The Order Between Part and Whole

interview Zhu Pei principal, Studio Zhu-Pei × Choi Eunhwa

Choi Eunhwa (Choi): Jingdezhen, where the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum is located, has been home to the ceramics industry and culture for 1,700 years. Which regional haracteristics have your particular focus?

Zhu Pei (Zhu): Jingdezhen’s inhabitants live alongside the river, and build their workshops and houses to surround kilns. The city pattern has therefore been governed by the location and arrangement of the kilns, and a basic city unit is comprised of kilns, workshops, and homes. The city was packed with basic kiln units of various sizes, and narrow alleyways were squeezed in between the kilns to make room for the transport of porcelain by trolley to the riverside. Kilns also become known as a place for public communication in this urban space. In the old days, children would pick up a burning hot kiln brick on their way to school and put it inside their schoolbag to endure the freezing cold day. In summertime, when the kilns are temporarily closed, the cool wet air mean that they are wonderful retreat in which to play and socialise. It is clearly understood that the living memory of these kilns has been injected into the local bloodstream, and the image of their prototype lingers in the local mind. Naturally, they became a reference point for my design.

Choi: The composition of the museum space changes depending on the collection and exhibition in question. Unlike a typical art museum, which displays paintings, sculptures, installations, and video work, the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum focuses on ceramics, historical ruins related to the ceramics industry, and even ceramics architecture itself.

Zhu: If a question is posed to a piece of porcelain, ‘Where is your homeland?’, the answer would definitely be ‘a kiln!’ As such, the fundamental idea behind my design was to bring back a sense of homeland for these porcelain works. In fact, the scale of the museum in section is quite similar to the Xujia Kiln. Imagined scenes from our ancient past of craftsmen inside the kilns present themselves when a visitor observes the displays and passes through the museum. This is the desired so-called ‘rootedness’ in the past: it reshapes a past experience, and presents a kind of isomorphic inner life of the kiln-porcelain-human. In this way, new designs are combined with past experience.

©Tian Fangfang

Choi: Please explain more about the Xujia Kiln, the motif for the vault.

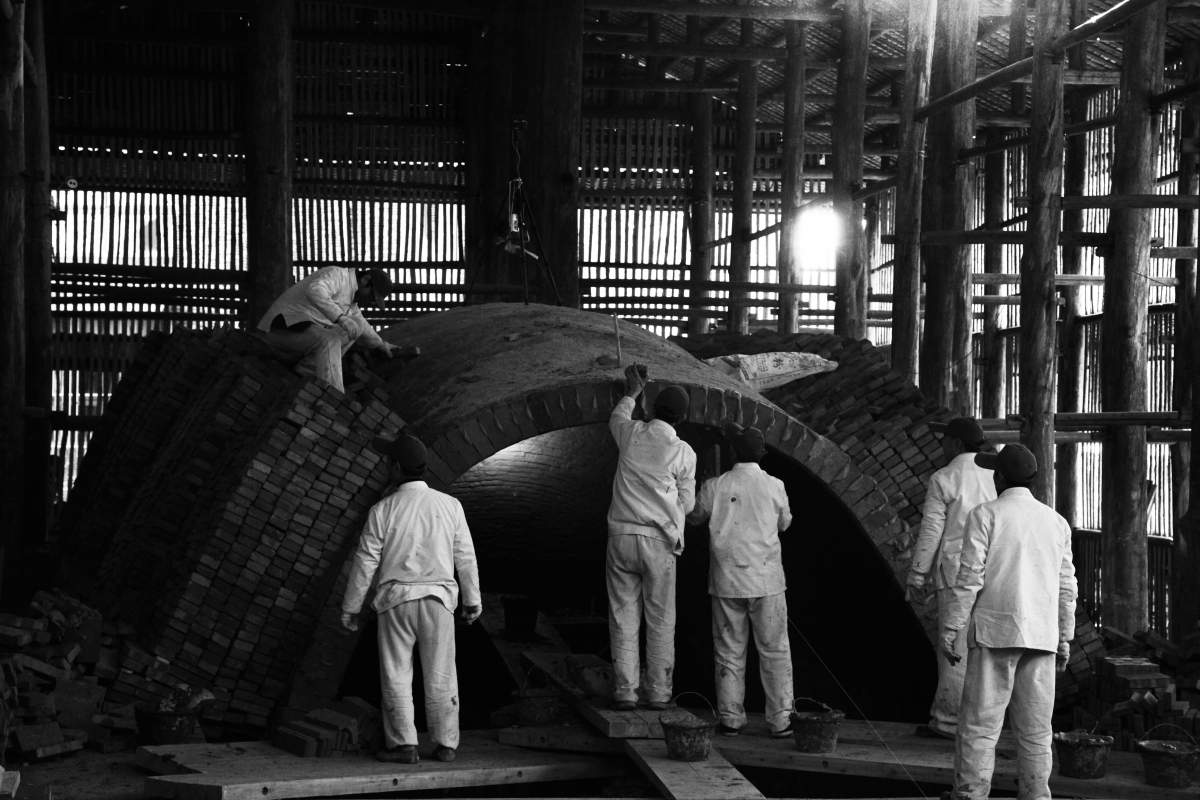

Zhu: When I began to conceive of this museum, the famed Xujia Kiln was by coincidence undergoing reconstruction. I am deeply attracted to the way the local masons build. The parabolic shape of kilns is made from light, thin clay bricks. No scaffolding is used, and the construction is carried out through the exploitation of gravity and the viscidity of clay. This vault, characterised as being of the East, fundamentally differs from that of the ancient Romans. As the inner air pressure is increased when the kiln is at work, a pre-calculated form by static mechanics probably leads to collapse due to the pressure difference. This is why in Jingdezhen not even a single intact semicircular vault can be found. All kilns have a more or less parabolic shape and shrink inside on both ends.

Choi: There are many options for construction and materials through which to realise the vault. What were your reasons for combining concrete and brick of your other various options?

Zhu: Self-supporting brick vaults such as Xujia Kiln cannot withstand the trembling of earthquakes. Reinforced concrete has to be added into the brick structure, thus turning it into a sort of ‘sandwich structure’. In fact, such methods had already matured by the time of the ancient Roman Empire. To construct fish-shaped hyperboloid surfaces by using the simplest system possible was the biggest challenge in the construction process. We researched and developed a 1.2m-wide sliding scaffolding system with the construction team. Adjustable metal bars – helped by this slight moving action – are placed to extend the scaffolding, and the entire formwork can be moved along a central track after each time the concrete is poured. The final hyperboloid surfaces are accomplished by such a method of flexibility. The bricks outside of the reinforced concrete were laid according to the local traditional masonry methods that we learned directly from Xujia Kiln.

Choi: You planned the museum space that is composed of segmented spaces with the vaults, instead of a single mega-size space. What is your intention?

Zhu: The design is quite well targeted, but deals ancient working with its relationship to the Imperial Kiln relics, the surrounding residences, and the newly discovered relics. Eight brick vaults of different sizes loosely form an arrangement that is not fixed – a loose connection to each other like the leaves falling to the ground in autumn – and they are embedded within this complicated site in a humble manner and on a proper scale. The essence of art exists between the status of being ‘like’ and ‘unlike’; it engages people with a feeling of familiarity and strangeness. An ambience of relaxation, of contingency, combined with a sense of handicraft, as well as being in the natural landscape, pervades the brick vaults and courtyards in between. The vaults – various in length, depth, height, and curvature – were placed informally and irregularly, which creates a strong but unspecified series of bonds that help them to integrate with and penetrate each other.

Choi: Finally, I’d like to know more about your intentions behind using two kinds of bricks: the new and the old.

Zhu: The older bricks were salvaged during the renovation of the old city, while the new bricks were produced in the traditional way in a brick factory in near region. It has long been a construction tradition in Jingdezhen to recycle kiln bricks. The ancient city was built using such recycled kiln bricks, everything from the houses to the pavements. A kiln has to be dismantled and reconstructed every one to two years due to the declining performance in the possible heat storage in the bricks, while the old bricks from the demolished kilns become a reliable source for the building of houses and the paving of streets. So, the old kiln bricks have long supported the cultural memories and urban life of Jingdezhen, and logically became the perfect material for our museum. When they, like those following the dismantlement of kilns, are later used to build houses or workshops, their DNA is preserved in the material. The whole of Jingdezhen has been built upon these as foundation, so their character is necessarily used and transformed in this new design.

Image courtesy of Studio Zhu-Pei

Studio Zhu-Pei (Zhu Pei)

You Changchen, Han Mo, He Fan, Shuhei Nakamura, Li

Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, China

exhibition, auditorium, amphitheater, multi-functi

9,752㎡

2,920㎡

10,370㎡

B2, 1F

9m

29.4%

106%

reinforced concrete arch shell, brick arch

old and new kiln brick masonry

wood, carpet, granite stone

Architectural Design and Research Institute of Tsi

Architectural Design and Research Institute of Tsi

China Construction First Group Corporation Limited

2016 – 2017

2017 – 2020

Jingdezhen Municipal Bureau of Culture Radio Telev

Studio Zhu-Pei, Architectural Design and Research