SPACE March 2024 (No. 676)

Interview Joshua Ramus principal, REX × Park Jiyoun

Park Jiyoun (Park): As a key piece in Daniel Libeskind’s master plan for the post-9/11 World Trade Center site, could you explain the role of the Perelman Performing Arts Center at the World Trade Center (PAC NYC) within the mater plan?

Joshua Ramus (Ramus): In the Libeskind’s master plan, there are office centres and public buildings (an iconic new transportation station and a performing arts centre). Embracing the restorative power of art, PAC NYC is the cultural keystone and final public element in the master plan. A producing house for music, theatre, dance, opera, and film, PAC NYC has a pure form – rotated and elevated to accommodate complex below- and at-grade constraints – and is wrapped in translucent marble.

Park: Unlike the surrounding buildings, which were designed using transparent glass curtain walls, your building is finished with translucent marble curtain walls.

Ramus: The entire 117ft (35.7m) marble-glass skin is a single, supple drape suspended from the top of the building that satisfies stringent thermal expansion / contraction and anti-terrorism requirements. Regarding the contrast with its clear glass-clad neighbours, it was a condition stipulated in the master plan design guidelines that commercial activities – such as ticket sales, restaurants, bars, etc. – were not to be visible from the 9/11 Memorial (hereinafter Memorial). The façade is informed by this line of reasoning. By day, the volume is an elegant, book-matched stone edifice acknowledging the solemnity of the Memorial across the street. By night, this monolith dematerialises, subtly revealing the creative energy inside.

Park: How would you describe your creative discussions with façade consultant Front (principal, Bruce Nichol) to realise this marble façade?

Ramus: Our discussions focused on cost-efficiency and technical viability. From an economic standpoint, the façade is the result of an intense optimisation exercise, balancing the cost drivers for marble slabs with those of a complex curtain wall. The 5 × 3ft (1.5 × 0.9m) dimensions of the insulated marble-glass panels were highly efficient in terms of quarrying the marble blocks, slabbing the blocks, cutting the slabs into tiles, honing the tiles, laminating them between glass lites, integrating the laminates into insulated glass units (IGUs), and fabricating the IGUs into cassettes. This size, however, is not cost-effective for shipping and installation. But by grouping the 5 × 3ft cassettes four tall into mega-panels, we created 5 × 12ft (1.5 × 3.7m) units that adhere to the standard dimensions of office curtain wall panels pervasive in the façade industry.

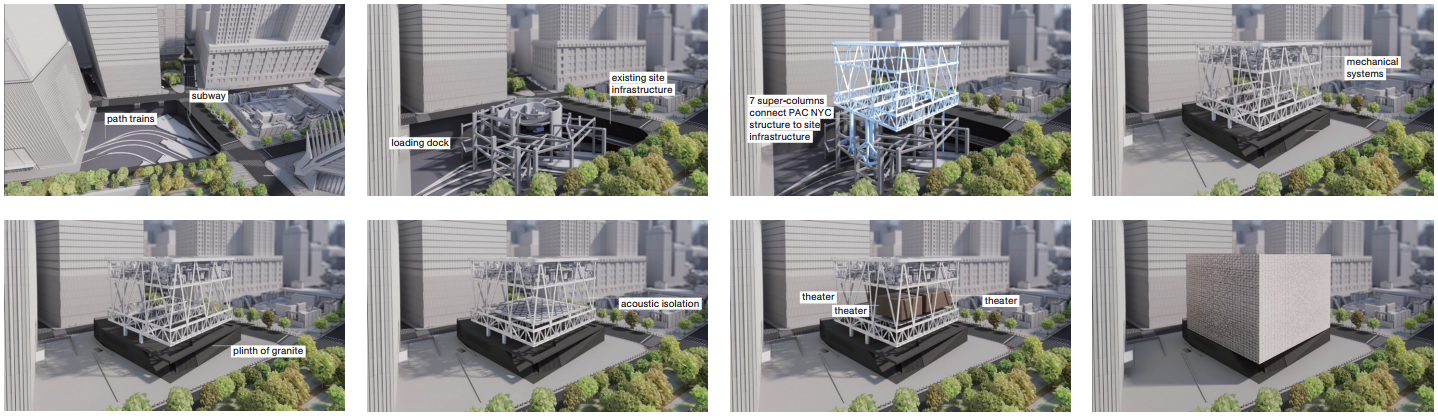

Process diagram

Park: Part of the foundations were already laid as the remnants of Frank Gehry’s design which began in 2004 but were suspended in 2013. Specifically, what stage of development was the project at when you picked it up in 2015?

Ramus: None of the above-grade stylobate was built when we commenced design in 2014 after Gehry’s project was suspended in 2013. PAC NYC’s structure, however, does respond to the foundations of Gehry’s design, which provided minimal bearing capacity for our new design’s reduced footprint. The structure is intertwined with four subterranean levels of infrastructure, including train tracks, subway lines, and high-security truck circulation, all while accommodating stringent blast and acoustic isolation requirements. To overcome these constraints, seven ‘super- columns’ thread through the below-grade infrastructure and branch out like spider webs to grab bearing capacity wherever possible. From these awkwardly spaced super columns, the structure was reverse-engineered, resolving the columns into a structural plate, on top of which a massive belt truss ties the entire building together.

Park: There were also restrictions regarding the loading dock.

Ramus: The master plan dictated that none of the loading docks for the World Trade Center’s buildings could be at grade. They are all two stories underground, connected by the high-security truck roadway that runs – also two stories down – around the Memorial’s perimeter. There are two points of access to this subterraneous truck circuit, one at the south side of the site, and one under PAC NYC. For this reason, PAC NYC’s lobby is elevated 21ft (6.4m) in the air: it sits atop the truck entry and its massive, two-storey spiral ramp that leads to the loading docks below.

Park: As a place for staging performances, the prevention of unwanted vibrations and noise from passing trains must have been a design priority. Could you explain your design approach regarding this challenge?

Ramus: On top of the plate and within the belt truss are nestled three highly reconfigurable theatre spaces. Like ships in a bottle, the auditoria is box-in-a-box structures, floating independently of each other and from the rest of the building on 1ft-thick (0.3m-thick) high-density rubber pads, allowing simultaneous performances while protecting them from low- frequency vibration caused by the trains, subways, and trucks below. In terms of the inside noise, our approach was achieved using four massive acoustic ‘guillotine’ walls that extend to the ceiling in a matter of seconds using scoreboard lifts.

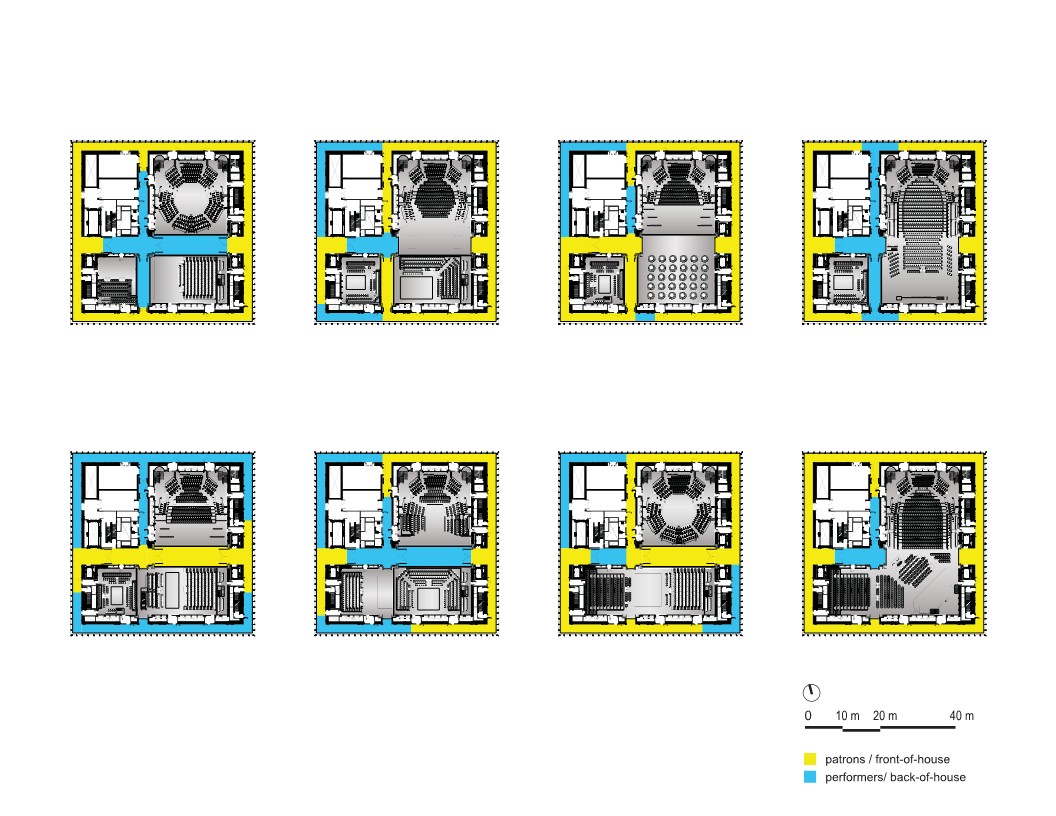

Park: By using movable walls and spiral lifts, you designed a space that can be reconfigured spatial compositions. You can adjust the height and inclination of the floor as well as the seating arrangement. What kind of art space did New York City request?

Ramus: Most people do not realise the extent to which the characteristics of a performing arts building dictate the art that is presented within its walls. From the moment in 2013 when PAC NYC was reconceived as a not-for-profit organisation that would produce and co-produce original work, it demanded a different kind of performing arts ‘instrument’, one capable of responding to the myriad nascent visions of its artistic directors and artists. For this reason, PAC NYC is a ‘theater machine’ that can assume 10 different proportions and more than 60 stage-audience configurations, ranging from 90 to 950 seats.

Park: REX was originally called OMA New York until it was renamed in 2006. How has your relationship with OMA developed over the past two decades?

Ramus: I have similarly retained my belief – honed on projects I worked on at OMA, such as the Seattle Central Library (2004) – that architecture should actively empower its users and communities, not simply be a representational art. At REX, we therefore emphasise the power of performance, a hybrid of form and function calibrated to each client’s aspirations and each project’s constraints. Unprejudiced by conventions, preconceived aesthetic strategies, or outcomes, we return to root problems and doggedly explore them with what we call ‘critical naiveté’. Through this process, we expose solutions that transcend those we could have initially or individually imagined, and aspire to produce inventive designs so functionally specific that they offer new and inspiring aesthetic experiences. Fundamental to this process is the creation and constant editing of a narrative embodied in text and diagrams. I believe that until we can clearly articulate such a project narrative, we are not in full control of the project’s design problems, and hence must continue developing the architecture response.

Park: During your interview (covered in SPACE No. 506) in 2010, you once mentioned that ‘the utter lack of urban ideas regarding New York City’.

Ramus: My concerns remain. Since 2010, the major addition to New York’s ‘progress’ is the 25 billion USD Hudson Yards, about which Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic for The New York Times, wrote: ‘It is, at heart, a supersized suburban-style office park, with a shopping mall and a quasi-gated condo community targeted at the 0.1 percent. A relic of dated 2000s thinking, nearly devoid of urban design, it declines to blend into the city grid.’ Clearly, I am not alone in my doubts about whether New York is cementing its status as the most forward-looking city in the world. However, while grand urban ideas are lacking, some glimmers of possibility also appeared, which were less about progressive urban ideas and instead simply good, sound investments in improving the city.

REX (Joshua Ramus)

Alysen Hiller Fiore, Maur Dessauvage, Adam Chizma

251 Fulton Street, New York, U.S.

culture and assembly facility

3,600㎡

12,000㎡

42m

0.3%

3.3%

steel frame

marble, glass

walnut plank

MKA (Jay Taylor), Silman (Nat Oppenheimer)

Sciame Construction (Frank Sciame)

2014 - 2020

2018 - 2023

500 million USD

Front

Jaros Baum & Bolles