SPACE September 2022 (No. 658)

SPACE No. 236 (Apr. 1987) ▶ e-magazine

Since its establishment, SPACE has shone a spotlight on Korea’s leading architects in various ways. Most representatively, they include a special feature on Park Kilyong (Apr. 1967) reviewed in the last ‘Re-visit SPACE 18’ (June 2022), and several special features on Kim Chungup and Kim Swoo Geun published into the 1980s. In the 1970s, SPACE published a series of special features: ‘The Image of Contemporary Architects’ dealing with Kim Hichoon, Lee Hitai, and Ra Sangjin; and ‘Overseas Korean Architects’dealing with six architects such as Kim Byunghyun, Ryang Dukkyu, and Kang Sukwon. And, in the mid-1980s, setting ‘Korea’s Contemporary Architects’ as the theme, it discussed ten teams of architects from Aum Dukmoon in March 1985, followed by Park Chunmyung, Kimm Jong-soung, and the Kim Jungchul and Jung sik brothers. ‘Architect Yoon Seungjoong’ (Apr. 1987), the sixth in the series, must be very meaningful from the viewpoint of ‘Re-visit SPACE’. That is because Yoon Seungjoong (1937 ‒ ) played a pivotal role in testifying to the situation of early Korean modern architecture and constructing its discourses. Working as a ʻchiefʼ under the command of Kim Swoo Geun in the 1960s, Yoon gave ʻlogicʼ and ʻorderʼ to Kimʼs ʻformʼ and used to provoke intense debate within ʻTeam Kim Swoo Geunʼ. With the establishment of SPACE in November 1966, such internal discussions were shared with the outside world and began to influence wider Korean architectural society. This was thanks to the direct and indirect presentation of ideas and remarks of Yoon Seungjoong and his teammates, such as Kim Won in the magazine. The first occasion was his roundtable discussion published in SPACE No. 3 (Jan. 1967), which concerned with the notion and influence of tradition triggered by the National Museum of Korea (the present National Folk Museum of Korea) competition. Establishing his own Wondoshi architecture office (later Wondoshi Architects Group) in 1969, he started to implement his idea of normative architecture across the work of his team, which he had developed from the standpoint of universality. As they were based on teamwork with his partners, we may say that his intellectual discussions were gradually internalised in his office and throughout the Korean architecture world. His ‘interest in the city and original things of architecture’ and intention ‘to recognise architecture like a city’ declared in his office name: ‘won’ (origin, foundation), ‘doshi’ (city) and ‘geonchuk’ (architecture)▼1 are also the topics he addressed to the Korean architecture world.

SPACE No. 236, p. 85.

However, the context behind senior architect Yoon Seungjoong, which can be evaluated from our present viewpoint, was not exactly expressed 35 years ago in SPACE. Looking back on the middle-aged architect’s career, who was nearly 50 at the time, ‘Architect Yoon Seungjoong’ was emphasising ʻnew beginningsʼ from that moment on. This is true in both Kim Seok Chul’s interview with Yoon Seungjoong, centre of gravity for the entire section, and Min Hyunsikʼs critique added at the end. The ‘Korea’s Contemporary Architects’ series was structured based on the interview with the featured architect from the beginning. Printed conversations between architects are not big deal, but as the first feature ‘Architect Aum Dukmoon’ clarified, the series set ʻobservation of architectʼs inner worldʼas the main target, unlike the previous series which focused on the architectʼs profile and project images (compare it with the ‘Image of Contemporary Architects’ and ʻOverseas Korean Architectsʼ series). What was added to the interview was a brief profile of the architect and representative works, followed by an essay by the architect’s close acquaintance. Securing a ʻcritical distanceʼ is key for the piece to become a ʻcritiqueʼ as opposed to an account, and Min Hyunsik, a partner in Wondoshi Architects Group, who regards Yoon as his ʻteacherʼ, seems to have been sensitive to this. In his piece, ‘The Architect who Constantly Explores the Universality of Lifeʼ, he carefully expressed his critical view of Yoon’s lack of ʻunique visual vocabularyʼ and blurring of concepts due to his obsession with strict norms, while overall respecting the virtues of Yoonʼs architecture, such as universal norms and ordering systems. This is the context in which Min suggested the ‘new beginning’ that was expected from Yoon Seungjoong, and Kim’s interview with Yoon also clearly reveals this intention.

SPACE No. 236, pp. 86 - 89.

Letʼs take a look at this interview, entitled ʻYoon Seungjoong and Wondoshi Architects Groupʼ. Much of the content may not be new to readers who have read his recently published oralhistorypublication.▼2 Nevertheless, this SPACE interview is significant in that it expressed his career position and perception of the field at that time in a more condensed and vivid way. Moreover, it is worth noting that their conversation was led by Kim Seok Chul (1943 ‒ 2016), an architect who could also now be regarded as a subject of research. As always, the interview was largely carried out in chronological order. It covers Yoon Seungjoong’s architectural education in his college days (1956 ‒ 1960), his working experience of eight and a half years from 1961 for Kim Swoo Geun, and his career in Wondoshi Architects Group. What is outstanding in the plot of the story is the fact that the logic and order he sought to realise Kim Swoo Geun’s form, that is, his pursuit of ʻgeneral solution for architectureʼ was expressed in a relationship with Mies van der Rohe’s architecture. Yoon thought Miesʼs Lake Shore Drive Apartments (and even the Seagram Building) as the accumulation of Farnsworth House, expanding it into a relationship between ʻhumanized unit spaceʼ and ʻinfinite spaceʼ. To him, this was the ʻprinciple inherent in architecture that governs the wholeʼ. (This also reflects his interests in cosmology ‒ one of his college courses ‒ and Japanese architects’ Metabolist idea). Interestingly enough, in relation to the Miesian idea, he looked back to his sophomore year in college when he formed a study group to read Sigfried Gideonʼs Space, Time and Architecture and gave a presentation about Mies. An interpretation of Mies’s architecture may be different. However, it seems clear that he could play a pivotal role in architectural discussions in Korea ‒ not only within ‘Team Kim Swoo Geun’ but also in the Korean architectural society in general ‒ because he had been a serious student of architecture since his school days. Because of this background, he was also able to play the role of a witness to early modern architecture in Korea. ‘Modern Architecture and Contemporary Architecture in Korea’, an article he published in the 200th commemorative issue of SPACE (Feb. 1984) is a case in point. This article tells the story, from the perspective of an architect who learned field experience, of how Korea has accepted and transformed Western modern architecture since the 1950s. It is still quite rough and requires several layers of dialectics, but it is an important reference point in Korean modern architecture.

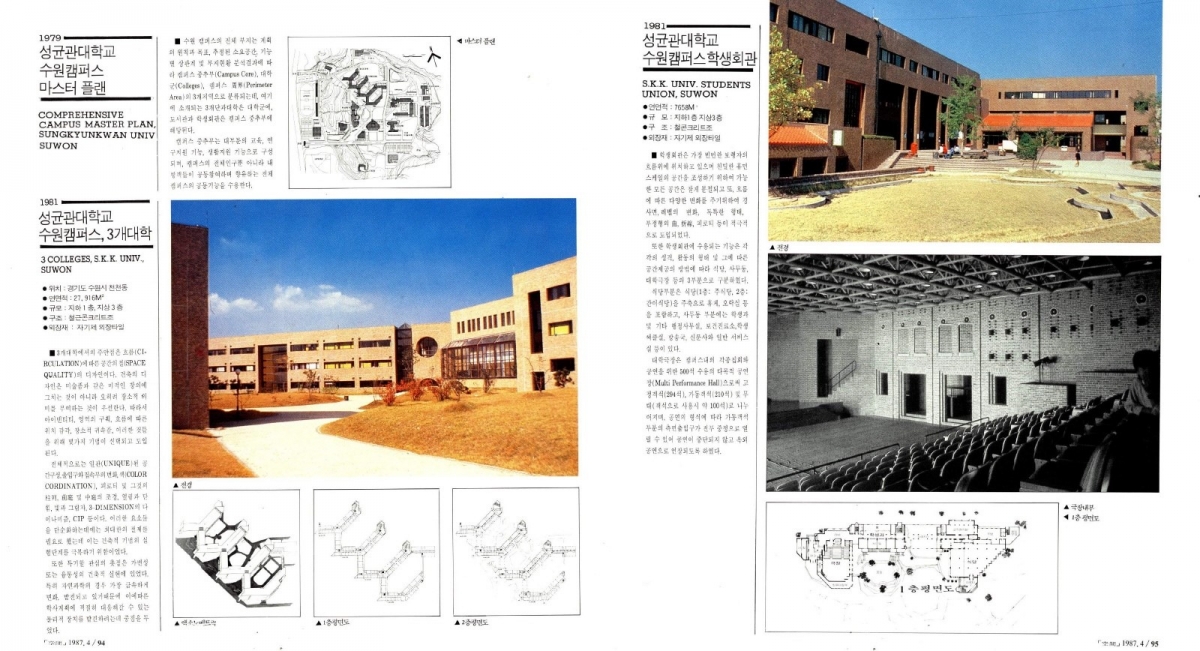

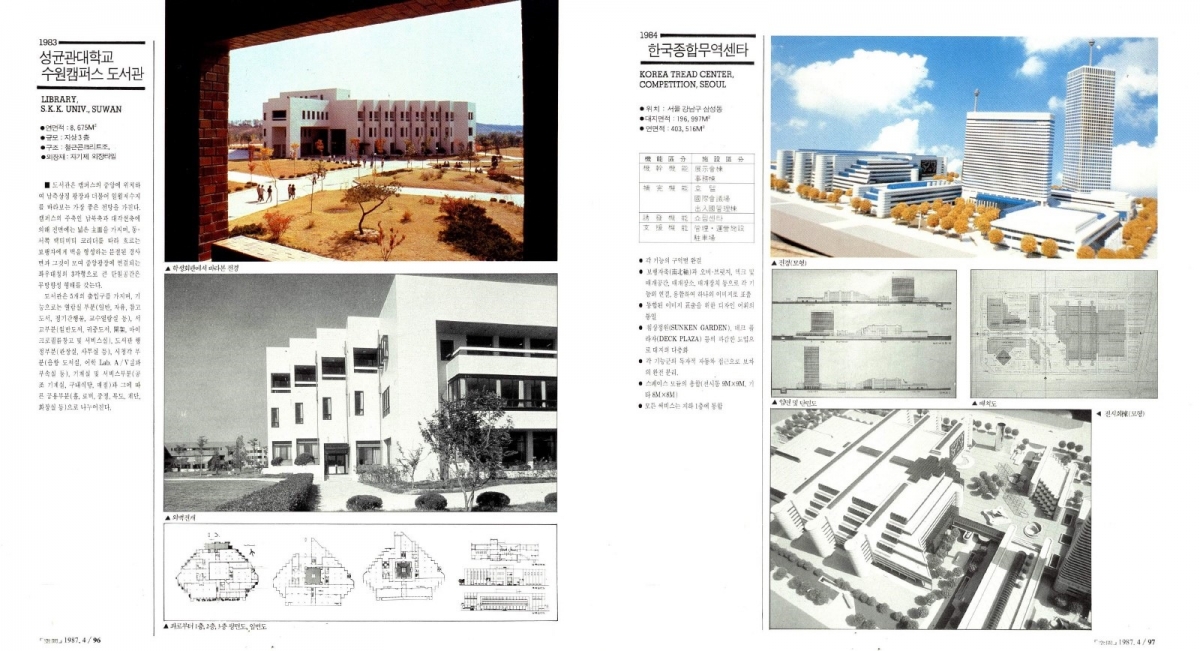

SPACE No. 236, pp. 92 - 95.

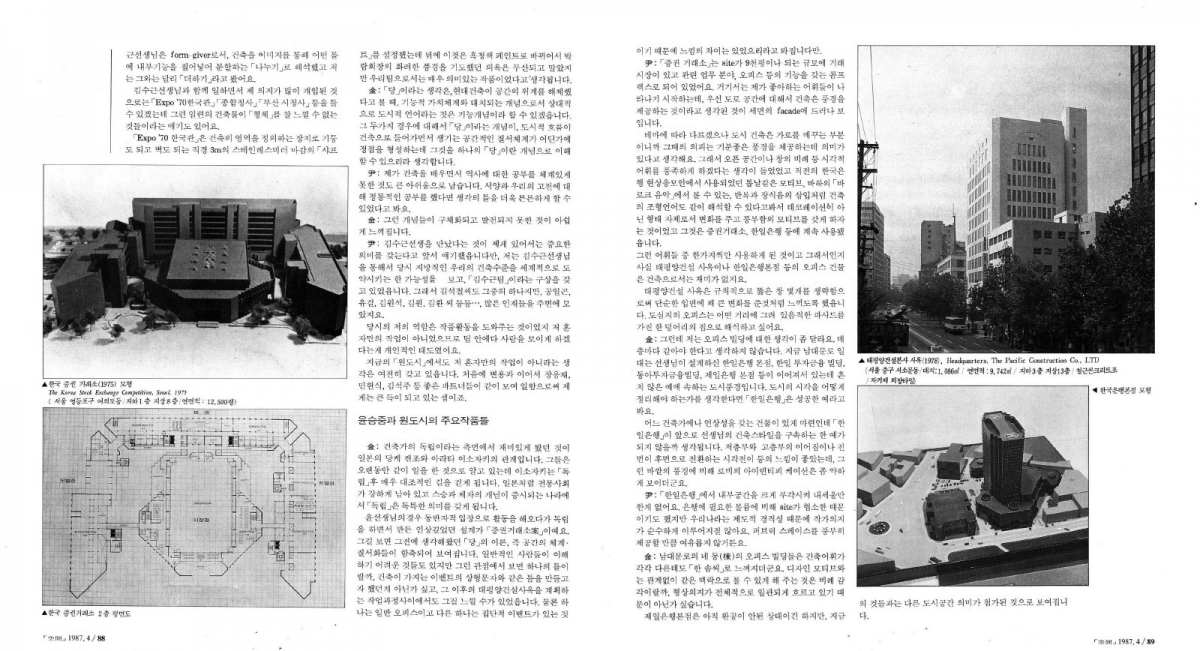

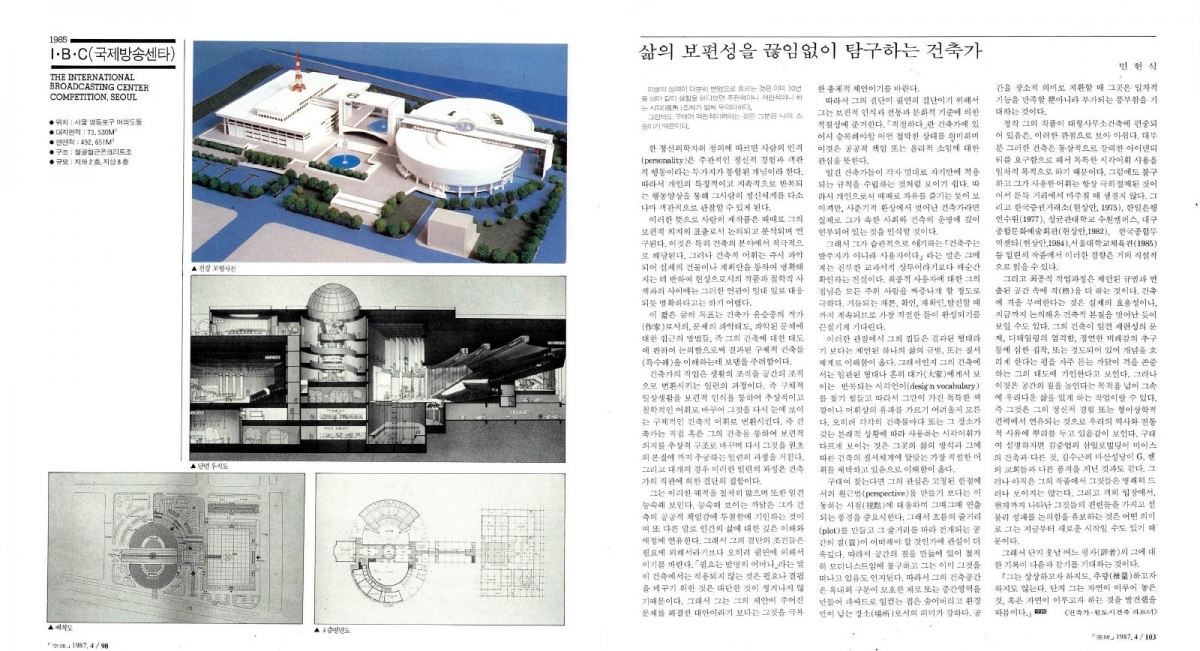

Returning to the interview, what is even more extraordinary here is that the concepts of ʻdangʼ ‒ originally meaning a dignified house ‒ and of ʻurban language’s intervention in architectureʼ became associated with Yoonʼs architecture, ever since working with Kim Swoo Geun. These concepts were set up by Kim Seok Chul, who led the conversation. For Kim Seok Chul, who belatedly joined Kim Swoo Geunʼs team after working in Atelier Kim Chung-Up, the two concepts may have looked much more conspicuous. Enumerating buildings that fit the concepts, he considered the ‘Korean Pavilion of Expo ‘70 in Osaka’ as the right example that demonstrates the two. After that, he defined, ‘the spatial order system created by urban flow into architecture forms a vertex somewhere, and we can understand it as the concept of a “dang”’—in a much clearer way than Yoon Seungjoong who was somewhat ambiguous about the ʻverbalisationʼ of the concept ʻdangʼ. Kim Seok Chulʼs interest in Yoon’s ʻdangʼ was developed into reading this concept through the projects of Wondoshi Architects Group, such as the Korea Stock Exchange (1975) and the International Broadcasting Center (1985).At this point, we need to recognise that Yoon’s ʻdangʼ came from ʻMajor Spaceʼ highlighted in the first issue of SPACE, although the architect himself did not reveal its origin. As I explained in detail in ʻRe-visit SPACE No. 13ʼ (Jan. 2022), the idea of ʻmajor spaceʼ, taken from the American magazine Progressive Architecture, can be interpreted in various ways in light of a Korean context. Naturally, it was explored within Kim Swoo Geun’s team (who was involved in the publication of SPACE) and eventually by the chief of the team Yoon Seungjoong—under the name of ʻdangʼ. Letʼs consider the other interviews he conducted for Ggumim (Feb. 1981) and Pro Architect (July 1997), where Yoon explained this concept a little more actively than in the interview with Kim Seok Chul for SPACE. The word ʻdangʼ, with which he was obsessed, directly refers to ʻmajor spaceʼ, and can be understood as a large and central space. When a domain is composed within it, order or hierarchy are created, and it is possible to ‘connect exterior public spaces on an urban scale into the interiors of architecture’. Then, he asserted that ‘architecture itself includes an urban organisation’, and as a result, ‘the city becomes architecture’. This concept was actively developed in the Government Complex project (1967) and Busan City Hall project (1969) ‒ which were the least influenced by Kim Swoo Geun ‒ in the period when ʻTeam Kim Swoo Geunʼ merged to become part of the Korea Engineering Consultants Corporation, and was continued in the projects of Wondoshi Architects Group. However, both ʻmajor spaceʼ and ʻdangʼ are very universal concepts in a way, it seems that there is a limit to the extent to which they may become unique architectural vocabularies when applied to buildings in practice. Most of all, since Wondoshi Architects Group tended to carry out large-scale projects, many defining logics, including the concept of ʻdangʼ, could easily become estranged from human sensibility. Moreover, teamwork, one of the apparent advantages, could limit individual vision of an architect. These are probably the reasons why Yoon Seungjoong himself experienced some doubts concerning the identity and mannerism of Wondoshi Architects Group, despite their achievement of ‘good’ architectural results. Yoon concluded the conversation by revealing his strong ambition to create ‘great architecture’ beyond ‘good architecture’.

SPACE No. 236, pp. 96 - 98, 103.

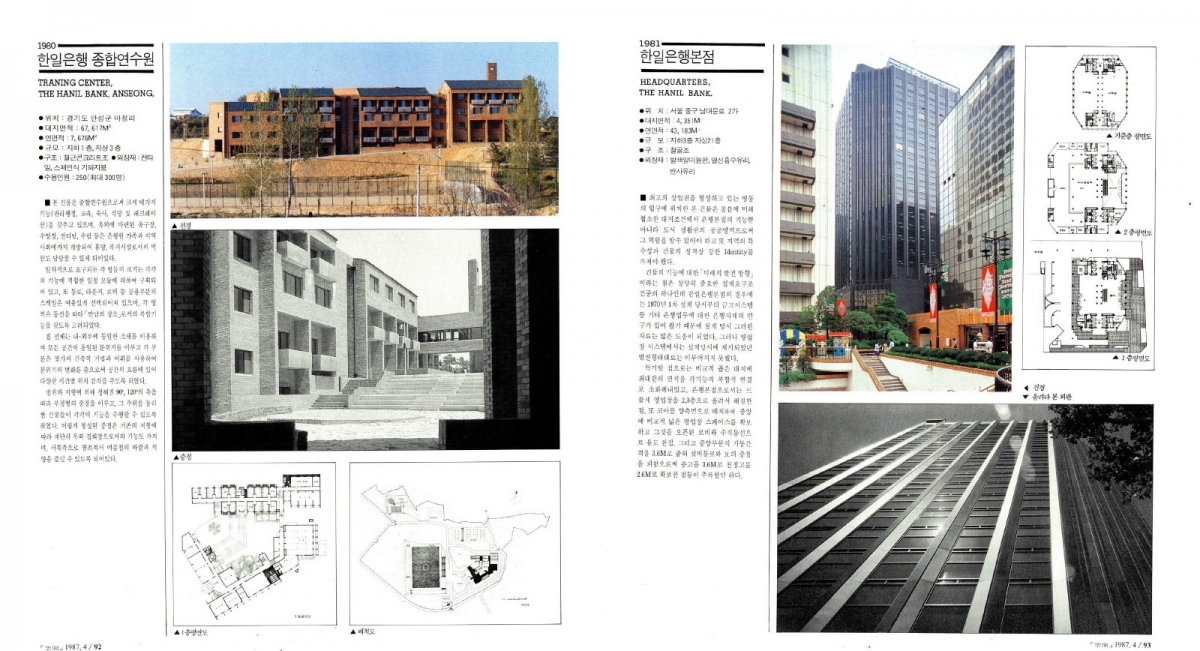

In the end, we come to realise that architecture needs something else that cannot be satisfied with the universal and normative, to borrow Kim Swoo Geun’s words, ‘rational’.▼3 ‘Visual vocabulary’, emphasised by Kim Seok Chul and mentioned by even Min Hyunsik, may be one of them, but this was a secondary issue for Yoon Seungjoong, who gave priority to ‘logic’ over ‘form’. Regarding the form, the ‘saw-tooth motif’ seems to be the most distinct visual vocabulary in Yoon’s architecture, which was impressively realised at the Headquarters of Hanil Bank (1981), and its variations were used in buildings like Sungkyunkwan University Suwon Campus Library (1983). In fact, Yoon Seungjoong’s idea of ʻadditionʼ (adding spaces to satisfy requirements of function) which was proposed in response to Kim Swoo Geunʼs ʻdivisionʼ (dividing interior space in a fixed form) had already included the possibility of creating a new form in light of organic tradition of European modernism. Nevertheless, it seems that Yoon’s failure of further development in morphological possibility was due to the restrictions of the times in the Korean context, unable to push an idea to its conclusion.Despite these reservations, the significance of the architect Yoon Seungjoong is not minimal. He is a figure who established an intellectual base in Korean architecture for his juniors to further advance—bridging the wide gap between special solutions provided by prominent seniors such as Kim Chung-up and Kim Swoo Geun in the developmental stage of modern architecture in Korea, from a viewpoint of general solutions for architecture. Of course, the fact that he contributed to the establishment of modern architectural discourse in Korea also underpins this background, as this article notes from the beginning. If borrowing the exhibition title of Yoon Seungjoong in 2017 at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, his role was no less brilliant in ʻconstructing sentencesʼ than drawing buildings.▼4 Thatʼs why itʼs necessary to contemplate the sentences and spaces between the lines in this special feature ‘Architect Yoon Seungjoong’.

In our next issue, Park Junghyun will deal with the special feature ‘Architecture in Transition’ covered in SPACE No. 53 (Apr. 1971).

------

1 Yoon Seungjoong · Byun Yong × Lee Sanghae, ʻInterview with Architect Yoon Seungjoong · Byun Yongʼ, Pro Architect 4 (July 1997), pp. 24-40.

2 Refer to Mokchon Architecture Archive’s Yoon Seungjoong’s Oral History (MATI BOOKS, 2014). In fact, Architecture in Urbanism (Ganyang, 1997), Yoon Seungjoongʼs essay collection published much earlier, had already provided an overall understanding and profile of him. It included this interview for SPACE, and some other interviews up to that time.

3 ‘Youʼre still under the influence of the rational’. Kim Swoo Geun commented on Yoon Seungjoong’s work in the early 1970s. Yoon Seungjoongʼs Oral History, p. 534.

4 ‘Yoon Seung-Joong: Constructing the Sentence of Architecture’, Korea Contemporary Artists Series, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, April 14 ‒ August 6, 2017. An exhibition catalogue with the same title as the exhibition has been published.