SPACE January 2024 (No. 674)

Arbel Omer principal, Omer Arbel Office x Park Jiyoun

Park Jiyoun (Park): You appear to have sought to create harmony between this 740m2 house and the vast farm and grasslands site located in northwest Canada by using an embankment and organically-formed concrete in the interior and exterior. What were your first impressions of the site, and how did you begin to shape a connection between this landscape and your building?

Omer Arbel (Arbel): We had to develop an attitude to the horizon and to the sunset. We felt we had to build our section to turn the gaze upwards or downwards, devise a break, if you will, from the endlessly extending horizon at least sometimes. The site is essentially flat and has a very high water table, which made excavation impossible. We did this by considering the agricultural field a fabric, as if it were a giant carpet, and drew it over the house. We also considered the concrete pillar forms as giant planters with mature trees in them, punctuating the natural topography with their upward aspect. We explored the possibilities for the interior architecture by varying the height of these concrete forms, suggesting a choreography between both circulation and sight lines, always passing below or above a sculptural form and always in relation to a graphic foreground, midground, and background.

Park: Ten concrete pillars resembling trees can be found in the interior. What structural, functional, and aesthetic purposes do these pillars have?

Arbel: The concrete forms resulted from experimentation with fabric formwork. They serve equally as the main structural component in the house (amazingly slender for an earthquake risk zone), as planters for mature trees on the roof, and as expressive forms delineating a cadence of movement within the interior.

Park: The pillars are made using custom-made fabric formwork. How does this differ from general formwork?

Arbel: We used a woven geotextile stretched between plywood ribs arranged in a radial pattern to make the pillars, and poured concrete into them very slowly. The formula for the concrete was such that it began to partially cure at more or less the same rate as the pour so there was never too much stress placed on the fabrics. The result was a supple form that more or less followed efficient structural lines, resulting in a significant reduction in the amount of concrete, steel, and labour required, as well as the waste or downcycling associated with conventional formwork. Importantly, the concrete forms are a direct result of the process of making, honest to the material’s intrinsic fluid dynamic properties.

Park: What experiments did you perform to create the desired shape of the fabric formwork?

Arbel: We worked with our structural engineers Fast + Epp and our Build Wright Construction to develop the fabric forming method, using as our starting point the theoretical work published by Mark West of the University of Manitoba, and augmenting it by making half-scale and then full-scale prototypes. The method included developing a novel recipe for the concrete, a design for the formwork, and a deliberately slow schedule for the pour. The largest of the concrete forms is about 10m tall, which is, in conventional circumstances, too tall for a single concrete pour. In our case, however, it was impossible to suggest pouring in several ‘lifts’, with each curing before the next is introduced, as is common in concrete construction. This is because if a first layer of concrete is allowed to cure, and then a second can be introduced. The liquid concrete from the second pour finds its way between the cured concrete from the first pour and the fabric, it can result in spalling. As such we needed a way of casting very large monolithic forms in one continuous pour. The result was to pour concrete at a rate that closely matched the cure rate, roughly 1.2m per hour.

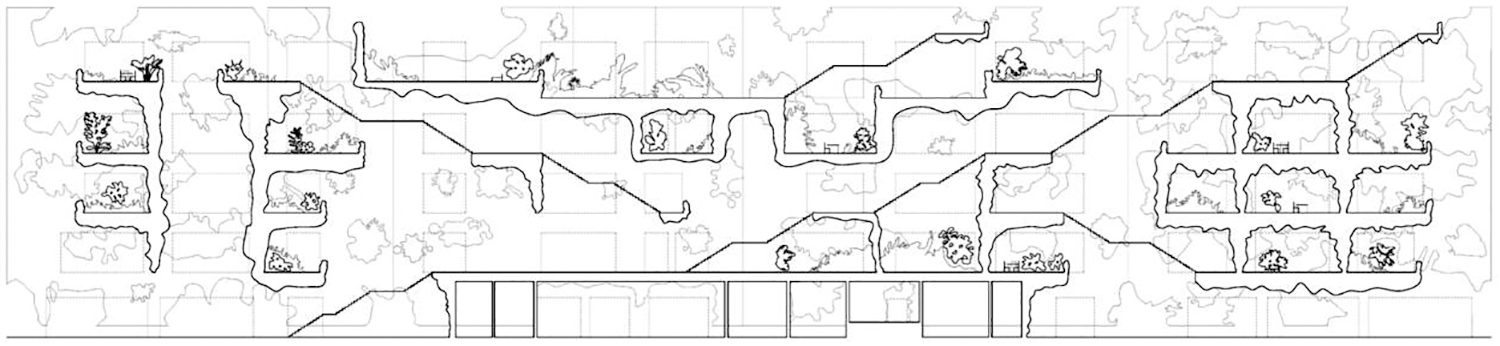

Section proposal of 86.3 using fabric/hay formwork

Park: Considering that you are using a wet method that creates a unique form, the site conditions must have been critical. How did you deal with unexpected discrepancies between the plan and on-site work?

Arbel: The method was designed to be quite loose. We wanted to allow a lot of latitude for the material to express itself during the pour because it was important to us that the forms resulted not only from our method, but also informed by all the circumstances and contingencies of that moment in time; the people working on it, the site, and even the weather. We wanted to be surprised by the results, and we were! Surprised and delighted.

Park: What discernible difference is there between the fabric/hay formwork used in your office project 86.3 (2019 –) and the present fabric formwork? What led you to come up with the newer version?

Arbel: The fabric formwork has been stretched between ribs, so my team were still able to exert quite a lot of control over the forms. We decided where to position the ribs and what form they would take. The hay bale idea was an attempt to relinquish a little of this control. We hope to be met with even more surprises when we remove the forms. It is important to say that 86.3 is still at the prototyping stage, so images of the prototypes are not representative of the final forms we hope to achieve.

Park: Thus far, your means of adding expression to concrete have mostly been accomplished by adding textured finishes via pattern formwork. What makes concrete interesting as part of a morphological experiment?

Arbel: I think of it as a contemporary take on humanism. In a world increasingly dominated by parametric technologies and increasingly sophisticated modeling software (and soon by AI) anything at all that can be imagined, will be possible to build, given enough resources. In such a world, in which any form at all is theoretically possible, I ask, what forms are most appropriate? What forms are good? For me, there is a satisfactory answer lodged in forms that are born of a material’s intrinsic properties and those that emerge in the process of making. The architect works as a collaborator with their materials, methods, and collaborators, not as a dictator. I realise this is perhaps considered nostalgic or romantic, or both.

Park: You have created unique forms by using materials such as copper, glass, and concrete in your products, sculptural forms, and architectural works. How does opening yourself to various materials and forms across these diverse areas shape your working style and ambitions?

Arbel: My methods do not influence the work, they are the work.

Omer Arbel Office (Omer Arbel)

Mark Dennis, Kathryn Lamoureux, Jaedan Leimert, G

Vancouver, Canada

single house

740m²

RC

concrete

wood

Fast + Epp (Thomas Duke, Nick de Ridder)

Build Wright Construction

2017 – 2018

2018 – 2023

JRS Engineering

Bruce Gernon Architect

Treeline Construction