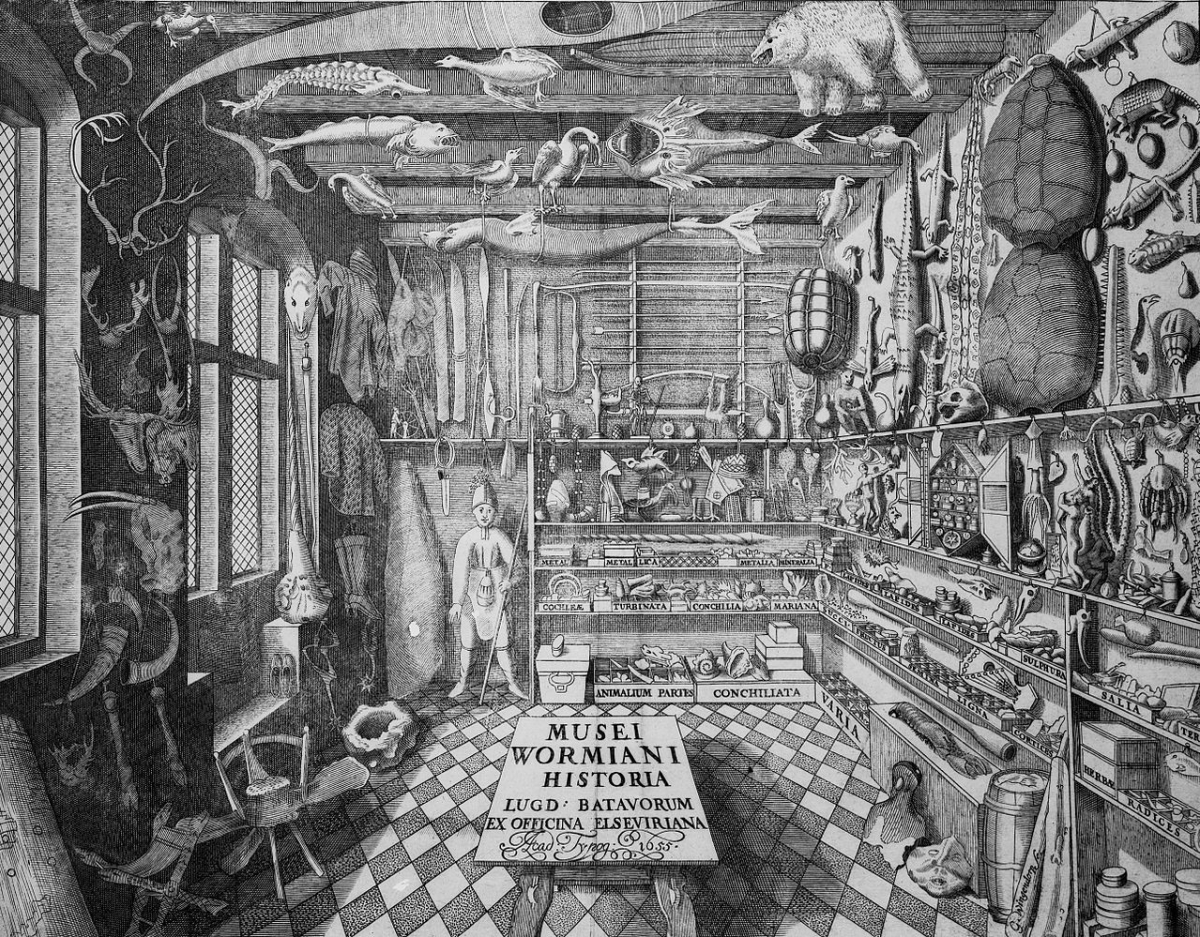

In ancient Egypt of 3rd century BC, a facility was built which functioned as a library, a research institute, and a place for meditation, known as the ‘Museion’.▼1 Museion, which is described as the first museum, has since then evolved into a Studiolo or a Cabinet of Curiosities, which was a place in which various objets were collected and assembled for study by the elite, before it finally evolving into the modern museum of today. This Cabinet of Curiosities where artworks and objects that were favoured by the royalty and aristocracy were collected together for view and study and protected from damage, was first opened for public access after the French Revolution in 1793 at the Louvre Museum. The motive behind the Louvre Museum’s establishment, to share the ideals of a modern nation and culture as a public property, is also reflected in the identities of numerous museums today.

Recently, a Cabinet of Curiosities opened in Cheongju, Korea. About 11,000 collected artworks from the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) were put on display at a tobacco processing plant in Cheongju, which had closed down in 2004. The MMCA Cheongju, which opened its doors as a ‘visible museum’ with the mission of ‘sharing public property’, provides the opportunity to enjoy cultural arts in a non-capital region by being located in a place which is not within the vicinities of Seoul. It is being highlighted for its potential to grow into the fourth branch building of the MMCA. Since its introduction, the art museum has continued to evolve in various ways by incorporating generational, regional, and aesthetic changes in perspectives, and the Cheongju branch is at the peak of this evolutionary cycle as it reflects the paradigms and trends of the 21st century art museum that are distinguishable from other art museums in Korea.

The Art Museums of Today: What Do They Live For?

With the expansion of the social influence of art museums, Eilean Hooper-Greenhill has developed critical reflections and a new paradigm regarding art museums since the 20th century under the concept of the ‘post museum’. According to her, a 21st century art museum expands upon the limitations of an art museum not only through evoking memories, feelings, conversations, discussions, and debates via artworks but also through active communication with its viewers. This has led to cafeterias, bookstores, art shops and other public facilities to find their place in museums, along with concerts, dance performances, film screenings, public lectures, and other various cultural activities, turning the museum into a multi-purpose cultural space. This was also accompanied by the commercial expansion of museum activities from familiar areas such as exhibitions, research, and education to marketing, management, and business. Furthermore, with the onset of the information age, various multimedia and tech-based tools and equipment have been brought in for the more effective management of the museum,▼2 and professionals such as educators (besides curators), registrars, exhibition display designers, archivists, conservators, and exhibition technicians have been recruited.

Such changes signal a paradigm shift in art museums. In other words, ‘it led to a transition from material to experience, from conservation-focus to educationfocus, from enlightenment to edutainment (both education and entertainment), from supplier-focus to user-focus, from statefocus to region-focus, from standardisation to specialisation, from offline to online integration, from bureaucratism to business rationalism, from curatorial organisation-focus to professional-focus, and from sedimentation of memories to creation of the future.’▼3 It is significant that the motif of these functional and organisational changes aligns itself to the actual functioning agents of the art museum - i.e., the ‘visitors’ and ‘professionals’. This also proves that the essential functions of the art museum - i.e., its professionalisation and popularisation - are being handled in a balanced way.

In her book, New Museum Theory and Practice, Janet Marstine argues that such points of change in society and consciousness overlap one another, and divided the art museum into four types: i.e. the shrine, the market-driven industry, colonising space, and the post-museum.▼4 In reality, these forms appear in an interrelated way, and this is especially the case of a contemporary art museum which exists as a complex mashup of perspectives between a classic and traditional shrine, a post-industrial marketdriven industry, a colonial perspective, and the post-museum perspective of a postsystem deterritorialisation. Today, when the post-museum feature is becoming more distinct, art museums are studying options from multiple angles on how to show consideration for their visitors and to expand their programme. The museum that is most forward thinking, and could act as a new art museum model, might be the MMCA. In that sense, it may be said that the Cheongju branch, which divides the function of a storage into that of exhibition and preservation, distinguishes itself by positioning the visitors and professionals at its centre is the result of a deep contemplation.

Frontispiece of Musei Wormiani Historia, depicting Ole Worm’s Cabinet of Curiosities

The Transformation of a Tobacco Plant: Alchemy of an Art Museum?

The tobacco processing plant taken over by MMCA Cheongju was ruled over by pigeons until Jan. 2011, since its closure in 2000. What triggered its cultural transformation was the moment it was selected as an exhibition space for the 2011 Cheongju Crafts Biennale. The decision made by Han Beomdeok, who was the Mayor of Cheongju back then (and still the current Mayor), to listen and respect the opinions of professionals including Chung Joonmo (director at 2011 Cheongju Crafts Biennale) on how to carry out the project, must be remembered as a special moment. This decision made in 2011 which became the cornerstone for MMCA Cheongju.

The abandoned factory that was left unoccupied for such a long time was dark to the point of requiring a flashlight to navigate, and it seemed too dangerous for entry. However, there was no doubt that this building was special as it embodied ‘modernity’. While the grid system, which appeared in the works of Le Corbusier, Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, Sol LeWitt, and Donald Judd, overlapped with the European art museum spaces that were already practicing spatialisation of cultural facilities using abandoned locations, the potential of this building to be transformed into a cultural base appeared reasonable.

Finally, in 2018, the MMCA Cheongju opened its doors. The remodeling work of Cheongju Crafts Biennale hall, which is operated by the local government, is also on the way. The Cheongju branch project began from 2012, but the given time was not generous. There were the two major aspects, which needed enough time to do, behind the realization of the Cheongju branch: the construction of the remodeling process, and the integration between securement and management of the distinguishable features of its branch. This may be because of the differences between the estimated time at the administrative level and the actual time used to carry out the task, which is a common issue arising in central government as well as in regional autonomous governments. Also, the habitual lack of interest towards a software expansion for the sake of focusing time and budget on hardware establishment must also have been part of the reason.

Moreover, as the software of the MMCA Cheongju branch achieves a unique identity as a space where the collected items are revealed, questions such as how these collected items will be stored, managed, researched, and be taught to others will follow. Consequently, the storage policy of the MMCA, the development of its direction regarding storage, as well as the current classification of the stored artworks, are tasks that must be carried out to establish a base upon which research work regarding key artworks of the museum, museum’s core themes and artists, and independent education programmes must be built. This will allow for future reorientation of policies regarding the collections as well as international branding and marketing. In this sense, a medium to long-term visionfor Cheongju branch should be put in place and be enacted, but unfortunately, it seems that there are no such plans yet.

The Museum of Anthropology at University of British Columbia, which opened in 1976, is well-known as an art museum in the form of a storage facility alongside the Schaulager in Switzerland. Other than its function of preserving artworks and relics, this exhibition/ storage art museum also carries out its role through exhibitions, education, providing information, and sharing experiences with its visitors. As a ‘visible museum’, the Cheongju branch must also make sure that exhibition is delicately connected to its relevant functions. There are always interesting new ideas for putting on educational programmes. Examples such as the drawing programme at the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands, the ceramic gallery workshop at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the various workshops and discussions geared towards a young audience in Tate Britain are all cases that have managed to intimately connect and reinforce the intrinsic functions of the art museum with education. This will require time for contemplation, but it must be stated beforehand that this must also show connection with the unique feature of the Cheongju branch. As a feature that was highlighted at the museum’s opening, the Conservation Science Laboratory needs to be improved in that it should not simply be posting information but also organising special programmes for the general public and professionals. While there may be instances when the work of the Conservation Science Laboratory needs to be done privately, according to the state of the artwork and the method of conservation, the potential behind conservation science to create new content by integrating art and scientific technology is significant.

There is no debate over the main characteristic of the Cheongju branch as a ‘visible museum’. Despite the fact that its space is built upon the remodeled structure of the original tobacco processing plant, there is still the need to be concerned about its basic functional space arrangements in terms of exhibition, guide, information, education, resting area, and the traffic lines in the storage exhibition. The lobby that is often overly populated by visitors, and the exhibition spaces where the traffic lines for the collections and the visitors dangerously clash, need to be improved. There is also a need to reorganise the spaces shared between the nearby biennale hall and the visitor’s traffic line that extends all the way from the lobby to the 5th floor. The biggest concern is that the exhibition of artworks might compromise the safety of the artworks, due to the lack of secure distance between the artwork and the visitor. Despite the inconvenience, a bag search must be carried out, and it is also necessary to have the visitors go through air cleaning equipment before entering the storage exhibition area. Other than the special exhibition halls, there is also a need to look for a method to limit the opening hours and the number of visitors entering the storage exhibition space.

MMCA Cheongju: Going Beyond the Cabinet of Curiosities

The spatialisation of an idle space in an art museum does not happen spontaneously but require very detailed strategic planning. There is a tendency among Korean public organisations to be stingy with the time allocated for contemplation and planning. Upon looking at the spatial composition of the Cheongju branch, it seems that the emphasis is on artwork storage and conservation science. In contrast to the ideas that they have put forth, such as ‘visible storage’, the management of the exhibition’s education programme, and the cradle of artwork conservation science, it seems that the stress is mostly placed on the opening of the Cabinet of Curiosities. It appears that it will take some time before the visible conservation science room and the Larchiveum are fully open for access, and the education programme will also require a special accompanying plan. The problem, however, is that such improvement work will no doubt be affected by the work that is piling up within the museum itself. The exhibition planning of the MMCA’s four branches is currently being managed by one chief curator, resulting ineffective administration, and the post of director of the MMCA is still left empty.

The MMCA has steadily grown into a representative contemporary art platform in Asia and as a cradle for Korean contemporary art since opening in 1969. Regardless, however, of how it is able to secure a special space for the reinforcement of contemporaneity and expandability of Korean art, and to allow Korean art to compete at the international level, much work has to be done along multiple lines. The task of strategically branding the value of the collections in the MMCA is crucial, and the Cheongju branch can become bedrock to the creation of this opportunity. Planning a collection exhibition on the basis of the placeness that embodies the memory and the aura of the industrial age, or connecting the permanent storage exhibition hall with a stage for discussion, may be some of the means of accomplishing this. However, this is not about burying oneself in the past or memory. The intention is to not forget the potential for change or the origin of such dynamism, but it is unfortunate that the history and memory of the location as a tobacco processing plant has simply been reduced to a single photo hung on a wall in the museum lobby. It is hoped that the tobacco processing plant / art museum will expand beyond the Cabinet of Curiosities to become a ‘visible stage for contemporary art’.

1. Chun Jinsung, History · Civilizations, (Salim, 2004), p. 12.

2. A. Mintz, ‘Media and museums: A museum perspective’, In S. Thomas, & A. Mintz (eds.), The Virtual and the Real : Media in the Museum (Washington D.C.: American Association of Museums, 1998).

3. Yang Hyun-Mee et al., ‘A Study on Middle and Long-term Improvement Methods for Museums and Art Museums’ (Korea

Culture & Tourism Institute, 2002), p. 14.

4. Janet Marstine, ‘Introduction’, in New Museum Theory and Practice, ed. Janet Marstine (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006), pp. 8 – 21.