There has been a growing trend in recent few years of work geared towards the tween generation. The late 2000s saw the growth of spaces dedicated to children, mainly in the form of museums and art galleries, culminating in 2017 with a movement to enhance environments for children under the Seoul Metropolitan Government¡¯s Dream Class Project. Similar initiatives followed in the private sphere. Save the Children Korea sought to improve urban playgrounds by remodeling Jungnang-gu¡¯s Sangbong Children¡¯s Park and Sehwa Children¡¯s Park, while ChildFund Korea launched a programme to enable children¡¯s free participation in its libraries and book cafés.

This cultural consensus to generate areas for the younger generation has led architects to participate in creating new design and education programmes. OOZOORO 1216, a library for the tween generation and the focus of this article, is one such example. A tweenager¡¯ is a neologism that amalgamates ¡®teenager¡¯ and ¡®between¡¯, to denote preteen and teenage adolescents in upper levels of elementary school to middle school. The project was conducted not through the conventional bidding system, but as a private-public partnership. The city government of Jeonju provided the physical space, while the Book Culture Foundation supplied funding, and the venture philanthropy fund, C Program, helped to organise a coherent effort. C Program invited experts from various fields, and charged Suh Min W. and Ji Jungwoo with design of the library. Suh and Ji have various architectural experiences such as the exhibition at the Children¡¯s Museum in the War Memorial of Korea, and the Seoul Animation Center. How did they conceive their creative direction for OOZOORO 1216?

A Library Created Through Children¡¯s Participation

Kim Yeram (Kim) The US and Europe differentiates tweenagers from teenagers and treats them independently as an age group. What is the approach in Korea?

Ji Jungwoo (Ji) Each country has its own social and educational systems, and the definition of a tweenager varies from state to state. The US refers to tweenagers as children of ages nine to thirteen, whereas Korea treats them as adolescents between the ages of twelve to sixteen.

Suh Min W. (Suh) The anglosphere has a separate terminology for describing teenagers; we do not. We refer to them as merely youths. Those of us who participated in OOZOORO 1216 chose to define tweenagers as adolescents aged twelve to sixteen who are undergoing a changing curriculum, and set out to design a space to meet their needs. The IDEA Group communications Co., Ltd. surveyed a sample of tweenagers to understand what they wanted, and GingerTproject set guiding principles for the project¡¯s management and workers. The youngest children in our target group are fourth and fifth graders in elementary school, who are beginning to discover their identities and feel the academic pressure to succeed. When we listened to their stories, we found that they did not feel their homes were sufficiently enriching spaces, in that they were not able to fully explore their potential in their surrounding environments. We hope that at the very least, third spaces such as libraries and playgrounds can offer them varied opportunities to do just that. So when we host design workshops, we ask them not ¡®what do you want¡¯, but ¡®tell us what you don¡¯t know and we¡¯ll search for answers to those questions together¡¯.

Kim The project involved the input of not only experts, but students of surrounding schools. How did that communication play out?

Ji Participatory design sounds like a novel concept, but any architect knows that good design is predicated on the communication of clients¡¯ needs. We ask clients to answer some of our prompts in writing, and help them to develop their ideas, and did the same in this project. Though many may assume that children will have simplistic needs and think of the space as merely one for play, in fact, they applied themselves as seriously and constructively as any expert. I thought this showed how the participatory design process could function as an activity that can more fully realise their potential than any class offered in school or private academies.

Suh The design process was a time for them to examine different ways of looking at the world.

Kim How does the project reflect the ideas generated by the kids during the participatory process?

Suh It¡¯s not as simple as their demanding ¡®we want this here¡¯ and our response, ¡®ok, we¡¯ll do that¡¯. Children have their own frame of experience and reference, so the way they communicate is highly instinctual. There¡¯s a need for us parse out what they mean and guide them step-by-step.

Kim Is there an overarching design concept for OOZOORO 1216?

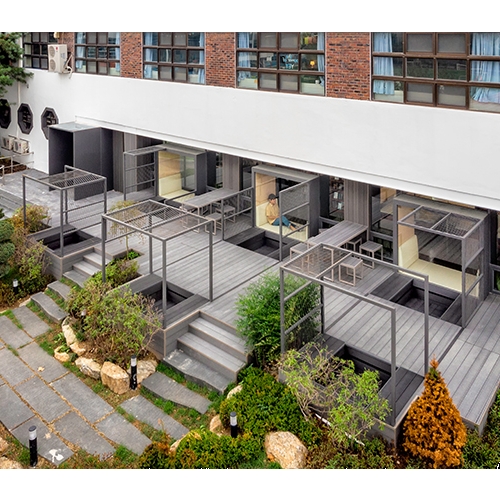

Ji From the get-go, we decided to veer away from the design of commercial facilities such as a DVD room, or karaoke booth, towards separate rooms. We wanted to create the library not as a haphazard collection of independent spaces, but as four areas connected by a road topped with a gable-shaped structure that successively leads to increasing levels of activity. This

intuitive organisation helps kids to plan their routes throughout the library, meaning areas in which circulation overlaps become spaces of their own.

Kim I wonder if administrators and librarians in this type of an environment might not be perceived as interferences by tweenage users. How did you physically separate the kids from the adults?

Ji For adults to act as helpers only, it was important that they be few and unobtrusive. We placed two facilities, an information desk and work station at two ends of the library, for them to be in clear view and easily accessible for kids whenever they needed.

Kim The blueprint and pictures give the impression of a densely populated environment with lots of furniture and facilities.

Ji Personally, I think rather than density an ¡®energy level¡¯ better encapsulates the library¡¯s layout. Kids of this age group are spirited to say the least, and we took care to provide a space that would be able to handle their vigour. We designed for group activities to occur near sloped areas, the multipurpose stairway and the central corridor, and individual activities to take place near the attic and the space below it.

Suh As OOZOORO 1216 is used first and foremost for children, we focused on energy levels as an important guiding principle for our design. And even though we have tried to account for what we think might be possible, the thing with kids is they will always surprise you. Case in point, we had a kid who read a book while hanging from a pipe on the ceiling.

Kim Speaking of kids and their unpredictability, this can lead to opportunities to find alternative uses for existing spaces, but also cause concerns for safety. Was any of this relevant at OOZOORO 1216?

Ji There is a storage room hidden behind a bookcase next to the librarian¡¯s corner. During the participatory design phase, there were some suggestions made that we should create a secret space, which resulted in the swinging bookshelf and the creation of a fun hideaway.

Suh If you tried to install a facility like that in an elementary school classroom, teachers would raise uniform concerns about safety and ask that the plan be scrapped, even though kids would love a hidden place like this. Not to mention that there are rigid regulations regarding safety that also act as hurdles, which stipulate that only rubber, plastic and composite wood be used as ingredients. So the result is that most spaces look the same in size and quality.

Kim Even though there are realistic limitations, you continue to create such play spaces. What is the most important thing that EUS+ Architects considers in designing facilities for play?

Ji That they be multipurpose. We make a lot of multipurpose framed structures that can fit whatever the user creates, because there are many ways in which users can fill a space out through their experiences, and through various programmes. Right now, most play spaces for children are a hodgepodge of manufactured goods. We want to create an alternative where they are filled with playscapes that capture various children¡¯s activities.

Kim Do you have any other plans for tweenagers in the works?

Ji The Book Culture Foundation and Seeart, two groups that were also part of the OOZOORO 1216 project, were involved in designing the Miracle Library that was featured ¡®Exclamation Mark—Let¡¯s Read Books!¡¯ on MBC. These days, we¡¯re working with them on a library in Gongneung-dong, Seoul that is the next step in this series. Our goal is to foster consensus regarding the need for the creation of a manual detailing spaces according to their different types, so that our experience can serve as a blueprint for similar projects across the country.

WOOZOORO 1216 <¤±¤± Workshop> ¨Ï Promotion Team for SPACE T + HyeondongJu

Graduate School after gaining practical experience at SAC International Ltd. He worked at Perkins Eastman designing

large-scale housing development, high-rise mixed-use apartments, and commercial facilities. He is interested in culture and art spaces such as museums, galleries, and sculpture parks, writes on relevant topics. He is currently involved in various projects related to children.

Ji Jungwoo studied architecture at Korea University and Cornell University Graduate School. He was research director

at JAD, and worked at Perkins Eastman and Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn Architects. He has been planning and researching architecture projects related to playgrounds and children for many years, and works at the forefront of work

designed for the younger generation in Korea and the US.