SPACE February 2024 (No. 675)

The architect, after looking around a neighbourhood park, selected a slightly raised area, which was rather untidy as it was used for chopping wood. He thought it was a good idea to clean up this messy place and build something new. He suggested creating a wooden structure at a place where trees were being removed. This was his first time building with wood. The building, starting from the southeast, spiraled upwards in a clockwise direction, making a roof that looked like it was recreating a lost peak. When I walked around the library and heard the explanation, the complicated design seemed understandable. It was easy to picture the whole building with its spirals, organised bookshelves, layers of roofs with light coming through, ramps and corridors connected to walkways. As I left the building, plaques showing the architecture awards hung on one side, demonstrating that a true expert does not simply rely on materials and tools.

‘Although I relied on a specialist company for the wooden structure this time, next time I want to try working with the wood structure more freely myself!’ says Jang Yoongyoo (co-principal, Unsangdong Architects). (Just so you know, Jang Yoongyoo is a senior colleague from my school and student’s studio).

The Library’s Landscape

On a brisk cold weekend day, I visited the library again. Around the low-rising Wolgoksan Mountain, apartment complexes and school facilities stood in contrast to the park and residential areas. At the front of the building, I was still concerned about the height of the entrance corridor. The lowest part of the eaves, about 2m high, seemed a bit cramped. I remembered hearing two days ago that they had lowered the overall height to fit the construction budget. It was disappointed.

I entered through the door. There were many people. Despite the cold, the inside was bustling like a popular neighbourhood café. Out of the total 431m2 (about 130-pyeong), excluding the corridor, about 40 people were sitting in groups in the 260m2 (about 80-pyeong) indoor space. The shape was like a conch shell, but the sense of space felt layered like an onion. The most popular spot was on the east side, an open area without bookshelves, overlooking the valley. People seemed to wait for a spot to open up there and then moved to it. Although it felt narrow, the space was not too uncomfortable to use. There were simple items like foldable chairs to sit and read, baskets to store coats, and other small but helpful things. A small café in the corner also contributed to the atmosphere. People were reading books, occasionally sipping coffee, and spending a fulfilling weekend under the sunlight coming through the roof.

Spirals in Space, Spiral-Struck Structure, and the Precision of the Bookshelf Wall

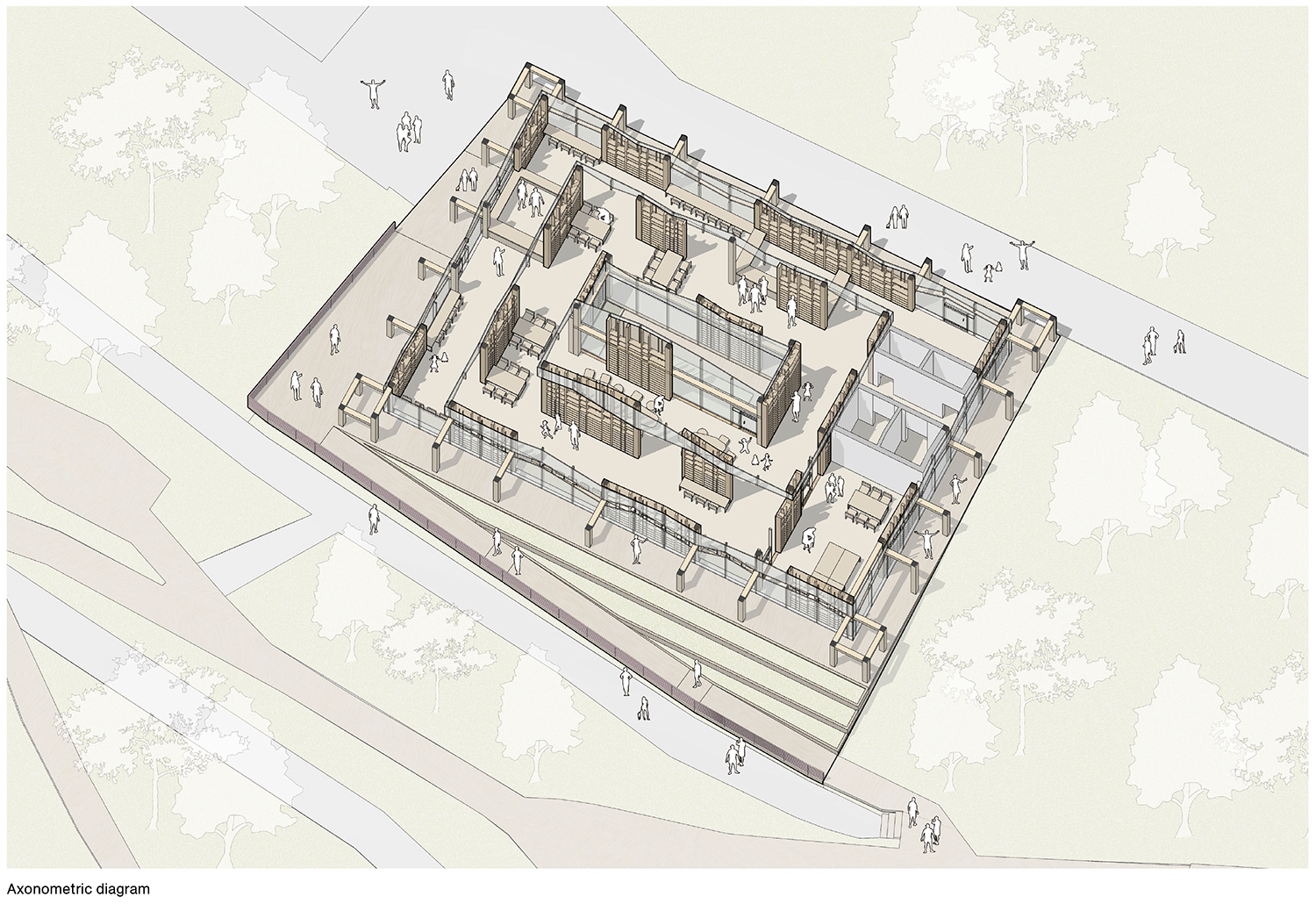

At Odong Public Library (hereinafter Odong Library), the floor plan shows that the dimensions are all different, not standardised like modules. If the spiral-connected spaces are considered pathways, then, roughly speaking, the community space in the centre is 4m wide, frequently used paths or staying areas are 3m or 3.3m wide, and narrower paths are about 2.5m wide. The corridor narrows down, but on the east side, it widens to a comfortable 3m, like a terrace.

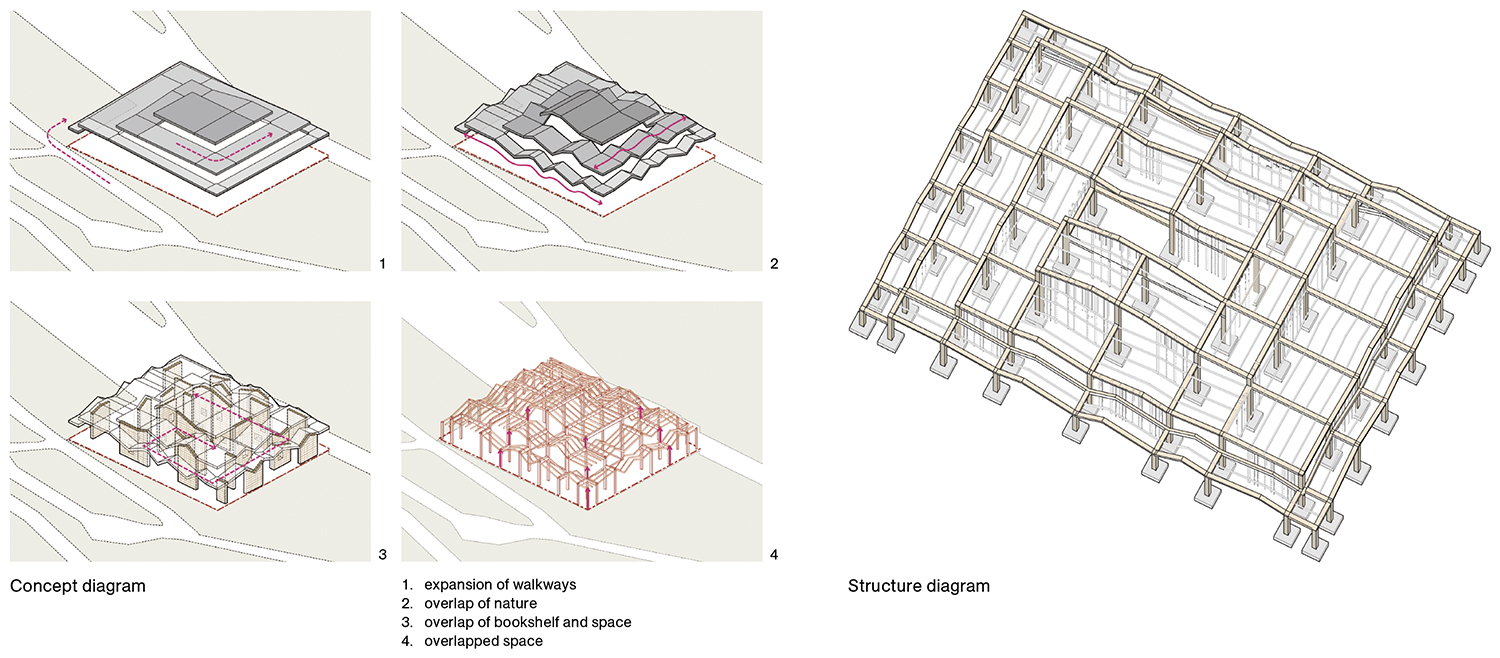

What’s more interesting is that pillars stand at every intersection of the central line. This makes sense when considering the construction process. Starting with the community space in the middle, tall pillars are erected, and then the surrounding layers lean on these tall pillars, fitting beams and adding new pillars at the other ends. As layers are added outward, with pillars and beams, and a roof on top, a corridor layer on the outermost part completes the large framework of the wooden structure.

The ‘folded roof’ that goes up and down in spirals is like a Chinese dragon dance, where sticks support the dragon, with each pillar and beam supporting the roof. The roof shape and structure are closely intertwined. The designer placed and adjusted the ‘bookshelf wall’ with precise height and width between the pillars as structured furniture. This allows for an unobstructed view, with the sky visible between overlapping roofs above and horizontal layers of space and landscapes beyond below, creating a dynamic and transparent sense of space for visitors. It’s an ingenious solution that incorporates the windows into the roof structure.

Reflecting on Odong from Hannae

After the impact and lingering feelings of a movie or a building subside, a kind of quiet reflection emerges. Then you start to wonder why you felt that way and examine it closely. That’s what reflection is. Despite the Odong Library being popular among citizens and winning several architecture awards, my personal impression of it was ‘confusing and claustrophobic’. I looked at the design documents and studied the design process but couldn’t find the fundamental reason for this feeling. Then I remembered something the architect said: ‘In Hannae, the structure and bookshelves were separate, but I wanted to integrate them...’ With the mindset of an architectural detective, I decided to go and see this work for clues.

Hannae Forest of Wisdom (hereinafter Hannae Library) was impressive. Even five years after completion, it had elegance and aura. Under the large gabled roofs with bookshelves on both sides, people were sitting at long tables reading, and, beyond them, a quiet snow-covered park was visible. There was a book café in the corner with a door leading to the park. I could see a courtyard where light filtered through layers of differently sized gabled roofs. After seeing Hannae Library, I understood the changes in the Odong Library design process. Odong Library followed Hannae Library’s example by having a book café in the corner and a large central courtyard. The continuous gabled roofs in Odong Library, referred to as ‘folded roofs’, were also similar to Hannae Library’s architectural language.

The biggest change in Odong Library was in the conceptual form of space-structure integration. While Hannae Library was based on a single axis towards the park, like a ‘wave moving horizontally’, Odong Library changed to two axes, or perhaps three including height, towards the neighbourhood park, resembling a ‘mountain spirally rising’. As a result, Odong Library developed a free nomadic quality instead of Hannae Library’s stable sense of space. In Odong Library, the café didn’t have a separate drinking area, allowing people to drink coffee they got from the counter anywhere they chose. The light coming through the spiral roofs replaced the need for a central courtyard to bring light into the middle of the building. The problem arose as the layers of space, including the corridors, increased, making areas narrow. Bookshelves placed in each layer created ‘tight and claustrophobic spaces’. The freer flow of movement became turbulent, leading to a feeling of ‘confusion’.

Yet, Odong Library might have reflected more of human agency and free will, despite some confusion. If Hannae Library responded to a given programme in a defined space, Odong Library certainly had a ‘nomadic freedom’, a feeling created simply by having movable chairs allowing people to roam. Of course, there was some bias and restlessness as not all spots were equally good, with people tending to move to a spot by the east window whenever it became available.

I believe the charm of Unsangdong Architects lies in their ‘unique forms’ shaped by creative imagination. However, in the work of small-scale spaces that invite a physical response, I think the structure-space concept needs more delicate human sensibility alongside adaptability to the environment. I enjoyed this opportunity to examine the complex work of Unsangdong Architects.

Unsangdong Architects (Jang Yoongyoo, Shin Changh

Kim Bongkyun, Han Narye, Goh Youngdong, Lee Siyou

110-10, Hwarang-ro 13ga-gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul,

neighbourhood living facility (public library, ca

997.5m²

431.2m²

431.2m²

1F

2

5.5m

43.22%

43.22%

wooden structure

laminated timber, standing seam zinc roof, low-e

oil stain on wood, wood flooring, stone tile, car

Gumna Structure, SUPIA Construction

Kunyang MEC

Hyeobin Electrical Design

Wonha Construction

June 2020 – Dec. 2021

Dec. 2021 – Apr. 2023

Seongbuk-gu Office