A Way to Contemplating Ruins

Zhu Qipeng (co-principal, Wonder Architects) × Lee Sungje

Lee Sungje (Lee): In your project statement you note that ‘Beginning in the winter of 2018, several architects successively built houses in a village on the outskirts of Beijing. This is one of them’. We want to learn more about the background to this project.

Zhu Qipeng: Our client was a couple that run a B&B in the village. As far as I know, they have dozens of courtyard houses (院落) in this village and in the surrounding villages, all of which operate as B&Bs. They negotiated with the villagers and rented their yards. The local government obviously supported this new business venture, which brought many opportunities to the local tourism industry. After operating for a period of time, our client desired the B&B experience they provide to be more artistic and attractive, so they hired some independent architects to design some new courtyard houses. The first batch was from five architects, including me. All five of us are architects with a certain level of experience, and we have relatively mature works in our profiles. Therefore, the client placed fewer restrictions on our design. But, as a B&B, there were certain restrictions placed upon us concerning the number of rooms and the construction costs.

Lee: We want to learn more about the project site and its surrounding environment, Houheilongmiao, which is one of the hundreds of Great Wall Guarding Stations built in the fifteenth-century.

Zhu: Houheilongmiao Village is located in Yanqing District of Beijing, in the mountainous region more than 70km north of Beijing. In 2007, there were 180 families in the village, and the population has declined in recent years. Ten years ago, the main industry of the village was dairy farming, which brought a lot of wealth to the village. However, due to increased environmental pollution, the dairy farm was forced to close. Now the village is mainly engaged in grape cultivation. As the village is very close to Guanting Reservoir, tourism has in recent years become one of its main industries.

The Great Wall is located 18km from the village. Unlike the image in most people’s imaginations, the Great Wall is not just a wall. The Great Wall is actually a huge defense system, especially the sections of the Great Wall surrounding Beijing. In the area, tens of kilometres outside the main city wall, there are also several lines of defense. These lines of defense include not only military installations, but also camps where soldiers are stationed, and agricultural areas where some soldiers are engaged in reclamation and production. When the Great Wall lost its major role as a line of defense, its interred soldiers gradually became farmers.

There are many villages like this around Beijing. The garrison strongholds and reclaimed farmhouses along the Great Wall defense line were later transformed into various settlements. Some villages still relate to historical sites today. In comparison, the historical remains of the Houheilongmiao are minimal, and so it has become a modern village.

Lee: Your project is an attempt to rebuild dilapidated houses. Looking at the photos you sent me, it seems that there are many ordinary cottages of this type throughout the village.

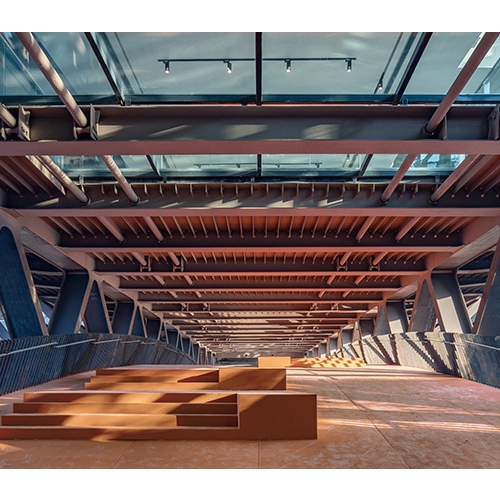

Zhu: Ruins used to be very common in the village, but now they are very rare. The main body of this kind of house was a wooden structure, with walls made of adobe bricks, and a roof laid with tiles. The building is divided into three rooms, with a hall in the middle and two bedrooms on both sides. There was a kang (?) in the bedroom, which is a bed can be heated in winter. From the fifteenth-century to the 1970s, the construction of such houses had not changed much. The building in our project should have been built in the early twentieth-century, but there may have been buildings of similar appearance already here.

At the time, this was a courtyard. Except for the structure we kept, there should have been east and west rooms, and a wall outside. Among them, the remains of the surrounding wall stand to this day. When we were building new houses, we excavated the foundations and found a very thick coal seam under the west side of the old house, which also proves something of the lifestyle of that time. The family that owns this old house may not be considered wealthy, as affluent families may use thicker wood and blue bricks. However, there is no doubt that the lifestyle represented by this old house offers a window into what was once the most typical lifestyle.

Lee: Your project literally embraces the ruined part of the collapsed house. And as your statement details, ‘After its completion, it still seemed to be a ruin surrounded by brick walls. I feel that our purpose has been achieved.’ I want to hear more about your thoughts on this project and about the deserted house.

Zhu: When we first saw this site, we were fascinated by the environment of the base. It is not flat ground, but a ruin that has collapsed. The original living spaces and traces left in the ruins are faintly visible. The trees in the courtyard are still growing. All of this was very touching. China is a rapidly developing country, the appearance of cities and villages is also changing rapidly. The scene reflected in the ruins is both familiar and strange to us.

They are not just spaces, but contain a record of previous lives. In such a place, you seem to be talking with the life of the past, which gives this scene value. Therefore, we try to preserve these historical traces in the new building, so that the remains of the old building can coexist harmoniously with the new construction and grow together.

Lee: I assume that your intention ― leaving the ruins intact ― was difficult for the public and the client to understand. What was the reaction of the client to this project?

Zhu: Our client didn’t understand why we kept the ruins at first, but when we showed them the renders, they quickly agreed. I believe that similar life experiences give them a sense of what we want to express. The biggest difficulty emerges in the construction process; workers do not understand why a seemingly unremarkable, broken house should remain part of the new building. They kept asking us during the construction process, and we had to constantly explain our strategy, including what to keep and how to keep it. It is gratifying that when the building was complete, most visitors understood our intentions. Our space talks.

Lee: As you noted in your previous answer, kang ― once the most important living space in northern North China, for thousands of years ― was introduced in this project. Why?

Zhu: Kang is a bed made of brick or adobe, featuring primarily in the bedroom. There is a flue inside the kang, which is connected to the stove. You can warm the kang by a setting fire in the stove to help people through the cold winter nights. As far as I know, there are similar facilities in traditional Korean architecture. The kang is much larger than the current bed area, sometimes accounting for half of the house area. Therefore, in addition to sleeping, many activities such as eating and entertainment can be performed on kang.

As a characteristic, kang has more possibility than a bed. And as a living pattern generated under a special climate environment, kang can exist for thousands of years and so it must have its own rationality. I have designed kang-like facilities in every bedroom. Although the new heating system has replaced the stove, kang, as a special living place, has survived in the new building.

Lee: China is experiencing rapid urbanisation and a modernisation. I surmise that the Kang has been significantly transformed or even disappeared at points overt the course of its history?

Zhu: Kang has a history of more than 1,000 years. In the agricultural era, kang is the most important way for northern residents to resist the harshness of winter. Whether in the countryside or in the city, ordinary people or the court, Kang was once in all of our homes. The disappearance of kang is mainly as it was challenged by new modern methods; a more efficient heating stove was introduced into China, in the early twentieth-century. For ordinary residents, kang occupies too much space indoors, and burning and cleaning can be troublesome. Many families dismantled Kang and changed to Western-style furniture. To this day, there are almost no kang in the countryside. For heating purposes, it is reasonable for the kang to be eliminated, but the living style provided by kang is worthy of our attention. A gratuitously retro approach doesn't make much sense, but in some instances the restoration of a special space presents greater choice in terms of lifestyle.

Lee: There have been many heated discussions regarding the presence of ruins in modern Western architecture. Modernism architects such as Louis Kahn and Le Corbusier often referred to the ruin when they explained the theory behind their architectural works. However, in Far East Asian architecture the wooden structure, which plays a more integral part in the architectural tradition, does not usually leave much of an imprint or trace once torn down, leading to few discourses on these ruins. I would like to know if there is a theory or discourse behind the ruins of modern or traditional Chinese architecture?

Zhu: The Chinese tradition does not value the aesthetic of the ruins. Villagers assume that after the destruction of gorgeous buildings, the land will become a new field or even wilderness, which is more beautiful; so many poems describe this scenery. On the other hand, Chinese people do set up monuments to mark monumental or significant places of historic interest. They will even rebuild a completely new building in a new way to replace those lost on historical sites. Unlike those in the West, there are almost no depictions of ruins in traditional Chinese painting, and they never seem to be regarded as aesthetic objects. This absence has deeply influenced the Chinese today. In China, architects often face their cultural heritage directly, because we are in the process of rapid urbanisation. Renovating old spaces and creating new spaces are problems that a large number of architects will encounter. China’s history is rich, but not all are strictly protected. This requires architects who can control the fate of heritage sites to be more careful and serious, because once historical heritage is destroyed, it cannot be recovered. Strictly speaking, the old house in ‘embracing the Ruins’ is not a valuable heritage site, but it is quite important as a carrier through which to inherit local memory. We also hope that an attitude towards cherishing history can become a consensus among architects.

Lee: Lastly, what are the issues nowadays faced by ICOMOS China or Chinese architectural society dealing with architectural heritage?

Zhu: The main problem we face is how to identify historical heritage in the construction process; which ones need protection and which ones are less important. The historical heritage included in the protection category is relatively limited; a lot of historical heritage sites are not considered worth recording. We do not need to accept them all, nor can we treat them as utterly useless things, but this requires some standardisation and consensus. When consensus is established, the value of some very precious things will be recognised by more people.

In China, another problem we face is the technology of protection. The protection of historical heritage sites, architectural design and construction are all different specialties. Many architects have a sense of protection, but most of them do not understand the protection methods and techniques, so they cannot guide their workers to take the correct measures. There is a term in the industry called ‘damage by repair’ (修?性破?), which refers to the destruction of historical heritage due to the misuse or neglect of protection technologies. Of course, we also hope to cooperate with a professional historical heritage protection team, and the architect itself also needs to have basic technical knowledge for protection.

In general, the protection of historical heritage sites is not only a cause limited to that of professionals but it is also a wider goal for the population. Architects as a group, in close contact with historical heritage institutions and bodies, can become an important force, but the protection process must be professional and rooted in highly advanced technical guidance.

Wonder Architects

Zhu Qipeng, Jin Tailin, Yuan Yingzi

Yanqing, Beijing, China

homestay

350m2

200m2

200m2

1F

4.4m

57%

57%

masonry

brick

brick, coating

Gao Xuemei

Wang Weiwei, Zhen Qin

Guo Chen

Wang Gensheng’s team, etc.

Mar. – Apr. 2018

Mar. – May 2019

Da Yin Yu Shi B&B