SPACE January 2025 (No. 686)

Kim Kwangsoo principal, studio_K_works × Lee Jongkeun author

Transparent Society – Opacity

Kim Kwangsoo (Kim): Originally, Wonju Art Gallery (Sculpture Gallery) (2022) was conceived as a sculpture gallery, with commissioned works tailored to the space and its surroundings. However, after the gallery was completed, the mayor changed, and the commissioning process was halted. The building was eventually named ‘art gallery’ by the client. The site is located within a large neighbourhood park in Dangu-dong, Wonju-si, surrounded by extensive apartment complexes. When I began designing, I often observed residents walking up and down the park’s hills, circling the area during mornings and evenings. This was in May 2020, during the unfolding of the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic. While people were confined indoors, paradoxically, society was accelerating toward hyper-connectivity and becoming increasingly transparent and surveillant. When pandemic restrictions were lifted, even internationally, tools like Google Maps ensured seamless navigation. Opportunities for unanticipated discoveries or experiences became scarce, and the true ‘outside’ seemed inaccessible. It felt as though the unfamiliarity of the external world had been erased. In this environment, I sought to explore the internal more deeply, seeking externality within. This work became a dialogue with Aldo van Eyck’s Sculpture Pavilion (1966).

Lee Jongkeun (Lee): If the Wonju Art Gallery emerged from a societal context that erases unfamiliarity, what physical context recalled the Sculpture Pavilion?

Kim: Its modest size, about 100-pyeong (330m2), and its role as a sculpture gallery brought Aldo van Eyck’s project to mind. He was a modernist architect I greatly admired for his unique approach to transparency, distinct from that of his contemporaries.

Lee: Aldo van Eyck’s designs were distinct from typical modernist architecture. As architecture students, however, we carry memories of numerous architects, not just Aldo van Eyck. Was it primarily the gallery’s scale and purpose that evoked his project?

Kim: Yes. I also enjoy engaging in imagined conversations with architects of the past.

Lee: Aldo van Eyck’s Sculpture Pavilion came from a 1960s context, different from our social and physical context. How did you address these contextual differences?

Kim: The Sculpture Pavilion uses freestanding walls layered over flat terrain. In contrast, the Wonju Art Gallery is situated at the base of a mountain, and mountains hold particular cultural significance in Korea. I also considered the daily movements of local residents navigating the hills. My design sought harmony with the topography and connection between the dynamics of the park with the pathways of the community.

Lee: What elements of Aldo van Eyck’s architecture did you reinterpret? Was it the forms, the spatial dimensions, or both?

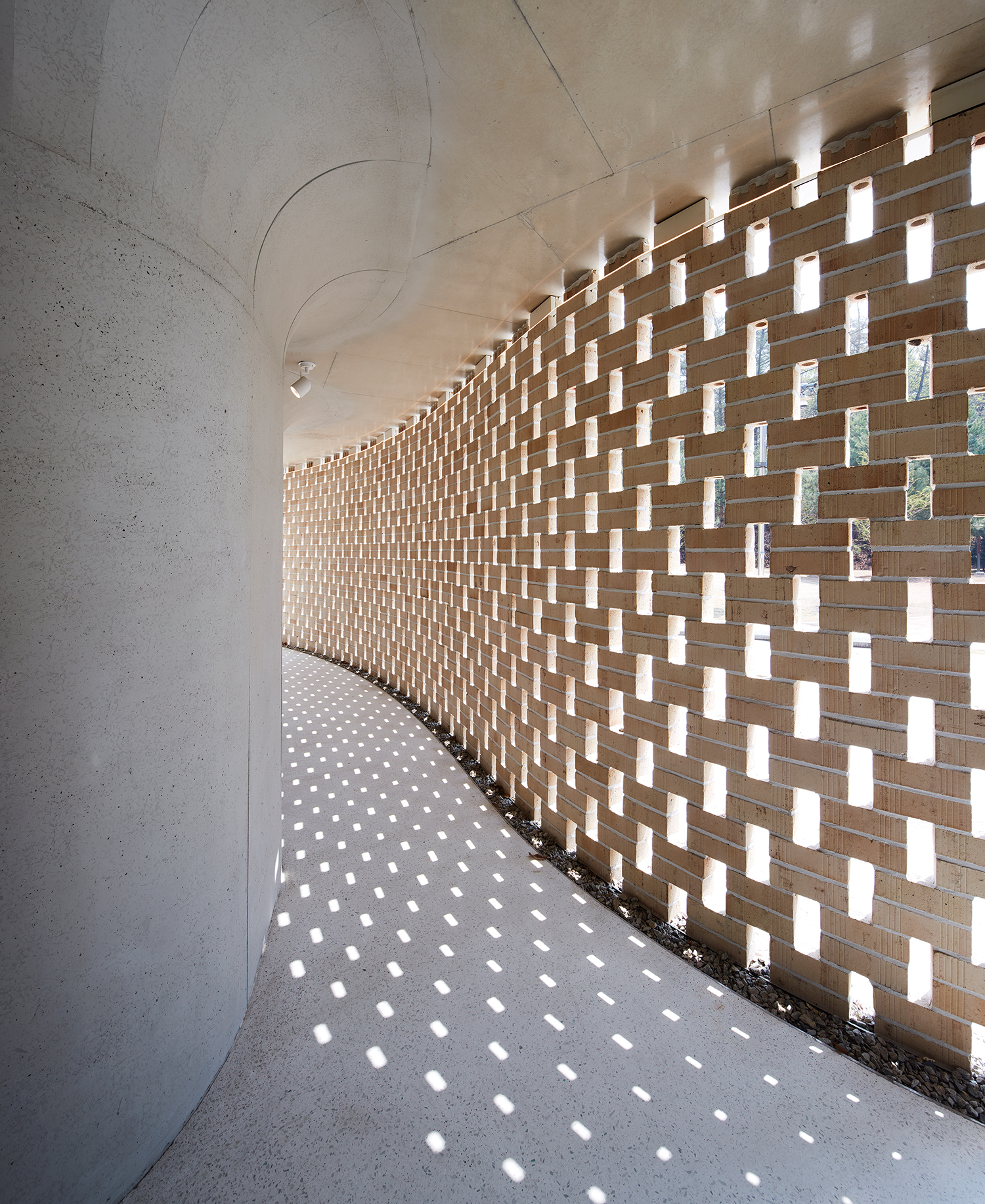

Kim: I focused on the sense of opacity and the maze-like quality of alcoves. While Aldo van Eyck layered walls, I used a single continuous wall or line that seamlessly integrated with the roof, creating paths that bifurcate and lead to alcoves. These spaces hold a sense of opacity and depth, where sculptures can be encountered unexpectedly. Unlike Aldo van Eyck’s maze, where exits are visible, I emphasised disorientation and kinetic shape (動勢), aligning flows with the mountain’s topography.

Lee: One of the commonalities between Aldo van Eyck’s project and yours is the intimacy of the spaces. These are not collective viewing spaces but ones that invite solitary engagement. The experience is not about observing an entire space from a distance but about forming a sensuous and intimate connection, tied to proximity and scale. Rather than focusing on transparency and opacity, I would associate your project with discontinuity and continuity. The space isn’t experienced as a continuous path but rather as a sequence of interruptions and divergences, creating heterogeneous replication. Colin Rowe once described spaces with ambiguous directionalities as ambiguous because one could either proceed or pause. The Wonju Art Gallery carries a similar ambiguity: it feels like a pathway but equally invites one to stop. Reflecting on this, perhaps influenced by the pandemic, I thought, ‘Ultimately, we are solitary beings.’

Social Space – Object-Oriented Architecture

Lee: In galleries and museums, the essential experience comes from engaging with artworks not abstractly but concretely and physically. Beyond that, it is about immediately sharing one’s experience with others. This is why rest spaces are so important. In Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum (1972), the central bay serves as a space where visitors can exchange impressions of the artwork before the tactile experience fades. What role did social space play in this project?

Kim: The main hall of the Wonju Art Gallery was originally intended to serve as a café. The idea was for residents to casually visit, share conversations, and rest after viewing the artwork.

Lee: I believe that space is the essence of a museum. Social spaces allow visitors to catch glimpses of artworks, return after viewing, and share their personal experiences. This enables individuals to identify and navigate differences between themselves and others, transforming isolated experiences into social connections. Such spaces provide a foundation where art and life can intersect. Without them, unique experiences might evaporate, as if one had watched a solitary film in a private screening room. However, it seems the café isn’t currently being used as originally planned.

Kim: That is correct. I understand that local merchants opposed having a café in the gallery, and after the previous mayor’s term ended, the café facilities were removed. It was converted into an exhibition space, but its current use feels somewhat ambiguous. This change is disappointing because the original plan was to commission sculptures for the alcoves and extend the park into a full-scale sculpture park. I also consider social spaces essential, but I feel there are issues worth addressing. Many modern museums tend to let architectural or exhibition design overpower the content, leading to a disconnect between artworks and their spaces. Architecture frequently seeks to establish itself as an artwork before allowing the content to be engaged. This trend has raised critical concerns for me, and I sought instead to foster an integrated and unique relationship between architecture and the artworks. Additionally, modern museums have proliferated social spaces to the extent that they are sometimes indistinguishable from shopping malls.

Lee: Excessively so. Since the 1990s, discussions around museum sustainability have often focused on incorporating commercial spaces. As a result, nearly all major galleries now feature elegant restaurants and cafés. This transformation has turned museums into spaces for dining, coffee, and dating—a complete inversion of their original purpose.

Kim: Hito Steyerl referenced Harun Farocki’s artworks to highlight how factory workers from Lumière’s era now return to museums – modern factories – on weekends. This criticism points to the commercialisation of art and the transformation of museums into commercial spaces.

Lee: Ironically, such critiques emerged precisely at a time when architects, artists, and many humanities scholars began calling museums ‘the cathedrals of the 21st century’. Museums were regarded as the last sacred spaces amidst the secularization of other spaces. Paradoxically, they began to secularise just as they were recognised as cultural pinnacles.

Kim: That shift also marked the rise of end-of-art narratives.

Lee: Perhaps this is why the idea that ‘architecture itself should be an artwork’ gained traction. Architecture moved from being the background for museums to becoming a centrepiece in its own right.

Kim: The Guggenheim Bilbao Museum (1997) played a catalytic role, prompting cities worldwide to pursue architecture-as-art. However, these efforts often demanded immense capital and created situations where artists seemed displaced by the buildings themselves. This dynamic risks undermining the autonomy of artists. That said, I find myself conflicted. Creating specific alcoves within a 100-pyeong space and requiring artists to adapt their work to these spaces may seem one-directional or even coercive. On the other hand, haven’t neutral, indefinite exhibition spaces dominated long enough? This may explain why artworks in such spaces can feel transparent. In modern museums, there often seems to be no reciprocal interaction—where the artwork invades or draws the viewer into its space. Without significant effort or attention, visitors tend to skim through exhibitions, take a few photos, and leave quickly. There’s also the notion that sculptures must always be appreciated in 360 degrees, which I question. Rather than neutrality, I aim to design spaces where the architecture and artworks work together to create unique experiences.

Lee: As Manfredo Tafuri noted, there was a period when object-oriented architecture faced significant criticism. Among architects, it was often dismissed as decadent or anachronistic. The prevailing belief was that architecture must remain abstract, which became a kind of dogma.

Kim: Especially in Korea, there has been an increasing aversion to anything conspicuous. However, this often leads to a default toward modernist styles, which I also find difficult to embrace.

Artificial vs. Natural / Kinetic Shapes

Lee: The Wonju Art Gallery doesn’t seem to stand out; rather, it conforms with the surrounding terrain and maintains a calm demeanor. It appears to be a response to various programmes and intentions.

Kim: Responses manifest in many ways as shapes. I also questioned whether this work stood out or not. I neither intended for it to blend in nor to stand out, yet I’ve heard people describe it as conspicuous.

Lee: This has been a long-standing feature of the discourse in East Asia, particularly in Korea, where the notion that ‘buildings must conform with nature’ has dominated architectural thought. How have you reflected on the relationship between the artificial and the natural, especially in terms of conformity or dominance?

Kim: I’ve long questioned the binary framework of dividing the artificial and the natural. To me, the artificial is a part of natural phenomena, and nature, when viewed through the lens of instrumental rationality, becomes artificialised.

Lee: In terms of architectural geometry, distinctions are often drawn by phrases like ‘there are no straight lines in nature.’ Philosophically, figures like Martin Heidegger have argued that humans emerge as human by separating themselves from nature. Through this separation, civilisation and culture are formed. Humanity thus exists in a dual predicament: objectifying nature while simultaneously being a part of it.

Kim: My critique targets the widespread tendency to conceptualise artificial and natural as inherently separate. These days, the focus seems to be on incorporating nature into artificial constructs. For example, 5.16 Plaza was transformed into Yeouido Park, and the Nanjido landfill became an ecological park. I believe that embracing a dual perspective – balancing ideals with reality – is crucial because the artificial / natural dichotomy tends to obscure the reality of such spaces.

Lee: There are forms of artificial nature and absolute nature—nature beyond human intervention. Since we are born and live in urban environments, cities effectively become a second nature. While it may be difficult to draw a strict line between artificial and natural, for the sake of discussion, I would argue that the Wonju Art Gallery conforms to nature. It integrates with the terrain like an eyebrow following the ridges and contours.

Kim: Observing the mountains, contours, and the movement of residents along walking paths, I hoped to infuse the work with ‘kinetic shapes’. Whether this qualifies as conformity, I’m uncertain.

Lee: Conformity avoids disruption or opposition. However, in this case, there is a reversal between the external shape and the internal space. Without such reversals, the design might have lacked clarity.

Kim: I intentionally incorporated subtle discomforts. For instance, the entrance doesn’t explicitly declare itself as the main gate. Instead, visitors can enter from multiple points, and once inside, they encounter a circulation designed to be disorienting.

Lee: I also believe that the architectural value of the Wonju Art Gallery lies in its ambiguity. It disrupts flows, confuses entry points, and blurs boundaries between the interior and exterior. Even the variations in height and the interplay of natural and artificial light are ambiguous.

Kim: I considered the sensations of compression and expansion. Although the space measures only 100-pyeong, the plan might feel closer to 500-pyeong. This compression was intentional, as I wanted to emphasise spatial intimacy. At the same time, I hoped the experience would expand outward into the mountain ridges.

studio_K_works + Curtainhall (Kim Kwangsoo)

Kwon Hyuktae

1708 and 1 parcel, Dangu-dong, Wonju-si, Gangwon-

culture and assembly facility, neighbourhood livi

54,246㎡

326.17㎡

324.89㎡

1F

5

3.8m

0.6%

0.6%

RC

exposed concrete, brick

exposed concrete, paint

Millenium Structure Engineering Co., Ltd.

Jusung Mechanical Engineering & Consulting

Woorim Electricity

Muhan Construction Co., Ltd.

May – Nov. 2020

May 2021 – Oct. 2022

1.52 billion KRW

Wonju-si Office