SPACE December 2023 (No. 673)

[PROJECT] A Space of Relationships

Mauricio Pezo, Sofia von Ellrichshausen co-principals, Pezo von Ellrichshausen × Kim Jia

Kim Jia (Kim): Luna House is located in the foothills of the Andes in Chile. It is arranged horizontally around four courtyards on a site of approximately 5,600㎡.

Sofia von Ellrichshausen (Ellrichshausen): Luna House is a building divided by a series of seismic joints, which respond to the structural requirements of its horizontal extension. The seismic joints are composed of a 50mm separation, which appears like a slim cut, through the entire section of the building, from the foundation to the roof slab. These cuts separate the entire structure into twelve fragments.

Mauricio Pezo (Pezo): The building is indeed a horizontal extension, a large flat volume, like a compact and heavy plate resting on the ground. Within this form, there is discontinuity between mass and void, with large open spaces and very thin, wall-like volumes following the outer perimeter and an asymmetrical cross dividing its core. The spatial structure formed by such massing is equally asymmetrical.

Kim: Each courtyard features a unique landscape. What is the reason for breaking large-scale landscapes into small pieces through your architecture?

Ellrichshausen: I believe the building produces a very precise parting of the ways in the existing landscape. We understand nature, architecture included, as a limited set of things, of things with a limited set of attributes. The landscape has a particular geology, a particular geometry, fixed elements like rocks or trees, moving features like clouds or birds. But the landscape is the visual appearance of all of these elements combined; this is how we humans experience and give meaning to all aspects of a vista.

Pezo: That is why we would prefer to read the building as a form made from partition, as much as from demarcation, an interruption and obstruction of the existing landscape in order to reframe its profound internal spatial relationships. We would like to understand the building as ‘specific nature’; as a spatial system that becomes a framing device that substantiates, or unifies, the separate attributes of the landscape.

Kim: The building wrapping around the courtyard functions like a corridor. What kind of sequencing and spatial experiences did you intend to create?

Ellrichshausen: The building has a double nature. Seeing it as a whole, it occupies a substantial footprint of more than 5,000㎡. On closer inspection, the building itself is a linear sequence of narrow rooms, like a stripe format that increases the perimeter walls and their contact with the outdoors. In this sense, one could read it as a rather small building with a regular width of a little more than 5m. The consequence of such spatial configuration is a clear disproportion between indoor and outdoor rooms. This ratio is about 1:5, which means that only one fifth of the total volume is actually conditioned space. What is certain is that the size, orientation and proportion of the rooms, as much as their material consistency, bring about a new scale or measurement within this wilderness, a kind of imposed human order.

Kim: The interior space emphasises geometrical elements, as noted in the circular or rectangular openings and wall surfaces. What significance does geometry have in terms of function and form for this project?

Pezo: The openings on walls, floors or roofs were intended to offer singular moments of intensity. They are also meant to be articulation elements, which, in our view, should remain as discreet as possible in order to be disregarded while the articulation is happening. In other words, a square window shape, or 1:1 ratio, allows for view, light or ventilation, the three functions of a window, without interfering nor taking away our attention on those functions. The 1:1 ratio is perceived as an abstract figure. It does not suggest any figuration, any decoration, anything that might distract from the essential relationship. In opposition to a 1:1 ratio window, which does not communicate any scale unless a person is next to it, a 1:2 vertical opening already suggests a relationship with the human body, which is associated with the function of a door.

Ellrichshausen: We prefer to read architecture as a self-referential system of relationships. The elements that make those singular and special relationships possible, in our view, should be the opposite, this is; as blunt, nonspecific, and as unnoticeable as possible. The square perforation, as much as the circular ones, are governed by such characteristics. Their size and position are more important than their shape.

Kim: The sense of transition and tension created at the meeting point between the rectangles and the circles is also interesting.

Ellrichshausen: We are well aware of the perceptual weight of such formal definitions. There is a tension between the lines, planes and volumes that configure architectonic space. There is also a tension between a circular skylight and the rectangular corner formed by two walls, to the point that the wall might receive, literal and metaphorically, shifting qualities of daylight.

Pezo: If that kind of formal relationship can be conceptualised as object-object relation, there is also the object-human relation, which might be even considered an interference in the object-object direct relationship. Likewise, there is an object-living non-human relation, which are those walls, windows and columns featuring the hummingbirds, the roses or the oak trees. This system of relationships can be further extended. Thus, the formal attributes, like the simplicity of a geometric figure, are only one more factor within a dense and always changing system of relationships.

Kim: What are the intended programmes for each individual room?

Ellrichshausen: There are many rooms and many specific functions. While there are domestic quarters to sleep, cook and rest there are other areas to work with wood, to work with metal, to paint, to write or draw.

Pezo: Anyway, the functions of Luna House are both specifically and loosely defined. Since this is a place for team work, for the production of art and architecture, there are individual apartments, with their individual private courtyard, so as to guarantee the necessary levels of seclusion and intimacy. There are also some rooms for collective work and rooms for individual work. The boundaries between one domain and the other are not strictly drawn, thus the feeling of a continuous human landscape that fluctuates depending on the presence or absence of people.

Kim: You created a rich texture across the concrete surface by using wooden moulds. What particular kind of texture did you have in mind?

Ellrichshausen: The whole building is made out of in-situ reinforced concrete. We also knew that the building had to be strong and robust not only to withstand local earthquakes but also resist the potential forest fires that threaten the region.

Pezo: Apart from that sense of endurance, we were also aware of the fact that the building is remotely located. This made the technical aspects and logistics of supply and transport crucial. Therefore, we decided to incorporate a simple construction method that would allow both for efficiency and inefficiency. The construction system is based on the fact that we could only bring raw materials instead of elaborate products. This meant that we could bring steel rebars, cement, gravel, sand, plywood, lumber and nails or screws. If the concrete material and its rough surface express anything, I believe it might express its own geological nature. And by geological nature I mean its chemical, almost alchemical, property of mixing aggregate with cement and water, of being temporarily a fluid that solidifies over time. Within this materialistic description, I would also include human contact with inert matter. The whole building was made by hand, it is a large hand-made object. Therefore, its surfaces are filled with records of the human incapacity, a beautiful incapacity, to make thinks absolutely right.

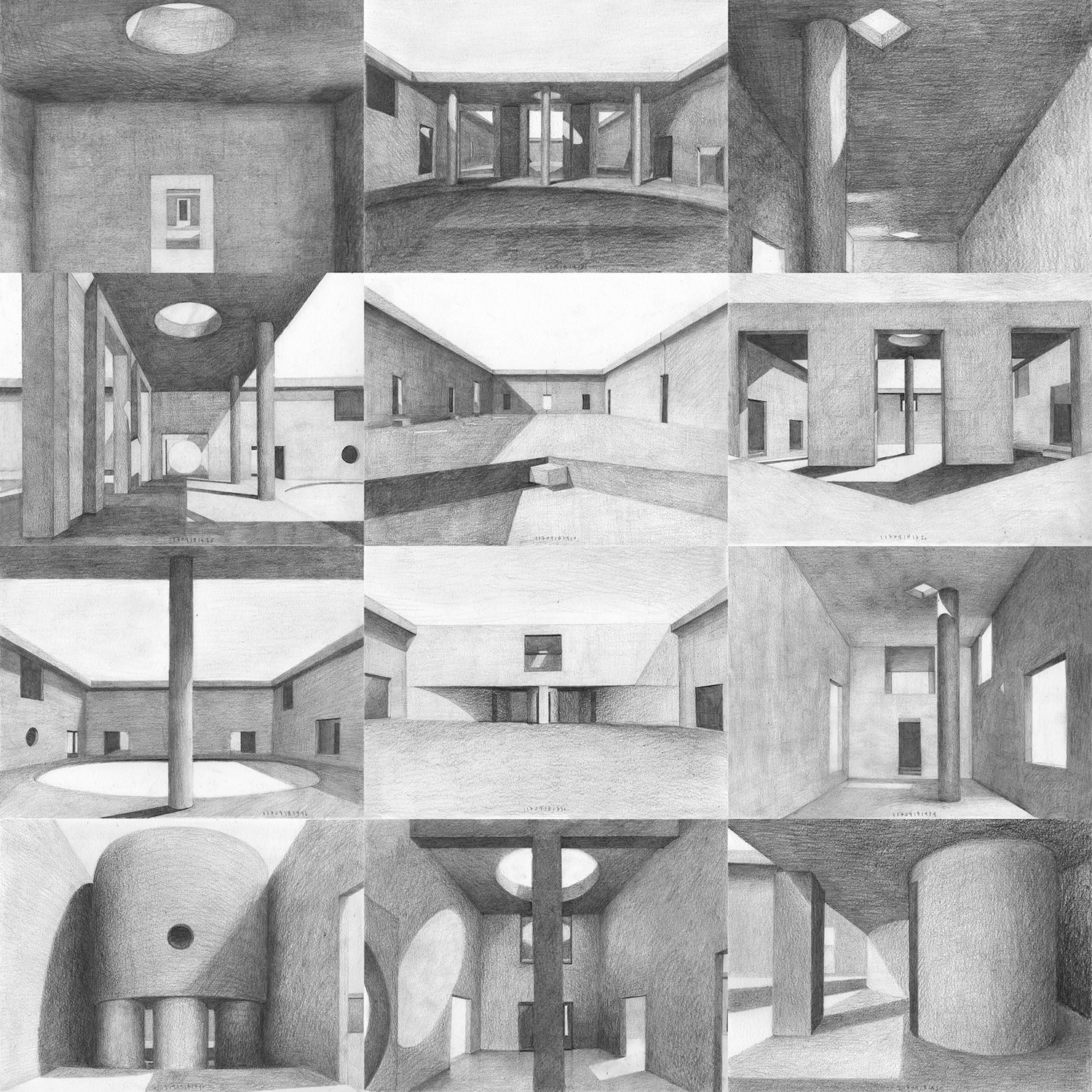

Kim: The sketches or drawings are also interesting. At which point in the design do these sketches get drawn and how do they come about?

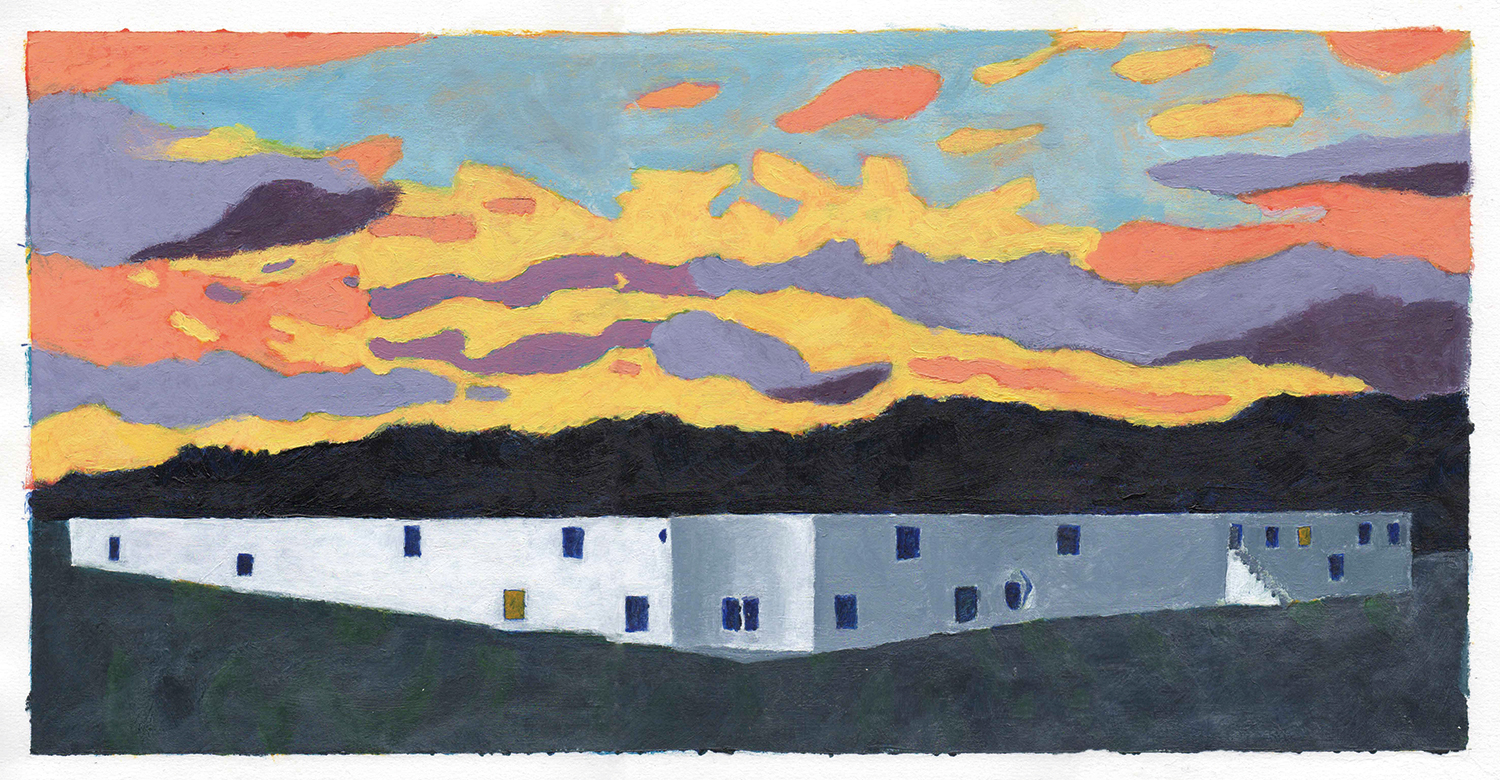

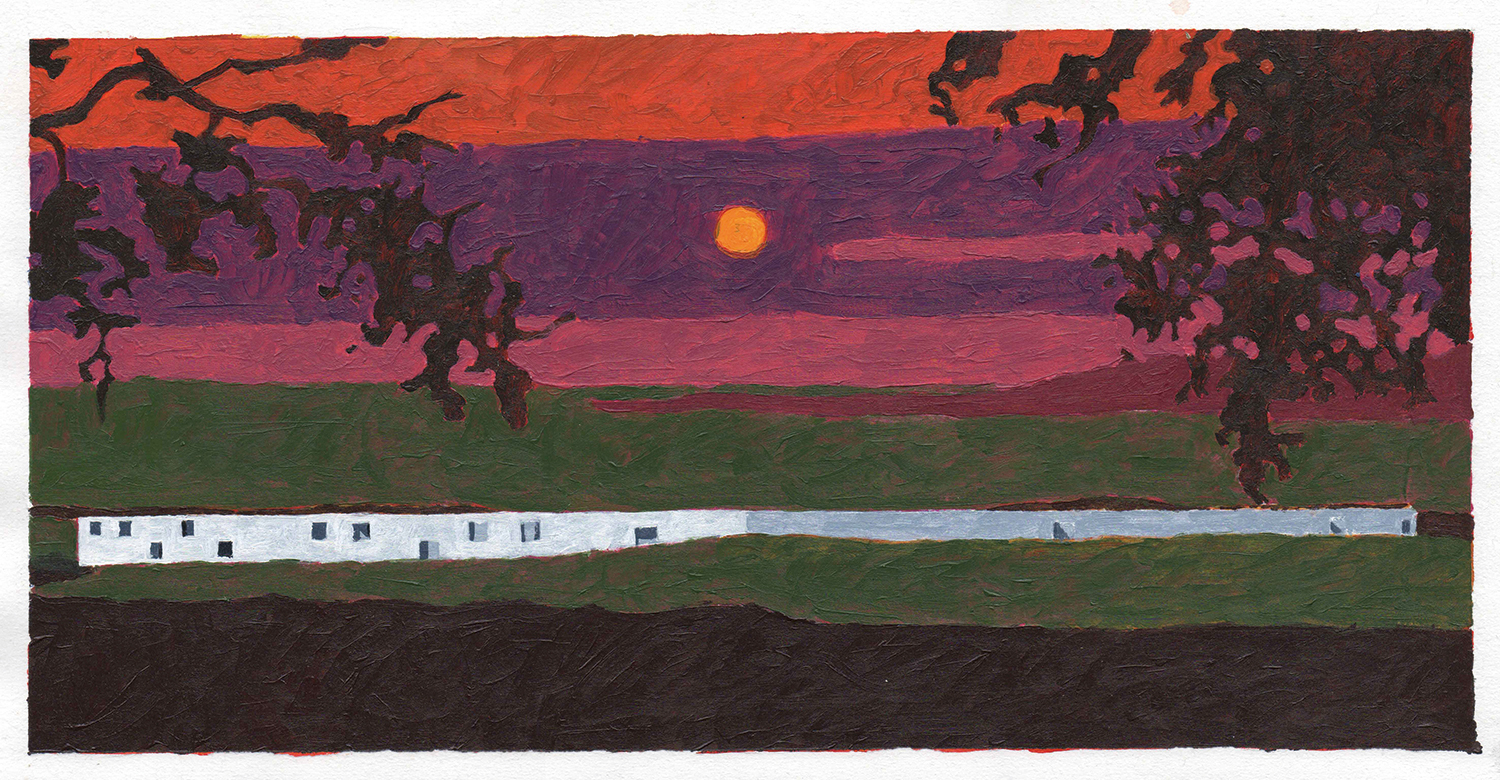

Ellrichshausen: Paintings and drawings are present during every stage of our conception process, from initial sketches to final editions. We employ many techniques, from simple ball pen line drawings to watercolour, graphite or acrylic on paper or more elaborate and larger scale oil on canvas. We prefer to do larger formats when buildings are under construction or even some years after their completion. We see the practice of painting as a constant exploration into the nature of architecture.

Pezo: We see it as a reciprocal activity. We strongly believe that hand-crafted representations of buildings are thinking tools. We do paintings or hand drawings as time machines, as devices that allow us to reflect slowly on what we are doing. It is not about efficiency or resolution, like the digital collages or hyper realistic digital renders. It is about seeing the world through a delicate lens when on the surface of the paper or canvas.

Kim: You have often emphasised the importance of incorporating architecture as a part of nature. How would you like to view the relationship between architecture and nature?

Pezo: We are extremely sensitive to the traditional distinction between architecture and nature. Of course, we agree that architecture is a work of artifice, a human product ruled by a degree of intentionality that the natural world simply does not possess. Regardless of this distinction, we also agree with current environmentalist philosophers who claim that the very notion of Nature, of that romantic domain with capital N, is today’s obstruction to a more genuinely and productive relationship with our planet. Nature shouldn’t just be the lake or mountain one sees through the window. Nature is everything physical, every process, every relationship formed within the world. Architecture is one more interrelating factor within the world.

Ellrichshausen: Instead of separation, or attending to a dialectics of positive-negative or resource-consumption, we would prefer to understand the production of buildings as one of ‘second nature’. This notion has a couple of connotations. First, it suggests that it is something that ‘becomes’ natural over time, a habit or skill that you have repeated so many times that you don’t think about anymore, like breathing or walking. Second, the notion of architecture as second nature suggests that a building shares the attributes of the ‘first nature’, the so-called given nature. Among other attributes, there is also an important degree of opacity, or inexhaustible depth, that we will never be able to unveil.

Pezo von Ellrichshausen (Mauricio Pezo, Sofia von

Santa Lucia Alto, Yungay, Chile

single house, gallery

5,000m²

2,400m²

2,400m²

RC

exposed concrete

exposed concrete

Sergio Contreras

Constructora Natural

2018 – 2021

2018 – 2021

Fundacion Artificial

Their work has been exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the MAXXI in Rome and as part of the Permanent Collection at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Carnegie Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. They have been invited to the Venice Biennale (2010, 2016), where they also were the curators for the Chilean Pavilion in 2008.