Architecture in Favour of Life

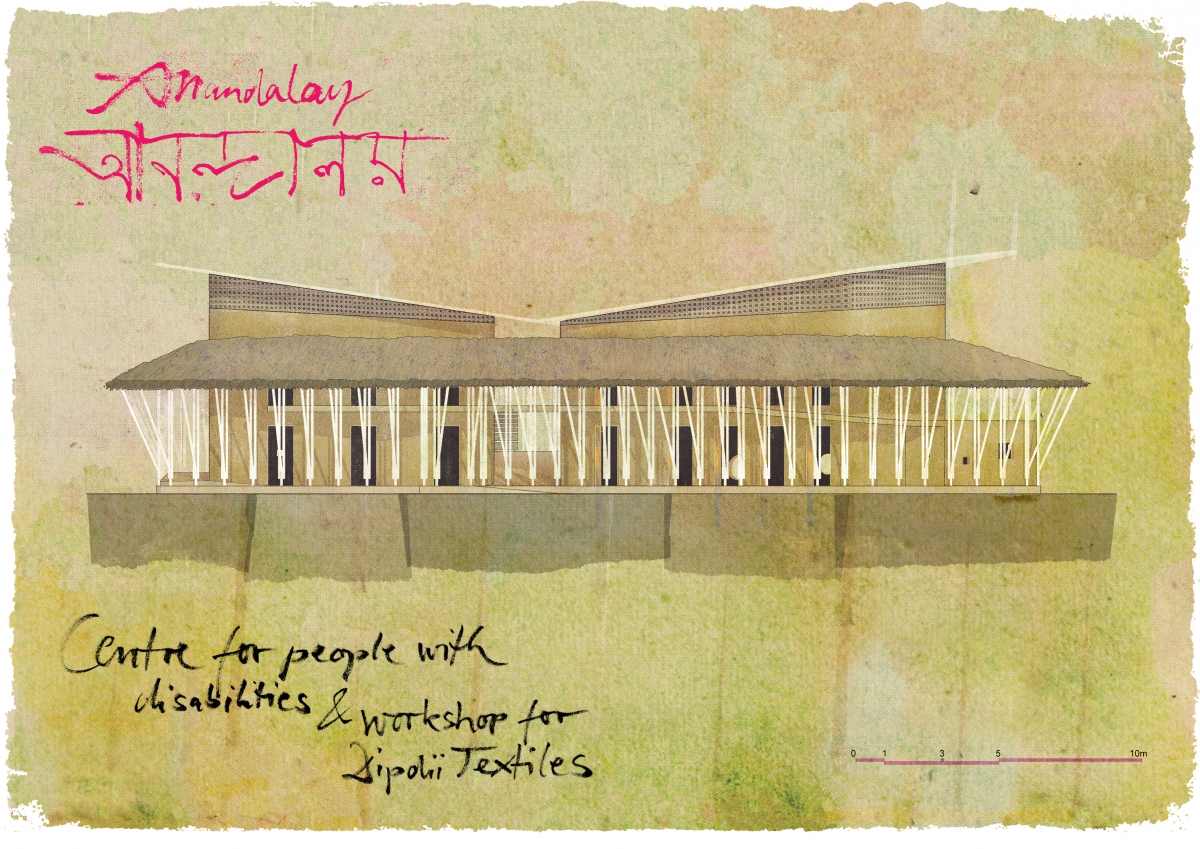

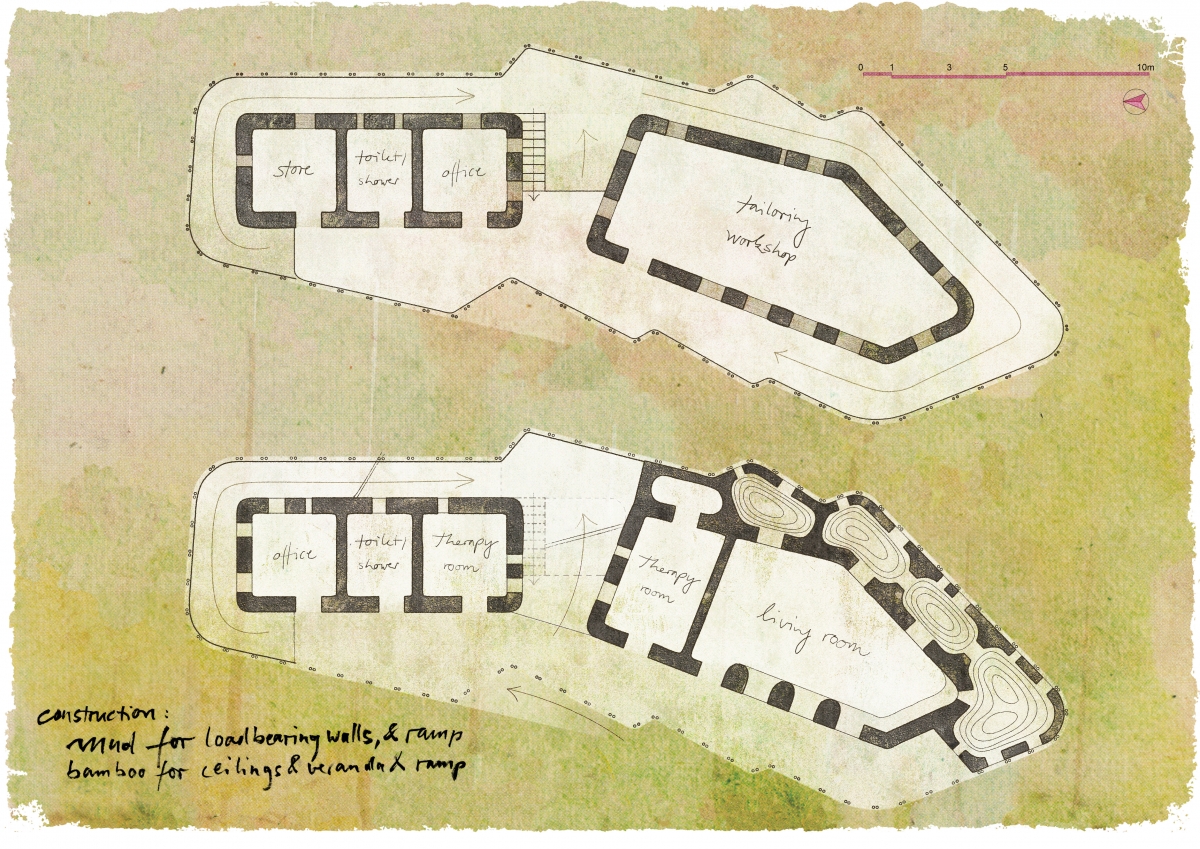

Surrounded by lush green paddy fields in northern Bangladesh stands a curved building of two-storeys built from mud and bamboo. The mud walls twist, while a ramp winds up to the first floor. Below the ramp are caves that provide either entertainment or repose. The building is called ‘Anandaloy’, which means ‘The Place of Deep Joy’ in Bengali. This unconventional, multifunctional building is host to a therapy centre for people with disabilities on the ground floor and a textile studio on the top floor which produces fair fashion and art.

Celebrating Diversity and Inclusion

In Bangladesh, disabilities are viewed as great burdens from god or as a karmic afflication from a previous life. There is little awareness in the disabled community of imprvemebts to quality of life, such as training, massage, and therapeutic equipment. The therapy centre helps them in this respect. Furthermore, the provision of their own space as one not separate from those using the top floor lends dignity. What I want to communicate through this project is that there is beauty in not following the standard pattern. I do not follow a typical rectangular layout; the building dances, and dancing beside it is the encircling ramp. That ramp is essential, because it is a symbol of inclusion. It is the only ramp in the area, and as the building’s most noticeable feature, it triggers questions. During construction, it was topic of discussion between local visitors to the site: What is the reason for that ramp? Why is it important to guarantee access to everyone? How can the lives of people with disabilities be improved? How can greater accessibility be incorporated? In that way, the architecture itself raises awareness of the importance of inclusion. Diversity is something to celebrate.

Women and Textile Studio

Women in rural Bangladesh have few work opportunities. Many of them move to the city to live and work in factories under inhumane conditions. I wanted to give them a chance to earn their own living in the village, where they can make use of their own resources, build their own houses with their hands, grow their own food, and take care of their families. So I open the fair textile studio, Dipdii Textiles. That is a clothes-making project for local women that Veronika Lang and I launched with the NGO Dipshikha to support local textile traditions and to improve work opportunities in the village. We donʼt just build and leave a building behind like other architects, we are in charge of the programme inside the building. The project pushes the boundaries of my work. I see myself very much as an architect but also as an activist. (written by Anna Heringer / edited by Bang Yukyung)

ⓒKurt Hoerbst

ⓒKurt Hoerbst

Building with Mud

I explored the plastic abilities of mud in order to create a stronger identity in Anandaloy. Mud is regarded as poor and old-fashioned material and inferior to brick, however, I think it is up to us to reveal its aesthetic potential through a contemporary approach. It is important to me to show that it is possible to build a modern two-storey house using simple resources. Mud is not just dirt — it is a building material of high quality that you can use to build very exact structures — not only small huts but also large engineering structures and even public buildings. With a particular mud technique called ‘Cob’ no formwork is needed, which means that curves are just as easy to make as straight walls. With its curves and complex geometry, the Anandaloy building is unique. It is our creative task to take an old material and make something suited to contemporary uses, needs, and aspirations. Mud buildings can be healthy, sustainable, humane, and beautiful. Clay is a material that truly enables inclusion. We had everyone working on site: young and old, able-bodied and physically impaired, men and women. It was wonderful to me that the workers created a structure on their own. Normally, they would wait to be told what to do, but with the construction of Anandaloy, they were completely engaged in finding their own solutions. It is not an easy building, with difficult geometry, but they did it, and when they showed me around the site, they radiated with pride. For me, that is the biggest reward: when the architect is no longer needed and techniques and know-how are embedded locally.

Sustainable Locality

With this building, everything comes together: local materials, local energy sources, and regional creativity. There are three things I valued at Anandaloy: first, that we can create something out of existing materials; the material below our feet and the things that grow around us are enough to make something beautiful. Secondly, Anandaloy is completely run through solar energy, and human labour and craftsmanship were also very important sources of energy in the project. And finally, inspiration for the design came from Bangladesh but also from beyond. For example, the façade adopts a Vienna weaving pattern, because the workers loved that design, and it was easy to apply with the local bamboo. I believe that creativity should not be limited, but that knowledge should travel and be accessible everywhere. Anandaloy is built to someday return to dust. I want to make decomposable buildings that leave no waste behind. We cannot see what the coming generations will need, but what I really want to remain is collective know-how.

ⓒAnna Heringer

ⓒKurt Hoerbst

ⓒStefano Mori

ⓒStefano Mori

Studio Anna Heringer (Anna Heringer)

Rudrapur, Dinajpur district, Bangladesh

communtity centre, therapy centre, textile worksho

253㎡

174㎡ (rooms), 180㎡ (ramp and veranda)

2F

masonry

mud walls (Cob technique), bamboo pillars (ceilin

mud walls, bamboo

Martin Rauch (earth and bamboo details), Andreas

Sep. 2017 ‒ 2019

Sep. 2018 ‒ Dec. 2019

Dipshikha Bangladesh

Stefano Mori