The UK operates Listed Building registration to protect its architectural heritage, and structures are ranked in the order of Grade 1, Grade 2*, Grade 2 depending on their significance. Recently, Clifford’s Tower, Grade 1 Listed Building in York, was opened to the public following a period of renovation. Hugh Broughton Architects (principal, Hugh Broughton), who were in charge of this project, have worked on a number of projects targeting historical buildings, each of which takes a flexible attitude to design, such as restoration, additions, interventions, or extensions depending on the site conditions. Here, we have the opportunity to follow Hugh Broughton and his architectural interventions into culturally signficant properties.

Clifford’s Tower

Hugh Broughton principal, Hugh Broughton Architects × Han Garam

Han Garam (Han): Following in the steps of Hugh Broughton Architects, one notes that a significant number of its projects have focused on British architectural heritage sites. In this interview, I’d like to attend to Clifford’s Tower (2022), the Painted Hall (2019), and the Maidstone Museum East Wing (2012). Let’s start with the most recent, Clifford’s Tower. This project began as a commission from English Heritage—I’m curious to learn more about the tower’s historical value and the aims behind this project.

Hugh Broughton (Broughton): Clifford’s Tower is the largest surviving structure from the medieval royal castle of York. At first, there was a timber tower here, and the stone tower was built in the mid-thirteenth century. In the seventeenth-century, a fire destroyed the interior of the tower. Clifford’s Tower is one of English Heritage’s top-ten most visited sites in the UK. The tower offers superb views over the city, but previous facilities were poor, and visitors often described their experience as ‘underwhelming’. The aim of the project was to address these shortfalls in experience and to improve visitor facilities at the tower, alongside carefully conserving the existing historical fabric.

Han: Clifford’s Tower was designated as a Grade 1 Listed Building. Project-wise, what were the restrictions in light of this status?

Broughton: As a Grade 1 Listed Building and Scheduled Ancient Monument, Clifford’s Tower is a significant structure subject to the highest levels of protection assigned by Historic England. The inserted timber structure required both planning permission and Scheduled Ancient Monument consent before work could begin on-site. The significance of the existing structure was evaluated, and the benefit and impact of any proposed changes carefully assessed. Throughout the project a careful balance was required to minimise the impact on the existing structure and increase the intellectual and physical access to the monument through the new interventions.

Han: To improve the environment and functioning of Clifford’s Tower, an entirely new structure was inserted. Assuming that the priority was to minimise affecting the original architecture itself, could you explain specifically how this dilemma came to be resolved?

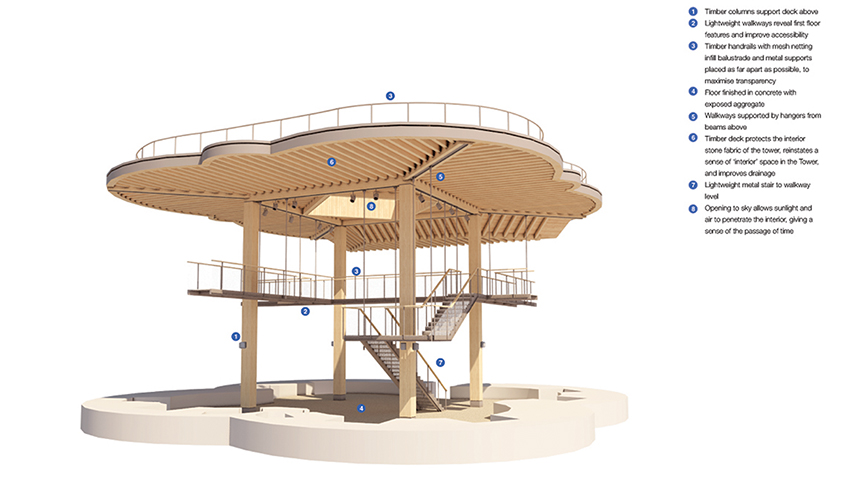

Broughton: We wanted the new structure to appear light and to contrast in visual terms with the existing stone walls, which is what drove the decision to use timber for the new canopy, roof deck and lightweight walkways suspended from its structure, alongside its renewable properties. The structure is supported by four Douglas fir glulam columns which rest on a shallow concrete raft foundation that evenly spreads the load without impacting on the archaeology of the tower. Columns at ground level mean the double height nature of the stone walls is still legible, with the highly engineered timber contrasting with the irregularities of the existing fabric.

At roof level the timber joists over sail and shelter the existing internal wall tops and bear onto a low-level plinth cast over an existing perimeter concrete ring beam, installed in the first quarter of the twentieth century. This also elevates the roof deck to the level of the original wall walk, which was 70cm higher. The edge of the roof deck is set back from the tower outer walls, giving visible breathing space to the historic fabric.

The new timber and metal insertions were prefabricated off-site, assembled and lifted into place using a mobile crane, which helps them to read as wholly reversible interventions that could be removed with limited impact on the existing structure.

Clifford’s Tower

The new timber structure of Clifford’s Tower

Han: Aside from adding a structure that stands in contrast with the original tower, there were also a number of works performed to restore the tower’s original image.

Broughton: Detailed conservation work has been carried out stone by stone, with historical features such as the heraldic plaques and ogee arch detailing fastidiously repaired and cleaned by a team of highly skilled masons and conservators. The chapel in the tower’s forebuilding has been re-roofed to prevent rainfall on the wall tops percolating through the structure causing efflorescent salts and evaporation leading to stonework decay. Careful poultice cleaning of the chapel arcade and interior ashlar stonework was also undertaken alongside repointing of the arrow loop reveals and stone indent repairs to the bartizan stair steps. The works sought to conserve and repair but also to impact the existing fabric as little as possible and clearly present its chronology, for example the fire scorched pink stonework that is still visible as a result of a fire in 1684.

Han: Ultimately, how has the experience of Clifford’s Tower changed?

Broughton: The addition of the new stairwell and walkways enables visitors to access areas of the tower previously unseen for hundreds of years, including the Royal Garderobe (latrine) and bartizan (turreted) stairs. Enhanced interpretations of spaces have been provided across all of the floors, relaying stories of the tower’s history, while the physical access up to the motte and into the tower has also been improved. Additional handrails and rest points have been added to the sides of the existing access stairs, and an enlarged public area at the base of the motte offers a ground level place to engage visitors and incorporates accessible interpretation, including a bronze timeline and a tactile map to assist visitor access.

Clifford’s Tower

Han: I heard that a number of unforeseen situations emerged. During the preservation and restoration work for the Painted Hall of Old Royal Naval College in the UK, the remains of a palace was discovered in the basement. When such cultural heritage or historical sites are discovered in the UK, how can the work proceed?

Broughton: Once a historic structure is uncovered as part of a construction project the work in the vicinity of the remains will halt while archaeologists and Historic England assess their importance. Various options may be considered including full excavation, conservation, and revelation to the public; re-burying or adapting construction to span or preserve the remains. In the case of our project at the Painted Hall, the remains of Henry VII’s Tudor royal palace were exposed. They were carefully conserved and then revealed to visitors as part of the interpretation design, helping visitors to appreciate the multi-layered history on the site.

Han: Cooperating with third parties also provide significant contributions to works related to architectural heritage.

Broughton: Martin Ashley Architects are specialists in the conservation of historic buildings and structures. We team up with them to ensure the highest standards are adopted and to ensure the protection of historic fabric for the enjoyment of future generations. In Clifford’s Tower, they were responsible for the preservation of the tower as mentioned earlier. In the Painted Hall, they are surveyors of the fabric added to the palace.

Painted Hall ©James Brittain

Painted Hall ©James Brittain

Han: Of the different architectural directions taken towards the preservation of architectural heritage, other than the aforementioned insertion and restoration, one cannot exclude extension. Maidstone Museum East Wing is a horizontal extension project conducted on a museum that was built in 1858 by remodeling a manor from the sixteenth-century. What were the main focal points in its design?

Broughton: The project at Maidstone Museum reoriented the main entrance towards the town centre; devised a new shop and education facilities for students of all ages; improved access with the introduction of a new stair and lift; improved the storage facilities for artworks and precious artefacts; and created new exhibition space. The new facilities are housed in two extensions clad in gold copper allow shingle and frameless glazing, which both contrast with and complement the original architecture. The project employs a ground source heat pump and solar photo voltaic panels to reduce carbon emissions and ensure the most sustainable design possible.

Han: As a Grade 2 Listed Building, Maidstone Museum is ranked lower than Clifford’s Tower. But the extension had a wider working range when compared to interior remodeling. On what do you place particular focus when conducting extension projects?

Broughton: The differing levels of protection are determined by experts from Historic England who inspect structures and then agree the level of listing. Maidstone Museum is Grade 2, Clifford’s Tower is Grade 1, so therefore subject to a greater number of restrictions in terms of the scope of the renovation. When designing extensions to historic structures we ensure that the new proposals respect the height, volume and material palette of the original architecture. This does not mean that they should copy the historic building—often contrast with the existing architecture brings out the best of both old and new. This was definitely the case at Maidstone Museum East Wing.

Han: I’m curious if there are other means of protecting architectural heritage sites in the UK other than the Listed Building system. What trends have you observed among recent projects concerning UK-based architectural heritage sites?

Broughton: There are other bodies in the UK with interest in historic buildings such as the National Trust and many local civic societies, however the statutory protection is managed by either Historic England, Historic Scotland or Cadw in Wales alongside the conservation teams of local authorities. Protected buildings span all ages from pre-historic archaeology through to post-war architecture. Protection maintains the original architectural qualities but does not drive the use of the buildings. The variety of use is great from railway stations to offices to housing to ruins so there is no rule on how these buildings are used.

Han: While this interview has centred around architectural heritage, Hugh Broughton Architects is also involved in designing cutting-edge facilities in extreme regions, such as the research stations in Antarctica. One deals with the past, while the other deals with the future—and so the common points between the two are not so obvious. Is there something mutually complementary as you go back and forth between projects of these two extremes?

Broughton: Both building types are concerned with protecting sensitive environments with sustainable and contextual solutions. They require a fastidious attention to detail and careful consideration of construction techniques and logistics. In architecture we are often transferring lessons learned from other projects and other aspects of life, so I see these two architectural types as mutually inclusive.

Maidstone Museum East Wing ©Hufton + Crow

Maidstone Museum East Wing ©Hufton + Crow

Maidstone Museum East Wing ©Hufton + Crow

Hugh Broughton

Hugh Broughton is a British architect who specialises in the design of buildings and structures in sensitive and remote locations. His practice has designed contemporary interventions within some of the most important historic buildings in the UK. Hugh Broughton Architects are also leading designers of science research facilities in polar regions, and have designed facilities for the UK, New Zealand, Australia, Spain and the USA.

1