SPACE December 2024 (No. 685)

interview Špela Videčnik co-principal, OFIS arhitekti × Kim Bokyoung

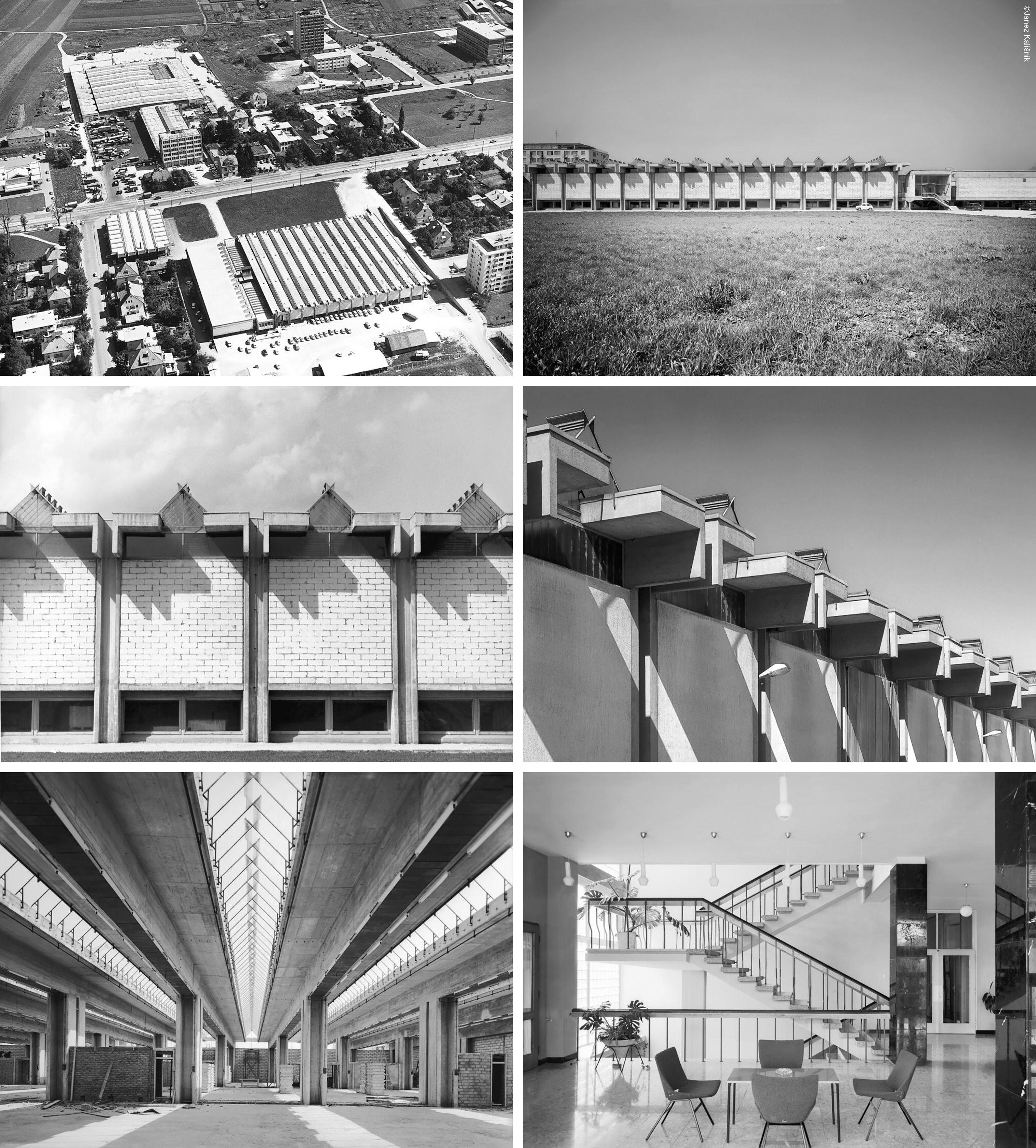

Kim Bokyoung (Kim): This project is the renovation of the Mladinska Knjiga Printing House which was designed by the Slovenian modernist architect Savin Sever (1927 – 2003) in the 1960s.

Špela Videčnik (Videčnik): The modernist roots of architecture in Slovenia are very profound. Savin Sever was a student of Edvard Ravnikar (1907 – 1993). Ravnikar was a key figure during this period in Slovenian architecture. He studied and collaborated with Le Corbusier and was also deeply influenced by him during his time at Le Corbusier’s studio. Ravnikar developed his own architectural poetics, both drawing on tradition and advancing its themes with a modernist approach that became the mark of Slovenia’s post-war generation of architects. Sever is one of the most prominent representatives of this so-called Ljubljana School of architecture. Luckily for them, the socialist government at that time supported their architectural style. Therefore, Ravnikar and his students could command key tasks in the post-war reconstruction of socialist Slovenia and Yugoslavia. Sever designed several factories and industrial buildings, but unfortunately some of them were demolished.

©Janez Martincic

Kim: What do you think is the most valuable thing to be preserved in this building?

Videčnik: The Mladinska Knjiga Printing House (1966) was modular and prefab. The modular, repetitive concrete construction was Sever’s distinctive architectural expression and a characteristic feature of the post-war modernist period. The massive concrete beams which held large scale spans allowed for large spaces to place printing machinery. Because of this modular system and a spatial structure that permitted flexible rearrangement and repurposing of space into various modern uses without requiring extra support, the Mladinska Knjiga Printing House became recognised as an architectural monument. Personally, I would also like to mention the triangular-shape glass prisms (skylights) that allowed natural light into the factory. The façade looked very simple from the outside, but the most important elements were located above. Glass prisms placed between the concrete elements allowed natural light to penetrate deep into the building. They also had a special mechanism so you could open them and draw fresh air inside if needed.

Kim: Perhaps because this was a work by a historically prominent architect, this renovation project was more of a restoration than an extension.

Videčnik: Yes. Because it is iconic in the architecture of Sever, we wanted to keep our work minimalistic. The existing building was not insulated at all—its façade was simply made with bricks. The building needed to be insulated to be used for other purposes aside from a printing house. It is generally hard to insulate exposed concrete structures since all the concrete beams act as thermal bridges. Also, more importantly, we had to resolve this thermal insulation problem while keeping the original looks and spatial impressions. And, so, our initial approach was to simply create a heated space inside and hide it from the outside. While working, however, we discovered Sever’s old drawings of the Mladinska Knjiga Printing House and learned that he originally planned to use concrete panels as cladding for the façade but that this was not realised. This finding made us very happy because this meant that we could thermally isolate the building by adding concrete panels. It was the best of both worlds: restoring the original design and solving the thermal insulation problem. We added interior and exterior thermal isolation where they were needed and deliberated on which structural elements should be exposed. For example, while the concrete beams are exposed to the inside, they are also hidden under the roof that is thermally isolated from the outside. The original window frames, including that of the triangular skylights, were metallic and were also not thermally isolated. We carefully redesigned every window for thermal isolation.

©Janez Martincic

Kim: You had to convert the building which was originally designed as a printing house into a commercial building and office.

Videčnik: The biggest change was the addition of a new southern entrance. Originally, the printing house’s workers entered the building through the staff room of the office block, but this circulation route was not appropriate to the building’s newly added programmes (i.e., IT office and gym), so we added a new entrance on the southern side. Despite these newly added programmes, we wanted to retain the core characteristics of the original printing house. I mean the large space created with massive concrete beams with wide spans. To keep these characteristics intact, we created a space at the new southern entrance that resembles that of a city plaza. Spontaneous dialogues, presentations, and events can take place there. Moreover, parts of the old printing machinery were placed in the lobby to preserve and remind visitors of the building’s past. We designed the small office rooms to make them appear like small boxes in a large space. The office rooms are separated into two floors, but they appear to be on the same floor when seen from the interior.

Before renovation

Before renovation

Kim: It is surprising that the preservation project of a building on such a large scale was initiated not by a public body but by a private client. How was this possible?

Videčnik: We think that it is very difficult to preserve architectural heritage in Slovenia. For example, buildings built in the 1960s and 1970s have long been neglected by both the public and the government. For a long time, Slovenia used to be a part of the socialist country Yugoslavia. When the socialist regime ended in the late 1990s, people were generally scornful of modernist architecture because they reminded them of the socialist past. Architects and artists showed interest in modernist architecture, but these buildings were not well-preserved. However, things have turned for the better recently. Various media are covering why such buildings are important, and yet the preservation of architectural heritage sites will remain insurmountably difficult unless there are clients who understand and recognise the cultural value and the significance of such an endeavour. Even Sever’s Bažato Gallery – which was meticulously renovated by the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia – is not public property. And there are almost no private clients who are willing to bear the burden; they would rather dismantle these old buildings and replace them with high-rise buildings. We think that the government’s role in preserving heritage is key. If the government designates a building to be a historical monument, not even the owner can dismantle the building at will. The printing house’s past owners left the building unmaintained and unrenovated while running low-budget programmes. It was once used as a skating rink, warehouse, and a part of it was used as an exhibition space. The building was treated as nothing more than a temporary space. The new client knew that this building was designated as an architectural heritage before purchasing the building and its surrounding land. While the client acquired permission from the government to build a residential district in the surrounding area, this building could not be dismantled. As such, the client chose to preserve and renovate it as a contemporary office and fitness space for an IT company. This was the reason why this printing house got preserved.

©Janez Martincic

Kim: Will you continue to work in heritage preservation projects?

Videčnik: Yes. More than 50% of the work at OFIS arhitekti is related to building preservation, reuse, and renovation. We preserve, renovate, and repurpose many buildings while expressing our distinct architectural language through them. In Slovenia, various forms of architectural styles ranging from Roman architecture, medieval architecture, baroque architecture, and modernism architecture can be found. From such buildings of diverse periods, one can discover multiple characteristics that can be integrated into the contemporary lifestyle. We apply this approach not only to historically important architectural heritage sites but also to other aged buildings. We think that as long as the structure remains stable, the building should be maintained. There is a lot of discussion in the architectural world concerning carbon footprints when building or dismantling buildings. There is no reason to dismantle a building just because it is old.

OFIS arhitekti (Rok Oman, Špela Videčni

Janez Martinčič, Andrej Gregorič, M

Dunajska cesta 123, Ljubljana, Slovenia

mixed use

9,050㎡

12,800㎡

10,800㎡

2F

166 (car), 129 (bike)

RC, steel frame

concrete, fibre cement façade board

concrete, silicone-reinforced finishing

Project PA d.o.o.

ISP d.o.o.

Pro-elekt d.o.o.

Tolstojeva d.o.o.

2021 – 2022

2022 – 2024