the sea is what makes this place attractive. Pine needles resemble the waves of the sea, but their colours are completely different. To naturally place the pavilion between this green and blue, we tried to create a terrain of an ambiguous boundary line by applying a medium tone colouring. Instead of artificially imitating natural colors, we used reflective aluminum to make the pavilion change its colour according to its surroundings.

Kim: Anodized aluminum is difficult to work with on the construction site as it is covered in a film. Why did you opt to use this material?

Kwon: Anodized aluminum can be bent before coating, but it cannot be deformed once it is coated. It is also difficult to weld even when using accessory materials, so the assembly method should be considered from an early point in the design stage. To use this material in a large installation work is inconvenient as it must be divided into parts that can fit into a kiln. However, accurate calculation of the material assembly will make the resulting construction appear to be a single piece. Another advantage of anodized aluminum is that there is less risk of corrosion and damage compared to other materials.

Gungpyeong Art Pavilion OSOL

Gungpyeong Art Pavilion OSOL

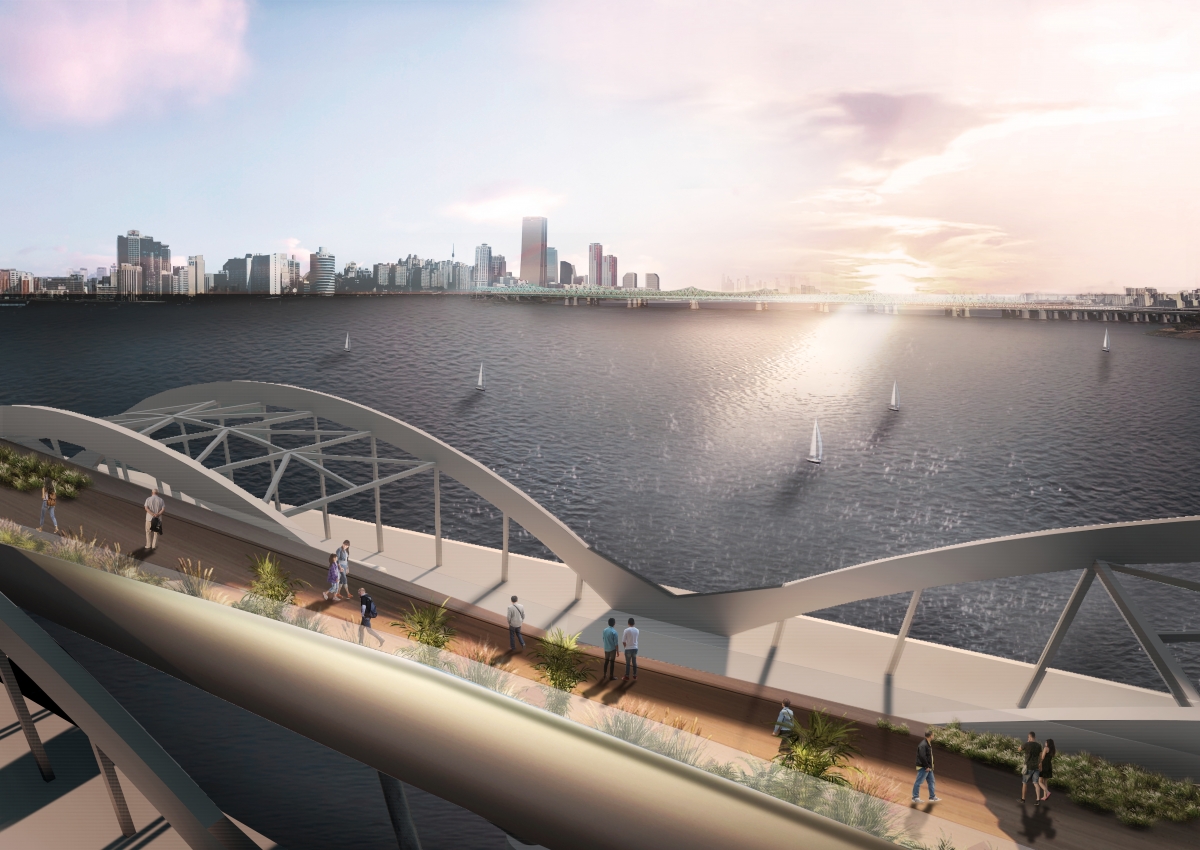

Hangang Sky Walkway (will be opened in 2022 / Image courtesy of SOAP)

Hangang Sky Walkway (will be opened in 2022 / Image courtesy of SOAP)

Kim: Recently, you won the Hangang Sky Walkway Design Competition and the commission to design a public walkway over the Hangang Bridge. What kind of viewscape design did you hope to realise between the Han River, a landscape representative of Seoul’s natural beauty, and the Hangang Bridge, the artificial hallmark that crosses it?

Kwon: The competition required us to consider the Han River, an important urban focal point in Seoul, and the Hangang Bridge as influenced by the river. There are many bridges connecting the north and south of the Han River, but I don't think they always provide a good context or experience for crossing the river. Reflective Scape is a proposal that interprets the historical events of King Jeongjo, who crossed the Han River using a boat bridge in the Joseon Dynasty. We used a boat with a gentle curve for our design motif informing the walkway, and we placed benches and various facilities on the 10.5m-wide and 500m-long public pedestrian walkway to allow people to look around and take a break.

Chang: This project is a symbol that expresses what we have sensed in an intensive form. We have carried out a lot of small scale works, and I think that our portfolio of work has led to a design that enriches our experience.

Kim: There are many factors to consider, such as the Han River, Hangang Bridge, and Nodeul Island. What aspects of the scenery you wanted to highlight to visitors and what did you have to hide on the walkway?

Kwon: The Hangang Bridge, so familiar to the citizens of Seoul, may be read as another landscape entirely when combined with the Sky Walkway. We designed the landscape to focus on this new experience. We designed a walkway in a wave shape to make it form an organic relationship with the existing bridge when viewed from a distance. The arched Hangang Bridge obstructs the view of pedestrians in some sections, and we planned some scenic planting to hide the fundamental structure. At the lower level of the walkway, we planned a terrace from which to enjoy a wide view of the Han River.Kim: In addition to the Hangang Sky Walkway, you are also working on the second-stage of Seoullo 7017, and a space designed for the younger generations in the Sejong City Library. How do you expect the increasing number of urban environment projects to affect the architectural landscape pursued by SOAP’s future design ambitions?

Kwon: Seoullo 7017 is about to embark upon the renovation of the surrounding area by revitalising the seven connecting roads. We won the branding competition for its signage, but we are going to propose some additional facilities such as a walking environment to provide places to stay. It feels similar to Jebudo Art Island Project in that it tries to link spaces by connecting the dots, but there are more things to think about as the project site is also adjacent to residential units. Chang: Carrying out urban projects made me pay more attention to apartment houses. I often think about where to live in order to maintain a proper distance between work and residence, and about the most effective floor plans for a residential unit. I am motivated by the desire to share these concerns with the many people which which I work on apartment house projects. Fortunately, we have Museum SODA, which provides us with the space to experiment with such ideas on a smaller scale. In the future, I would like to expand the scope of our studio by communicating SOAP’s interests to people through exhibitions, pavilions, and other related programmes.

Kwon Soonyup, Chang Dongsun

Kwon Soonyup received a Master of Architecture degree from Havard University and Bachelor’s degree from Inha University. After working for the New York and Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings, & Merril LLP, he established his own practice in Boston and expanded the practice in Seoul for the multidisciplinary design approach. He also has served as a design director of Museum SODA, experimenting the cultural boundary of design.

Chang Dongsun received MBA and specialized in Entrepreneurship and Strategy from Boson University. As a Design strategist, Hustler, Marketer and Entrepreneur, She has experienced in IT and Design start-ups in US. She also founded Museum SODA, in Korea and works as a Business Director.

Chang Dongsun received MBA and specialized in Entrepreneurship and Strategy from Boson University. As a Design strategist, Hustler, Marketer and Entrepreneur, She has experienced in IT and Design start-ups in US. She also founded Museum SODA, in Korea and works as a Business Director.

56