SPACE May 2025 (No. 690)

Exterior view of Goam Academy ©Lee Ungno Museum

Goam Seobang ©Choi BoYoung

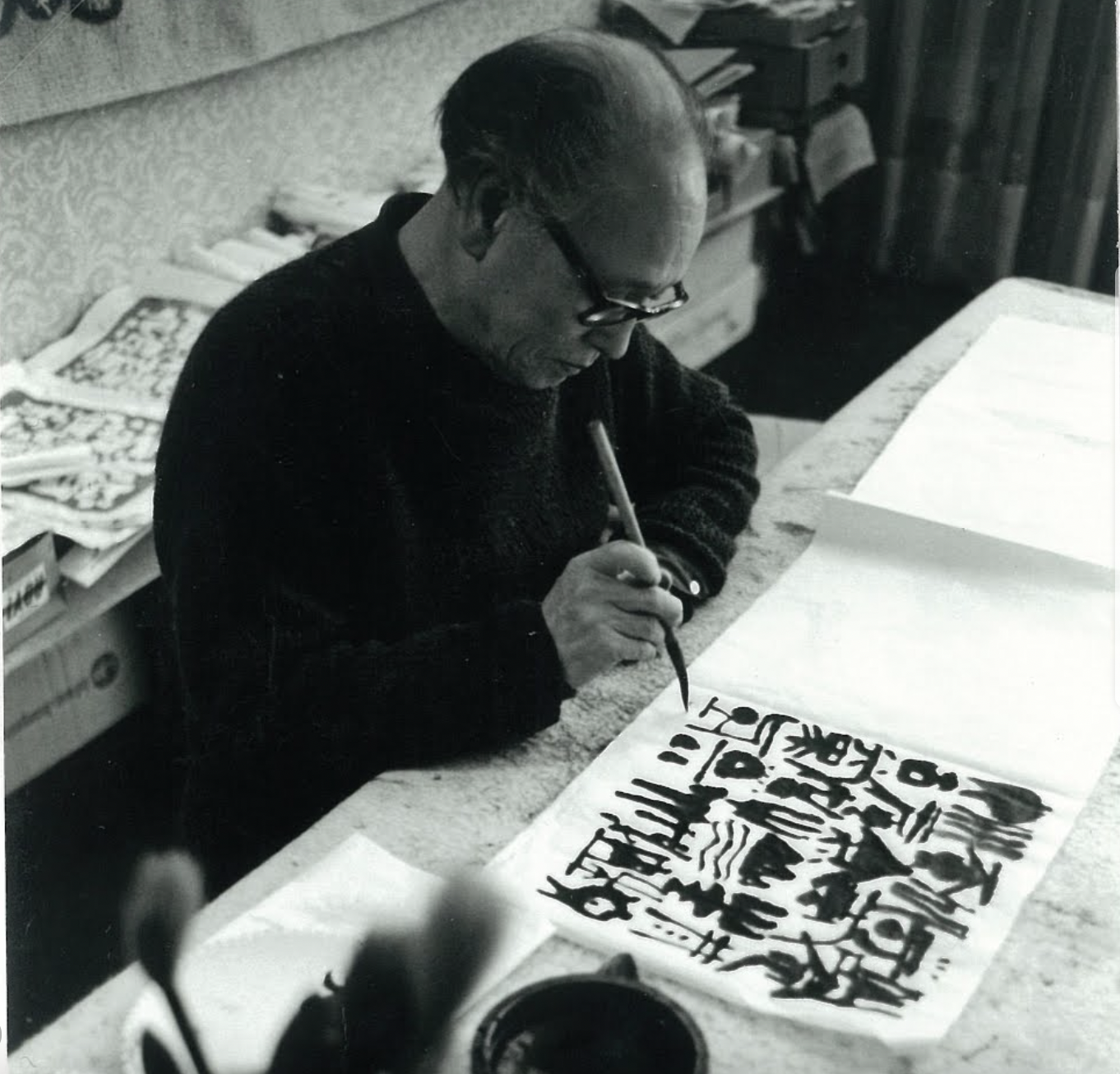

Scene of Lee Ungno at work on a painting ©Galerie Vazieux

Today, traces of the artistic legacy of Goam Lee Ungno (1904 – 1989), a master in modern Korean art, can be discovered throughout France. From the numerous works created when he was a member of the École de Paris, to the mural he created on Rue du Pré-Saint-Gervais where his last atelier was located, to the students he taught at the Academy of Oriental Painting in Paris (Académie de Peinture Orientale de Paris), to the Goam Cultural Heritage complex; his presence is deeply felt and woven within the cultural fabric of the country. The Goam Cultural Heritage Complex, in Vaux-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, is operated by his wife, the artist Park In-kyung, and son Lee Young-sé. It has served not only as a lecture venue for the Academy of Oriental Painting in Paris, but also as an important platform for introducing Korean ink wash painting to France.

The complex consists of five buildings: Goam Atelier (presumed to date back to the mid-nineteenth century), Lee Ungno Residence in Paris (mid-to-late twentieth century), Goam Seobang (1992), Studio of Park In-kyung (2008), and Goam Academy (2014). These five buildings are scattered across a hill that overlooks the Seine River, harmoniously integrated with the surrounding natural landscape. Among them, Goam Seobang, designed by master artisan Shin Younghoon, is particularly well-known as the first hanok constructed in France. The entire structure was initially built and disassembled in Korea, then it was shipped and reassembled in France. This fact meant that all the elements, except for the main beam, were from Korea. During the reassembly of the hanok, a sloped hill was chosen for the site to offer a panoramic view of the Seine River and Vaux-sur-Seine. Another architectural highlight is the Goam Academy, designed by French architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte. In dialogue with the adjacent Goam Seobang, Wilmotte used modern materials, such as concrete and steel to create a contrast with the more traditional material, the wood of Goam Seobang, and designed its tilted roof in reference to traditional Korean roof tiles. From an aerial view, one is able to observe that the building takes a form of a cross. The building’s cross-shaped footprint recalls Lee Ungno’s aesthetic vision of harmony and integration. The studio of Park In-kyung, known as ‘Wilmotte’s House’, was originally built for security guards. Later, Wilmotte renovated and expanded it over a year to serve as her personal residence and creative studio. In Goam Atelier, a nineteenth-century masonry house, Lee Youngsé continues his work as a painter. Meanwhile, the Paris Lee Ungno Residence, transformed from a former garage, has been operated as a vibrant artist residency for emerging Korean artists in collaboration with the Lee Ungno Museum in Daejeon since 2014.

How did a Korean modernist artist come to have such an impact on the French art scene? In 1958, Lee Ungno moved to France with his wife and son, leaving behind the chaos of post-war Korea to broaden his artistic horizons. Despite his roots in East Asian painting, he believed that it was more crucial for him to engage with the Western art than to remain in Asia. France, then the centre of avant-garde art, became fertile ground for new experimentation. In France, he began to develop his own distinctive visual language through creating collage that combined traditional materials like ink, hanji and objects such as discarded magazines. In contrast, Park In-kyung remained faithful to East Asian materials while embracing Western artistic techniques, including pointillism, informel, and colour field abstraction. Her style matured in the 1960s, as she began to fuse traditional ink with modern method such as bal-muk (the ink-spread method), dripping, pouring, and decalcomania, ultimately developing own unique visual language of ink wash abstraction. While participating in the dominant modernist movements of the time, the couple maintained their identities and together developed a distinct and independent aesthetic of Korean abstraction. The impact extended beyond the canvas. In 1964, Lee Ungno co-founded the Academy of Oriental Painting in Paris (Académie de Peinture Orientale de Paris) at the Museum Cernuschi in Paris with former director Vadim Elisseeff. There, he taught traditional East Asian painting techniques including sagunja, calligraphy, landscape painting, and flower-and-bird painting. The school nurtured a generation of French students and left an enduring impression on the French art community.

To celebrate the 120th anniversary of Lee Ungno’s birth in 2024, and ahead of Park In-kyung’s 100th birthday in 2026, Galerie Vazieux Paris in association with Lee Young-sé has organised a special exhibition entitled ‘Lee Ungno & Park In-kyung Duo Exhibition: Artistic Companions in Life’. The exhibition was presented at Art Basel Hong Kong from Mar. 26 – 30, 2025, shedding new light on the artistic dialogue between the two artists and spotlighting Park In-kyung, one of Korea’s first-generation female artists whose contributions have long been overshadowed. Featured works included Lee Ungno’s People (1985) and Untitled (1979), which explore the sculptural beauty of calligraphic forms and Park In-kyung’s more recent works such as Bird (2024) and Rose (2024). While Lee captured the vigor and rhythm of human and textual forms with bold brushwork, Park took inspiration from petals, droplets, and minerals to depict more delicate elements such as poetic language on hanji with natural pigments and korean ink. Among her most celebrated works, Martin Calme (2006) evokes the quiet emergence of dawn through subtle variations of korean ink density. In Untitled (2024), she captures the essence of Korean ink wash painting through an oceanic blue ink washing over densely written text.

Park In-kyung sitting in her studio ©Choi BoYoung

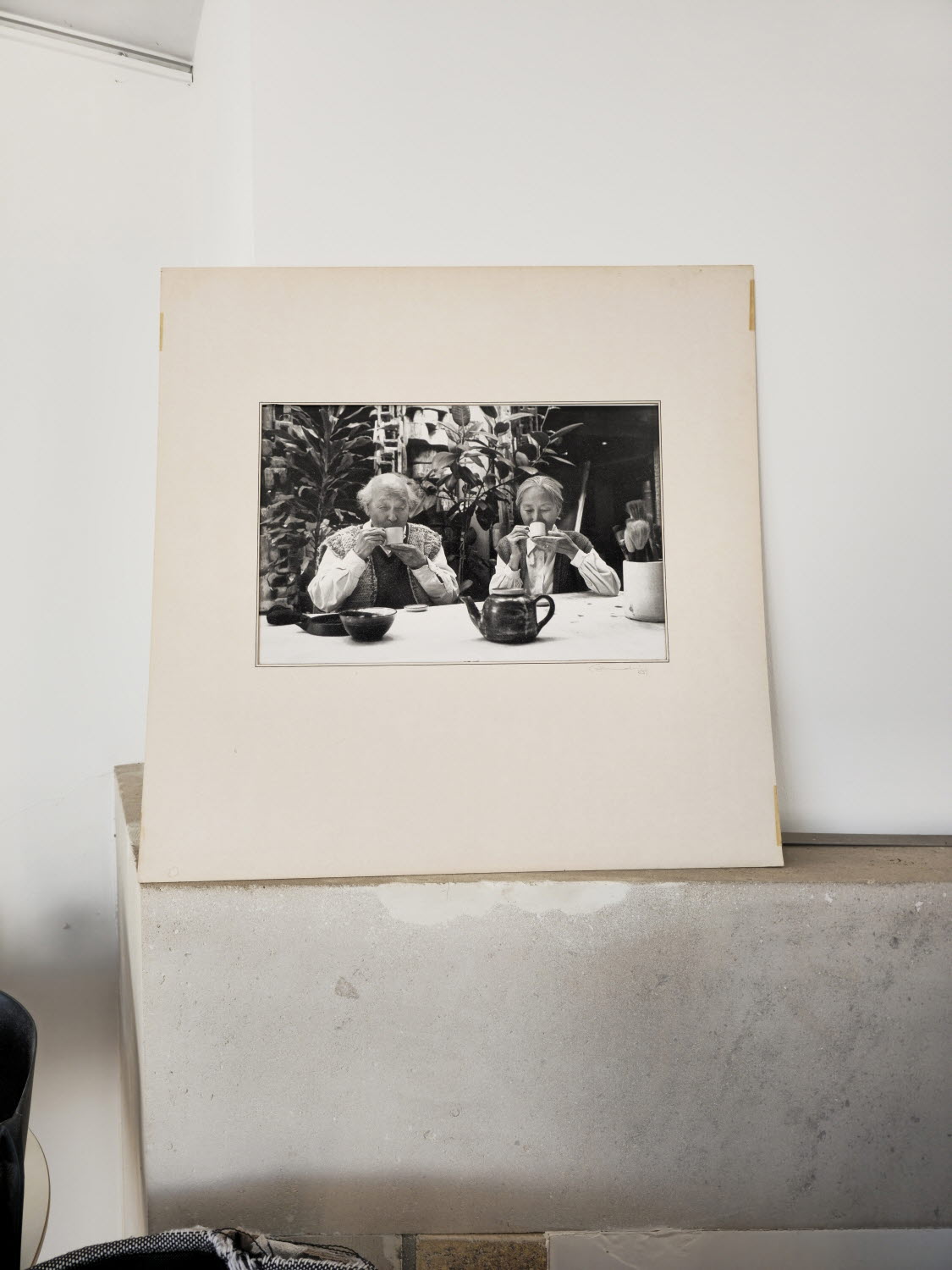

Photo of Lee Ungno and Park In-kyung ©Choi BoYoung