SPACE December 2025 (No. 697)

‘Cross Critique’ was conceived to examine two projects under a related theme. It aims to serve as a space for critical dialogue between architects, where discussions can reveal the pressing issues and key topics in contemporary architectural practice.

From accusations of political collusion to sweeping interpretations of modernism, Thomas Heatherwick (director, Heatherwick Studio; hereinafter Heatherwick) has long courted controversy. Under his direction, the Thematic Exhibition of the 5th Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (covered in SPACE No. 696) has once again fueled debate. At the entrance to Songhyeon Green Plaza, he installed his ‘Humanise Wall’ on an overwhelming scale, while the twenty-four ‘Walls of Public Life’ placed opposite it were at more than one-hundredth of its size. According to Heatherwick, the three-dimensional elevations on view here stand in contrast to the ‘boring’ work of Le Corbusier. Against this backdrop, we speak with Chung Isak (professor, Dongyang University), who participated as an exhibiting artist, and Chon Jaewoo (principal, HYPERSPANDREL), who adapted the theme and form of the Walls of Public Life to develop the ‘K-Wall Challenge’ on Instagram. Here, there is criticism, affirmation, jealousy, and humour.

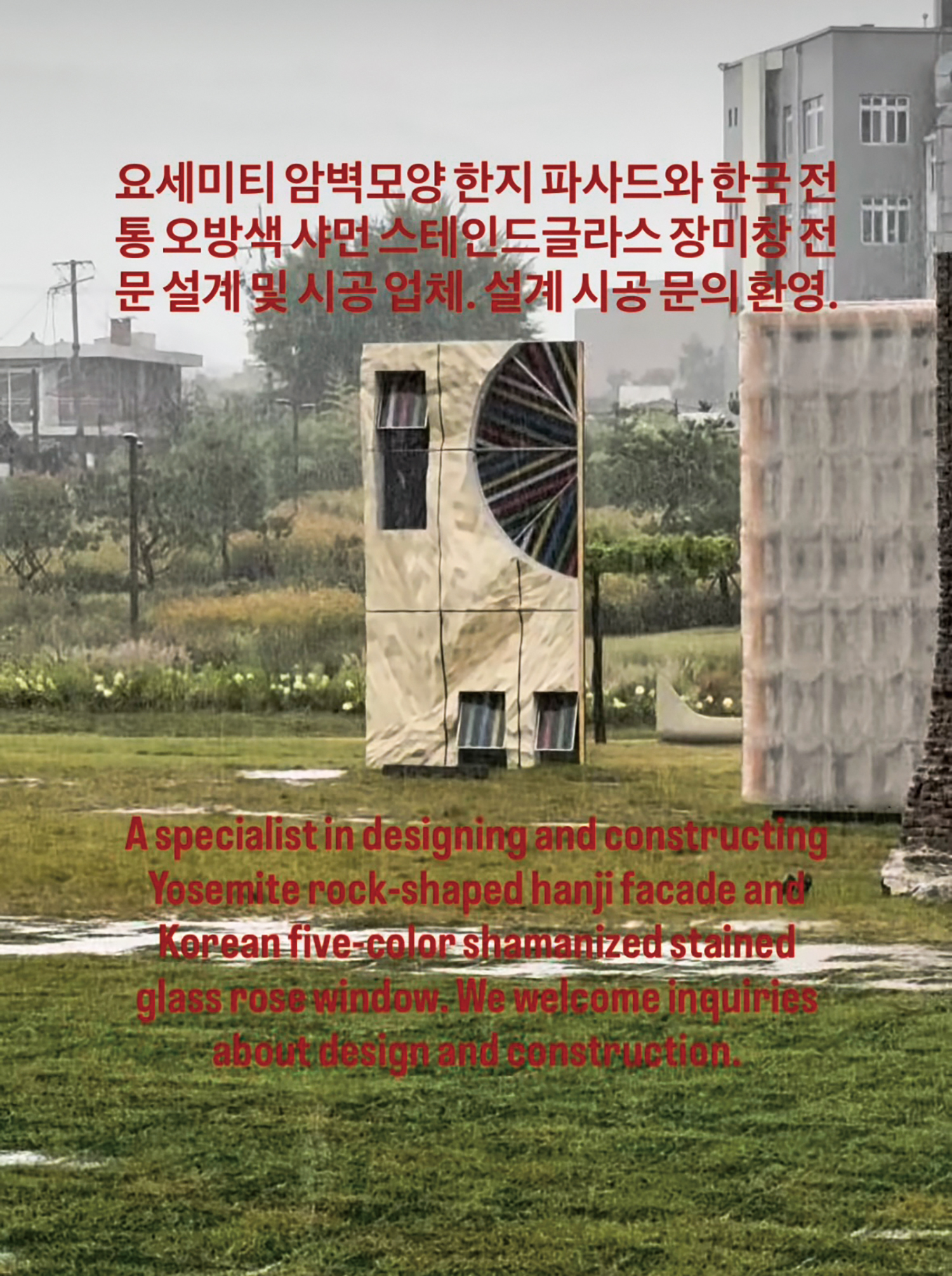

Residual Heritage (2025)

Image and text of Residual Heritage uploaded by Chung Isak ©Chung Isak

The Theme, Format, and Purpose of the Thematic Exhibition

Park Jiyoun (Park): First, tell us how you came to participate in the ‘Walls of Public Life’ project and what led you to initiate the ‘K-Wall Challenge’.

Chung Isak (Chung): The Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) informed us that twenty-four architects and professionals from other fields would take part in creating Walls of Public Life, with five Korean architect teams among them, and that our office, a.co.lab architects, had been selected. But once involved, Heatherwick issued far more additional guidelines than expected. For instance, the wall could not be transparent, and if a window was created, it had to be made entirely of reflective acrylic. The key was to direct attention not toward the spatial concept of a pavilion but toward the building’s elevation—its skin. Later, when I saw the other installations, some had swings, and some could even be entered. Given the artists’ persistence and the time constraints, I imagine it would have been difficult for the director to maintain total control.

Chon Jaewoo (Chon): I had participated in the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism twice before and reviewed the open calls every year. When I saw the guidelines related to the ‘Humanise Wall’ this time, Heatherwick was recruiting contributors whose work would be incorporated into his large-scale installation. It felt like a supporting role and I did not think it would benefit my portfolio, so I chose not to apply.

Chung: As Chon mentioned, Heatherwick clearly had a specific picture in mind and sought people who would complete it—like assembling a puzzle. While many biennales allow artists to reveal their individual character under a shared theme, this one seemed focused on how effectively a unified message could be articulated.

Chon: I did not resonate with that format, so although no one would have noticed, I was quietly boycotting it! (laugh) Even before the Biennale results were announced, criticism had already been directed at Heatherwick. As a foreign architect whose architectural agenda has also been criticised in the U.K., he was an easy target. My intention was not to criticise; I simply felt that Heatherwick’s logic – ‘architecture is boring unless it is beautiful’ – was something even I could comment on. Since humour and wit are central to my practice, I thought the K-Wall Challenge on Instagram would be fun. In truth, the project emerged from complex emotions. Heatherwick’s completed Humanise Wall, and the way it overwhelmed the Walls of Public Life, felt bizarre, yet at the same time, I felt a kind of jealousy, a desire to participate in the Walls of Public Life myself. The participants of the K-Wall Challenge are those who were not invited to the Biennale, and I imagine they, too, wondered what kind of wall they would have created had they been selected, even while criticising it. In that sense, the project also began with a simple wish to create a festival among the uninvited.

Chung: In some ways, it was a lighter and more popular response than Heatherwick’s.

Park: While Heatherwick addressed the general public and Chon spoke to an architectural audience, doesn’t that make Heatherwick’s work more ‘public’ in a way?

Chon: To be precise, I don’t think Heatherwick was addressing the public at all. His work was aimed at decision-makers—people like officials at the SMG.

Chung: He even instructed participating artists to design their walls so that decision-makers or developers would want to adopt them immediately as actual façades. At the same time, Heatherwick wanted the work to be engaging enough for a thirteen-year-old with no architectural background.

Chon: In principle, a biennale’s theme should not advance the agenda of a single individual, but rather articulate a shared issue to which a community can collectively relate. Yet with so many biennales and triennales now, I sometimes wonder if taking a different, unconventional approach might be justified. As for the director placing himself at the centre—well, Woody Allen appears in his own films while directing them. Seen charitably, one could say it is not entirely indefensible. But I remain unconvinced whether this represents a meaningful new direction for the biennale, or whether the direction is even good. I simply wish the format of this Thematic Exhibition had carried greater conviction. In 1980, at the Venice Biennale, Robert Venturi, Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, and Arata Isozaki participated in ‘Strada Novissima’, an exhibition of façades. There, all façades stood on equal footing. By contrast, Heatherwick’s exhibition feels more like a tool to promote himself. Interpreted generously, one might say he is simply adept at business and that this is how he became a globally renowned architect. But, because the Biennale has been effectively privatised, I worry about the diminishing space for architectural public discourse. At times, I wonder if that space is now shifting to Instagram.

Chung: Formally speaking, though, I found it convincing. The Humanise Wall operates at an urban scale, aimed at people passing by on buses or looking from nearby buildings. Then, as you move inward, façades at a human scale appear in response. Some criticise the heavy construction, but I heard it was originally planned as a fabric structure and later changed to steel because it might blow away or fail under lateral wind loads. The concern about generating a massive piece of waste is secondary. When viewed as an approach to scale, I did not feel the format itself was the issue. The real problem is the low density of content on the Humanise Wall, and the ease with which Heatherwick dismisses modern architects by saying ‘modern architecture is boring’. I also saw criticisms noting that he approached the Biennale half-heartedly, but SMG officials told me he was the most dedicated director they had worked with—adjusting his presentations each time depending on the audience.

Chon: Just as Le Corbusier engaged with many cities before realising his masterplan in Chandigarh, Seoul has become Heatherwick’s own ‘Chandigarh’. In such a situation, it is natural for local architects to criticise him, and for others, like me, to begin asking: What kind of architecture is possible for us under these conditions?

Chung: Exactly—and it’s not as if Le Corbusier approached Chandigarh carelessly.

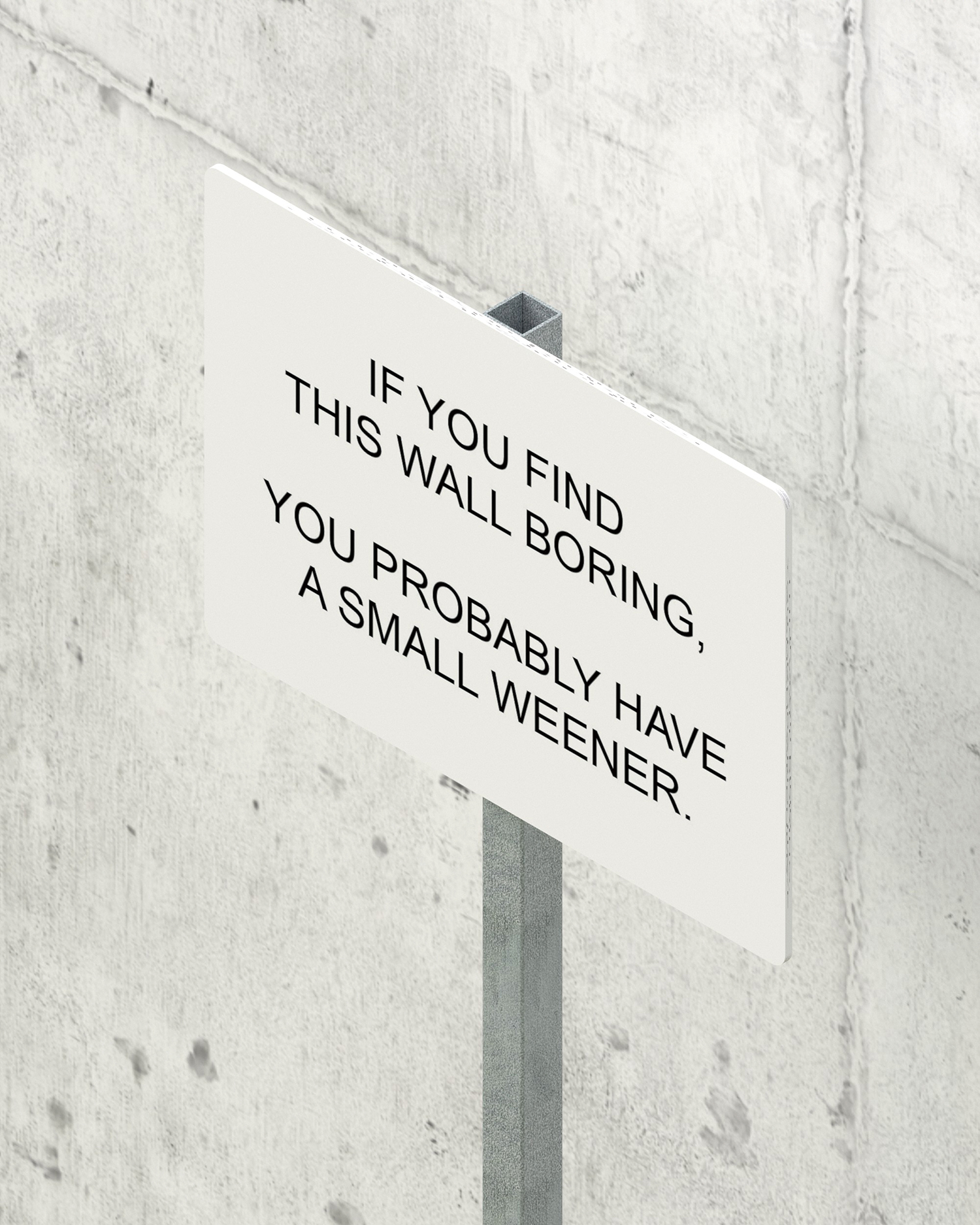

Punchline Wall (2025)

Not a Pavilion but a Mock-up: Residual Heritage

Chon: Looking at the evolution of Residual Heritage, I noticed that the wall began as a flat elevation and later became a façade with curves. Was that also something Heatherwick requested?

Chung: There was a request to make it more three-dimensional, and most participating artists received similar guidance about form. But the localisation of Western culture in Korea was already a key concept of our work, so borrowing the plastic, three-dimensional profile of the façade from the rock faces of Yosemite National Park was a natural extension.

Chon: Traditional floors finished with hanji oiled in soybean oil were replaced by PVC flooring as Korea industrialised. In this project you used oiled hanji again. What is your view on PVC flooring?

Chung: Many of our native traditions have been replaced by cheaper, more economical materials, and I simultaneously feel both affirmation and discomfort toward that reality. By tracing these substitutions, we can understand what we truly prefer, almost like reading our cultural DNA. I also sometimes wonder whether the results we see today were really the best possible choices. I imagine how things might have turned out if modernisation had moved more slowly, or evolved in a different direction. In that sense, rather than simply ‘improving’ PVC flooring, we chose to imagine hanji itself evolving into a robust, water-resistant material. Depending on the situation, we work flexibly: for another project, for instance, we used PVC flooring to build a raised platform with more refined detailing.

Chon: Earlier you mentioned that Heatherwick told everyone to think of the Walls of Public Life not as pavilions but as mock-ups. A pavilion is a standalone work, while a mock-up is essentially a promotional sample. As a participating architect, how did you take that piece of guidance?

Chung: Many architects can probably relate to this: even when your name is reasonably well known in the field, running an office can still be difficult, and that gap produces a certain dissonance. In that sense, I felt it was important to reflect on questions of commerciality and publicity.

Chon: When you looked at the other Walls of Public Life, which work do you think came closest to meeting this perspective?

Chung: I don’t think there was one work in which the intended concept could be grasped intuitively in a satisfying way. Once ‘intuition’ crosses a certain threshold, meaning disappears and only form remains, and I didn’t see many projects that handled that balance well. In terms of attitude, however, I thought YOAP architects (co-principals, Kim Doran, Ryoo Inkeun, Jeong Sangkyong) offered something exemplary. Perhaps their temperament simply aligned well with Heatherwick’s, but I was struck by how they set aside complaints and criticism and approached the work in a genuinely positive and sincere way.

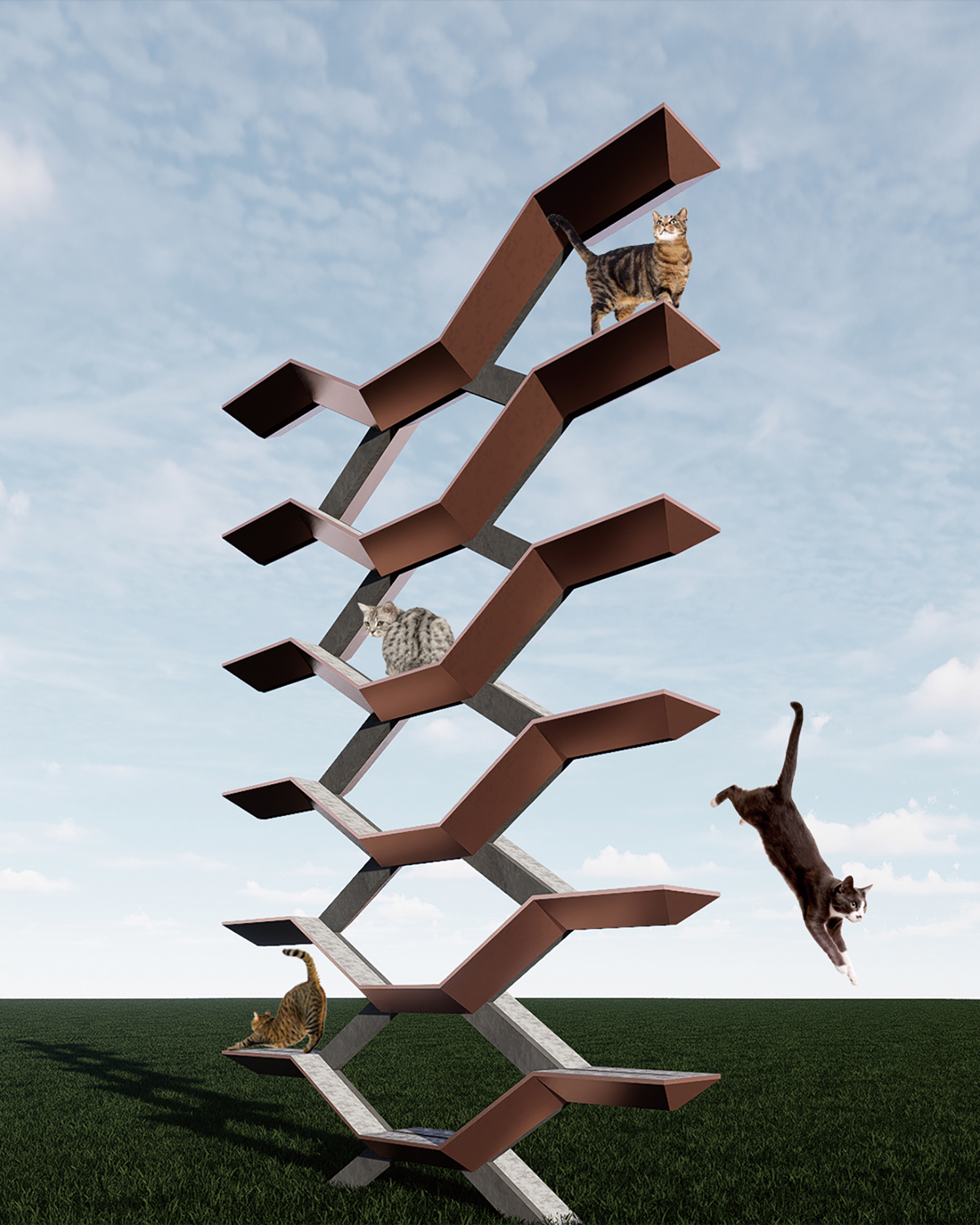

K-Wall Challenge entry; Cat To-Wall (2025) by Lee Deuku ©Lee Deuku

K-Wall Challenge entry; Resistance Wall (2025) by Saul Kim ©Saul Kim

Bunsik and Wine: The Punchline Wall

Chung: The format of the K-Wall Challenge – what you called a ‘Biennale outside the Biennale’ – reminded me of the episodes where artists not invited to major art biennales gain attention by turning to the streets. Looking at your past work, I felt your vocabulary spans a wide spectrum, from architecture to fine art, from subculture to high culture.

Chon: Since I was young, I spent a lot of time digging through the internet, including Wikipedia. (laugh)

Chung: The Punchline Wall feels like a project that strikes a balance across that spectrum. While Heatherwick criticises such walls as ‘boring’, it becomes an appealing surface for architecture enthusiasts, and by adopting the format of a ‘billboard’, you added content a graffiti artist might have painted.

Chon: Whenever I work, I always struggle with the question of whether my work sits closer to bunsik (street food) or to wine. Wine carries a degree of aspiration, so even if the field is difficult, people want to learn about it. Bunsik, by contrast, is stimulating and easily accessible. The two modes mix at times, but fundamentally, I pursue the ‘wine’ approach.

Chung: I also found your project using Lexan at the courtyard of the Korean Museum of Urbanism and Architecture (covered in SPACE No. 693) very interesting. I, too, am interested in using inexpensive materials like Lexan in better ways, but because it is a product name, I often hesitate to bring it forward as an architectural element. You, however, did not hesitate and used the most widely understood vocabulary in a direct way and I liked that. I’m curious, though: would you say that project was bunsik or wine?

Chon: Since Lexan is typically used for roofs and canopies, I would say giving it the form of a ‘forest canopy’ – a structural homage that turns it into a kind of tree – was a move rooted in architectural nerdiness. So, I consider it to be closer to wine. I’m more interested in people with niche tastes than those more generally shared. I believe that if people become engaged first, broader interest will eventually follow. Virgil Abloh once said in a lecture that we should target both tourists and pioneers. He argued that we should make work that speaks to both groups, and I try to follow that, though I’m not sure I succeed.

Chung: Yet, work that tries to please both ends often fails to win over either. I’ve made projects that sit between art and architecture, and at times they seem to fall into neither camp. When you try to satisfy tourists and pioneers, art and architecture alike, the work risks falling short—and it becomes even harder to translate into income.

Chon: Which is why I, too, think a lot about how interesting architectural discourse can function in the market. Viewed that way, Heatherwick has been remarkably effective—clear targeting, successful monetisation. And to be fair, many of his works are excellent.

Chung: I can accept the strangeness of his forms as a stylistic identity. The dissonance arises when he tries to justify them in architectural language.

Chon: Considering that, I wondered whether – even as a star creator with a massive portfolio – he also wants the title ‘architect’. And to be honest, because the architecture world is small – divided by generation, region, experience, and practice versus theory – I wanted to dissolve those boundaries and encourage everyone to play together. I thought it would be fun for each person to imagine their own wall under the same conditions, without hierarchies or judging criteria. But participation filtered itself naturally. I’m not sure why, but some people viewed the challenge through a political lens. I didn’t expect an Instagram challenge to be taken so seriously—yet for some, this field is tied to their livelihood, so perhaps my lighthearted approach felt uncomfortable. At the same time, the challenge opened opportunities for discussion about the Biennale, which I was glad to see. I’m still not sure how to interpret these reactions, but I’ve learned that there is a wider range of temperatures within the architecture community than I had assumed.

Chung: I’m also curious what you thought of the other works submitted to the challenge. The Punchline Wall humorously provoked Heatherwick’s ideas and curatorial intent without media prejudice, sitting between elitism and the public. But the subsequent works seem to have taken a slightly different direction.

Chon: Because Heatherwick had focused on form, I initially hoped the challenge would continue in that direction rather than becoming meta. I also liked Saul Kim’s work, which dealt purely with how the wall meets the ground. But because I started with a meta piece, many of the following submissions also took on a meta tone. The K-Wall Challenge is, in fact, an homage to the Ice Bucket Challenge—in that case, the fun lies in watching people get drenched; in this case, the burden is greater because people must show their own work. I nominated Hyunjoon Yoo (professor, Hongik University) to start the chain, thinking his wall would be one people were truly curious about – but he ultimately did not participate.

Park: Observing all of these responses, I wondered whether you are caught between generations. Older generations may feel distanced by your unfamiliar ways of thinking and expressing, while younger generations may already see you as part of the establishment and critique you. Yet you yourself, with no large-scale architectural work to your name, are thinking, ‘Who am I, really?’ Perhaps the question now is how you will continue to nurture your own sensibility in the face of such reactions.