After the Desire for Redevelopment

After the announcement of the New Town Project in 2002, fantasies of development took over Seoul, and Jaegi district 5 was no different. Designated a redevelopment zone in 2006, it suffered the ups and downs of association formation and was only lifted from the redevelopment zone in 2018, more than a decade later. However, while the fantasy of redevelopment has been a source of desire, Jaegi district 5 has been subject to a process of rapid deterioration in urban space. The site of the project is located in the middle of Jaegi district 5, amongst urban spaces where time seems to have stood still.

The streets were too narrow for vehicles to pass through, and the 40m -long narrow path, surrounded by long- abandoned houses, had deteriorated to the point where it was troubling to walk at night. Although it is only about 200m from the main entrance to Korea University, it has become a place apparently frozen in time, far removed from the vibrancy of youth. After it was lifted from the redevelopment zone, large-scale redevelopment was cancelled, leaving room for individuals to improve the neighbourhood through gradual steps. Stores and restaurants for students began to open in the area. However, the site was a collection of plots of land, some as large as 100㎡ and others as small as 5㎡. At the time, organising the plots was a priority. By the time we joined the project, a total of 15 small plots had been combined into eight, but even the combined plots were too small to be planned individually. So we carefully proceeded on the planning of a new architectural process of integration and division through being a ‘collective’, hoping to bring the energy of daily life, as well as new stories, to this place where time has stood still.

|

|

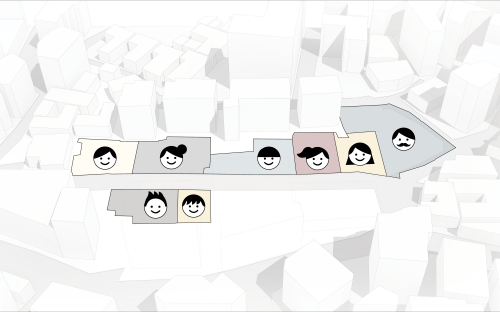

1. Eight plots, eight owners |

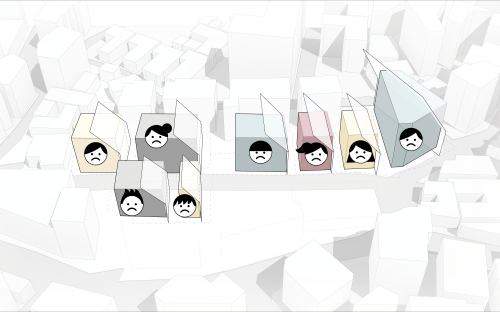

2. Each plots were too small to be planned individually. |

|

|

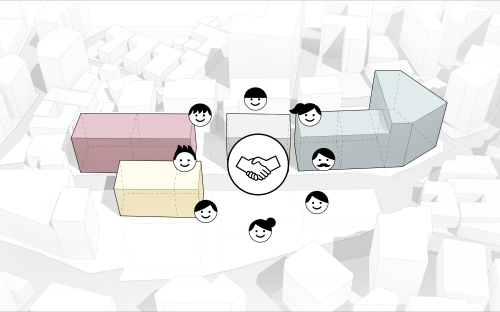

3. Through the agreement of the property owners, a new building type that used party-walls to divide the building plots was proposed. |

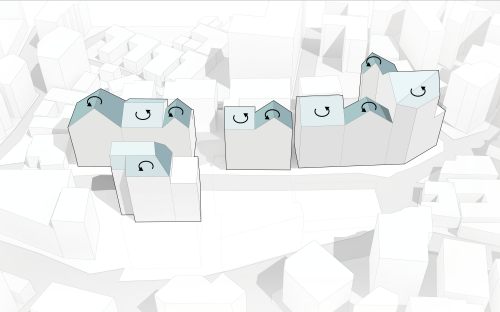

4-5. Variations were proposed in the form of roofs of each building. |

|

|

5. Variations were proposed in the form of various terraces on the upper floors of each building. |

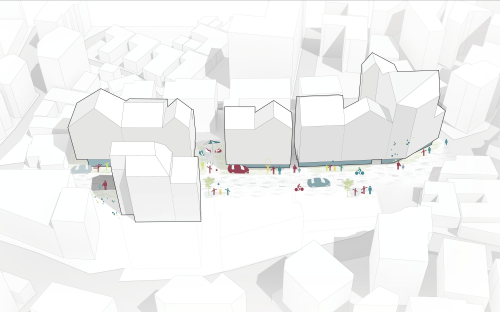

6. Collective-based construction process bring vibrant daily life and new stories to the path. |

A Collective Architecture

The challenge of the project was twofold: to create a residential space that suited the diverse lifestyles of young university students, and to create a new, vibrant urban space without overwhelming the urrounding urban environment. Being a collective, comprised of the eight property owners, we hoped to improve the unfavourable conditions of each plot and proposed a new method of urban regeneration within the policy framework of the Autonomous Housing Improvement Project. Autonomous Housing Improvement Project allows single-family houses, multi-family houses and terraced houses to be renovated or built together with their neighbours, and two or more landowners to form a resident collective to maintain dilapidated dwellings. The individual property owners of the eight plots formed a resident collective and consulted on everything from architectural plans to operating methods. The architects began their work by collecting and mediating between the different requests of each owner. Fortunately, during the difficult consultation process, the foundations for a new type of urban architecture were gradually formed.

First, it was necessary to secure a reasonable building area on each site. Since it was impossible to achieve an appropriate floor area ratio due to limits on heights of buildings for solar access, a new building type that used party-walls to divide the building plots – which was an unfamiliar architectural type in recent Korea – was proposed. The property owners agreed to allow their buildings to share a side wall. Through the new building type, the eight projects were integrated into four architectural groups, and variations were proposed in the form of alternating rotated roofs and various terraces on the upper floors of each building. This way, each plot was given a distinctive appearance, while the resulting interior spaces varied from building to building. Rather than using brick as the main exterior material, which would have lended in with the existing neighbouring buildings, brick colours were sequentially repeated to visually divide up the relatively volumes of the buildings.

The agreement of the residents was not only required to secure a reasonable building area. To make the front streets more active and pleasant, the resident collective agreed to a proposal to discourage parking in front of the buildings unless absolutely necessary. They also agreed to adopt an open plan that would allow everyone to pass freely between the front and back of each building without a fence between them, and to incorporate the surplus space on each plot into the urban space. The agreement continued throughout the construction process. Due to the narrow width of the front road, it was not possible to build on all eight plots simultaneously, so the task was to start with the innermost plots first. This more than doubled the construction time, but the resident collective proceeded with the project on an greement basis.

Such a collective-based construction process allowed for the individuality of each building and the diversity of its interiors to be taken into account, as well as the potential for the buildings to suitably integrate into the surrounding urban environment, all of which was decided in communication with the residents. The process of integrating and again dividing the eight plots was applied throughout the architectural process, not only in terms of architectural form, but also as a means of involving residents in consultation, imbuing the project with both coherence and diversity.

Coexistence and Participation

Today, more than 80 college students or young office workers live together in eight different projects on eight different plots. Each building consists of a different housing programme for a single person, either as a single-family house, a studio or a shared house, depending on the circumstances of the plot and the needs of the client. Each building also has different communal programmes, such as a communal kitchen, a roof garden and a communal study café. It was interesting to see how the different internal configurations of each building allowed residents to form relationships in different ways. The number of residents who make close relationships varied according to the floor and building configuration of the communal areas, and the location and condition of the communal kitchens also influenced the frequency with which residents participated in communal meals. Differences in built environments resulted in different levels of community involvement and intimacy, and different levels of self-imposed discipline.

The sequence of stores on the first floor of each building is one of the most important elements in making this urban space safer and more enjoyable. Currently, there are pop-up shops, bakery, light design studio, café, flower shop and more filling the street, all interconnected and contributing to the vitality of the street.

Urban Agency (Park Heechan, Henning Stüben) +

Kwon Minjae, Rosa Fuentes Fernandez, Scott Grbava

22 Anam-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea

multi-family house, neighbourhood living facility

1,004.55m²

564.76m²

2,110.42m2

B1, 4 – 5F

13

18m

56.22%

197.23%

RC

brick, coated metal, low-e double glass

epoxy resin, deco tile, paint

Solveit Engineering

Sunwha Engineering

MK Cheonghyo

Seoyang Enc, Siwoo Design Group

Dec. 2018 – Feb. 2020

Apr. 2020 – Jan. 2022

5.1 billion KRW

8 individual owners

SLOWPHARMACY