SPACE March 2025 (No. 688)

View of the colloquium ‘Postneoliberalism: ‘paradigm shift’ or ‘vibe shift’?’ / Screenshot from Youtube

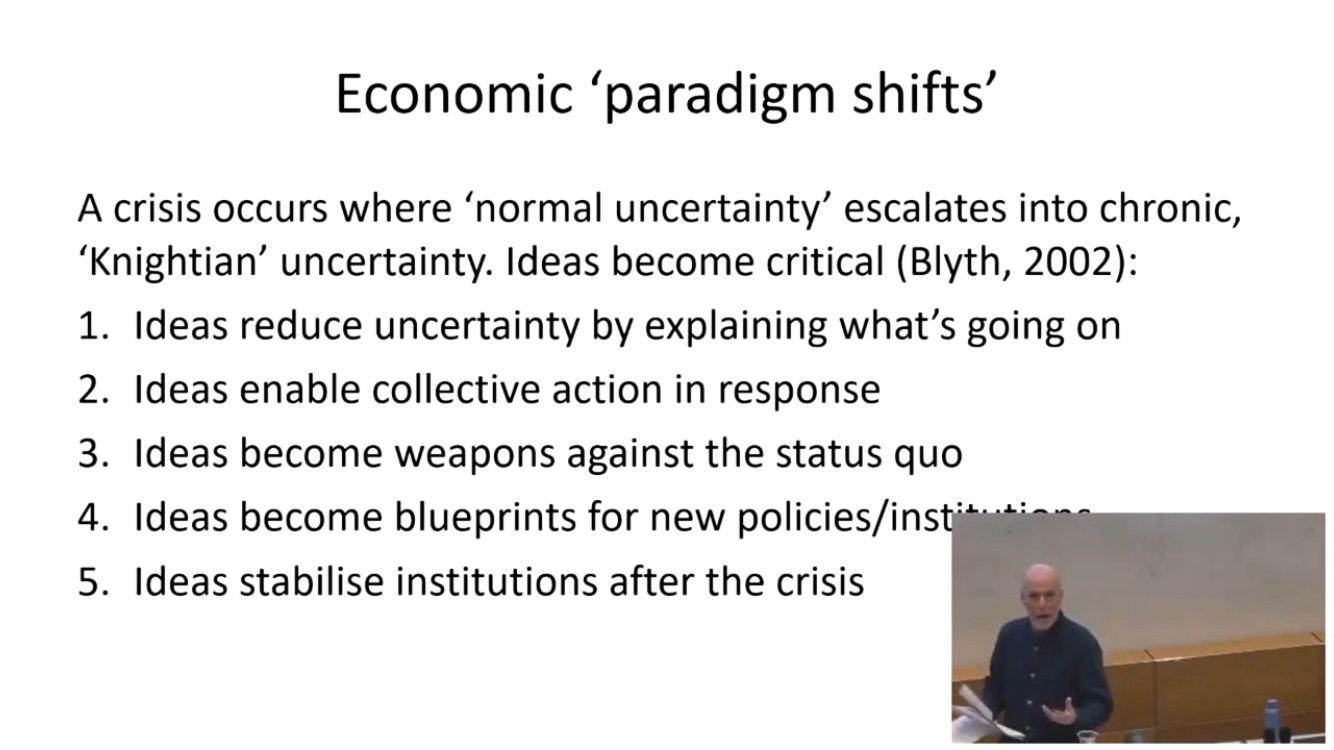

Presentation material of the colloquium / Screenshot from Youtube

What comes after neoliberalism? This question has been raised many times over the years, and in response to the Biden administration’s paradigm shift in economic policy, elite groups in the U.S. have already declared postneoliberalism to define the coming era. However, with the official launch of Donald Trump’s second-term administration, the failure of the existing neoliberal system to effectively address economic inequality, social instability, and sudden crises has once again highlighted the significance of this discourse. University College London (UCL) hosted a colloquium titled ‘Postneoliberalism: ‘paradigm shift’ or ‘vibe shift’?’ on Jan. 23, to diagnose our present moment, the limitations of our current system and to seek new possibilities for transformation.

Will Davies (professor of political economy, Goldsmiths, University of London) who led the presentation, examined whether today’s changes remain a mere ‘atmospheric change’ or signal a fundamental restructuring of the system in various aspects. He defined neoliberalism as an ‘intellectual and political project to remove barriers of market competition and to maximise the free activities of the private sector’. Key components of neoliberalism include expanding markets through privatisation and deregulation, minimising state intervention in international policy frameworks, and marketising non-market policies. He mentioned the distinction between ‘Quantifiable Risk (or Risk, as commonly used in economics)’ and the ‘Knightian Uncertainty’ that Frank Knight distinguished, and argued how our present understanding of neoliberalism was only focused on managing quantifiable risks when predictable and non-predictable risks co-exist within capitalism. Recent global events, such as the financial crisis, the pandemic, and Brexit, have all exposed the limitations of this approach, as governments have struggled to respond to crisis and fundamental uncertainties in real-time. Neoliberalism allows little room for proactive state intervention in times of crisis. Its basis is focused on minimising the risks themselves or shifting them elsewhere and is therefore making fundamental restructuring particularly difficult.

Historically, structural transitions have occurred through the emergence of new ideas and policies when existing theories failed to explain crisis. Professor Davies referenced Thomas Khun’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), when explaining the shift from a Keynesianism order to neoliberalism as ‘a shift in paradigm as Keynesianism faced an obvious anomaly of a stagflation in the 1970s’—a revolutionary paradigmatic transition triggered by the accumulation of anomalies. So, does today’s accumulation of anomalies guarantee a transition to a new paradigm? Davies sees that the present discourse around post-neoliberalism does not necessarily mean a complete end or replacement of neoliberalism, but rather a surface level ‘shift in atmosphere’. At the same time, he acknowledges that this very shift reflects the realities felt by the public. He emphasised that during political transitions, what is needed is not an elite-driven ‘reset’, but a more inclusive policy debate that incorporates public and real-life perspectives. For this, precise acknowledgement of economic and societal ‘atmospheres’ should be gathered through analysis of unconventional data such as real-time data, social media posts, and online opinions to manage unpredictable uncertainties. While the current phase may only represent an atmospheric shift, the collection and analysis of real-world data is essential for shaping the next stage of system restructuring. This colloquium was organised as part of the series ‘Political turning points, 2024 – 2025: Causes, consequences, solutions’.