ʻI am an Architectʼ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

interview Lee Haedeun, Choi Jaepil co-principals, o.heje architecture × Choi Eunhwa

We Live in an Old House in an Old Neighbourhood

Choi Eunhwa: You are use a hanok in Seochon as both your office and home. When did you settle down here?

Choi Jaepil: The first time we came to Seochon was when we were working at Samuso Hyojadong, an architectural firm. Then we went to Japan to study, and when we came back to Korea, we stayed in Hannam-dong for a while but soon returned to Seochon. We have been living and working in this town for about five years. This is the second space we have occupied.

Lee Haedeun: We wanted to live in a remarkable walking village. We think a good place in which to walk is one with no cars and parking lots but with life to observe going on in the first floors of its buildings. We hoped that the way people lived would naturally melt into the street, where people would put chairs and pots in alleys. We were able to fall upon many such charms when travelling around Seochon.

Choi Eunhwa: What is your life in a hanok like?

Lee Haedeun: When I first stayed in a hanok, I couldn’t sleep because of the overwhelming impact of the rafters. It felt like I was lying in a whale’s stomach! I also couldn’t get used to level of outside noise inside the house at first. I’m thinking about my reasons while living in the house, and I think it’s because the hierarchy of the roof is solid in a hanok. The pillars, beams, and all subsidiary materials exist to support the roof, and the structure is exposed as it is. A hanok does not have room as a unit, such as living room or bedroom, but consists of kan (bay). The size and number of bays are also determined by the scale of the roof. As a result, the existence of the wall is bound to become smaller. So, sound and air flow in and out freely. Even people easily come and go horizontally, so I feel closer to the neighbourhood.

Choi Eunhwa: Did you encounter any difficulties when situating both work and life in one space?

Choi Jaepil: In the most cases, the spaces for work and life were divided clearly, but we wanted to put them together. We thought that our lifestyle was similar to the way people used to live in hanoks 100 – 150 years ago; there was no distinction between hobbies, work, and life. Each one works alongside the other just fine, even though there are no boundaries. The area is about 85m2. Although the size is small, the sense of transition from one place to another is straightforward.

Choi Eunhwa: I have to ask you for your thoughts on a positive ‘work-life balance’. (laugh) What is the work-life balance of o.heje architecture (hereinafter o.heje)?

Choi Jaepil: I fully sympathise with and understand the feelings of working people. (laugh) However, our lives, work and life are profitably integrated. The very fact that a work-life balance is under discussion here means there is a perception that work and life exist in opposition, but we have lived in work and worked in life.

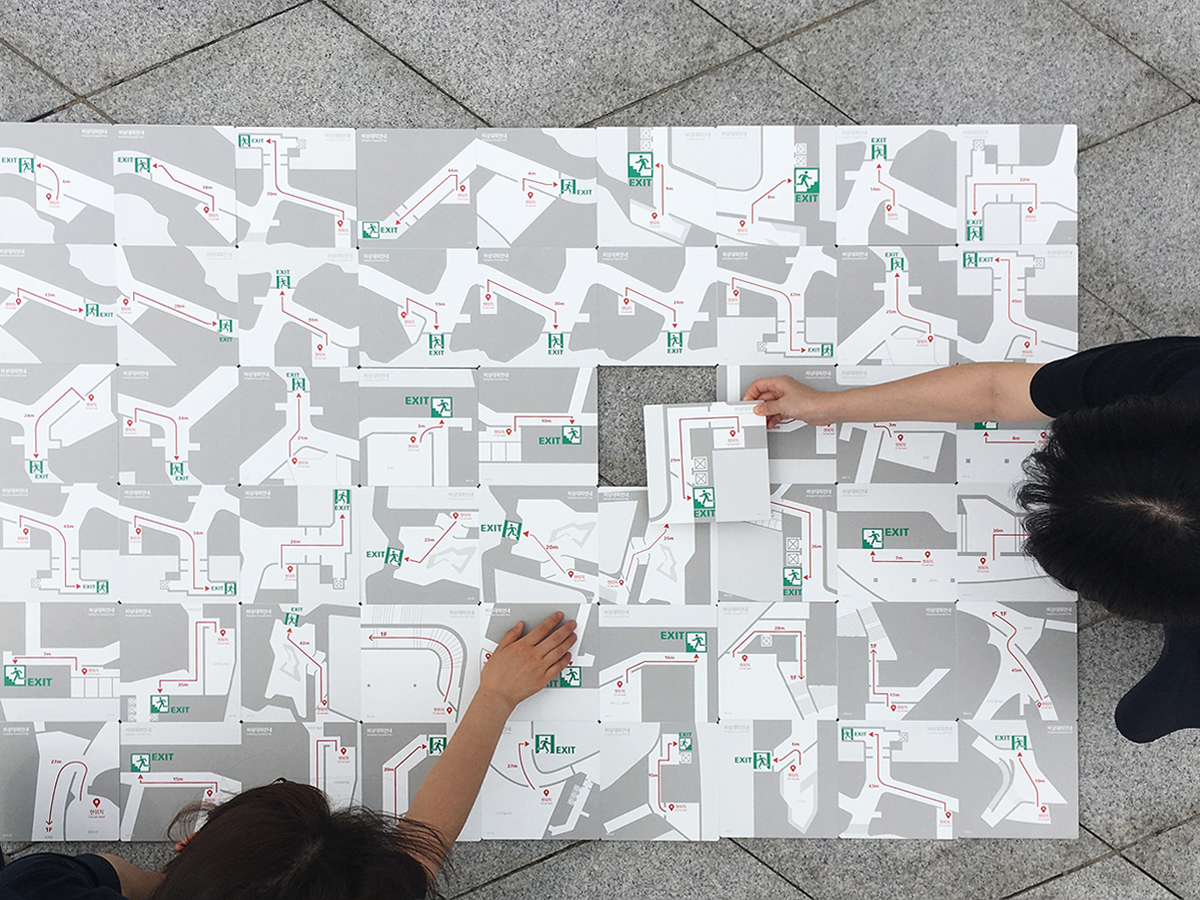

DDP Signmap ⓒo.heje architecture

DDP Design Library

We Observe Things and Embody Them

Choi Eunhwa: I think ‘work-life blending’ is a more appropriate concept for o.heje. There is a reason what you see and observe while walking around the neighbourhood is connected to the architectural projects on which you work.

Choi Jaepil: We pursue ‘architecture that connects with the surroundings and becomes new environments’. If we simply say, ‘make architecture that connects with the city or the village’, this can be very abstract. It takes precise work to actually implement such intentions. I embarked upon field research while thinking about how and what to specify in my projects. This started at undergraduate, continued in Japan when studying at Tokyo National University of Arts, and continues to this day, so there are Tokyo and Seoul versions. We have documented a sense of ‘living sense of openness’ in old residential areas, substituted urban structures with architectural structures, and researched circulation. We recode them as photos, essays, and drawings.

Choi Eunhwa: This is not simply an observation log, but an essential task, collecting methods to actually reach the architecture towards which you strive. What specifically are you paying attention to? What is the ‘living sense of openness’ that o.heje is assembling?

Choi Jaepil: The city and architecture exist within a single frame while possessing a world of different characteristics, like reversible clothes that can be turned inside out and worn both ways. We collect materials from border areas, such as reflections on some part of personal life submerged in the city. We called this ‘private publicity’. In Tokyo, for example, it’s common to have a personal washing machine in the hallway of a mansion, and just like in the past, we gathered by the stream to do laundry. We are collecting the small private yet public spaces hoping that these will pose possibilities to today’s cities where there are almost no public places and that the boundary between cities and architecture could be more open and generous.

Choi Eunhwa: Taking pictures and writing may be enough, but you are also committed to drawing. I think you value this as another kind of embodiment.

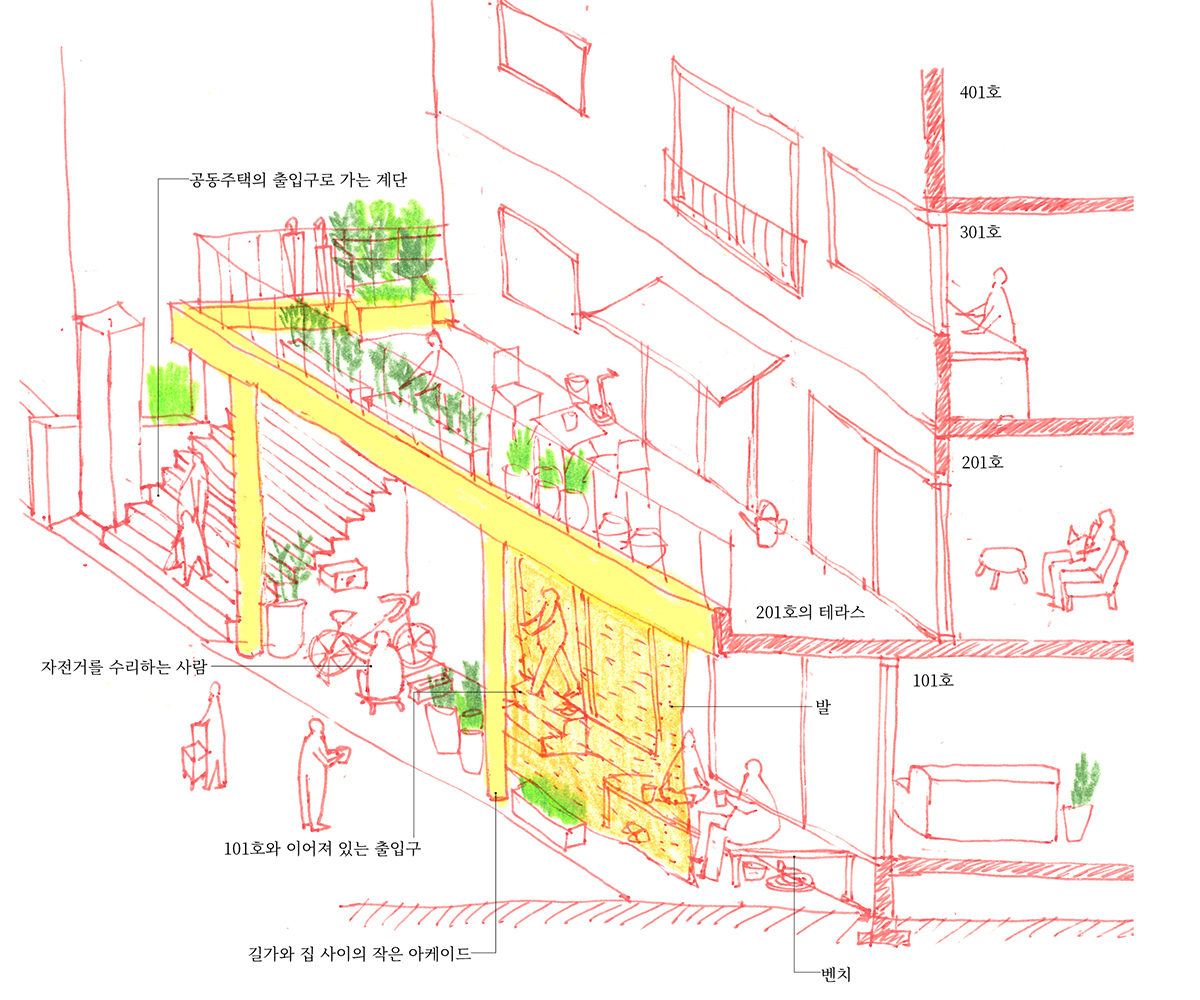

Lee Haedeun: You’re right. It is crucial. Most particularly, I get a lot of questions about why I draw with red pen. When working in Japan, I edited drawings with a red pen. So for me, the red line means the modification of an existing one. These drawings also do not depict scenes as they are but slightly modified or designed the existing urban structure. I draw as an intermediate process about what I see, what to collect, and how to bring it into my own in one place. It is not drawing to express and explain a particular impression, but drawing as an imaginative act in terms of what I can change in a given situation.

Drawing of ‘private publicity’ ⓒo.heje architecture

Hanok C ⓒo.heje architecture

I Draw a Red Line in a Given Situation

Choi Eunhwa: Not only are o.heje’s observations and works blended, but o.heje also blends city and architecture. It seems that such an approach can prove revelatory, as in the DDP Design Library (2018) on which you worked with Samuso Hyojadong. Inspired by the urban landscapes you observed in Japan, you presented works in which city, architecture, furniture, and objects are one.

Choi Jaepil: In Jimbocho, Tokyo, there is a street of second-hand bookstores. There are bookcases embedded in the façade of the building, and they can be opened and closed using a curtain. Not just one or two bookstores have this singular feature, but the entire street, and so the street becomes a book, a bookshelf, and a library. In general, the hierarchy between books, bookshelves, and libraries is clearly divided. There is a library building, bookshelves in it, and books on each shelf of the bookshelf. We began this project hoping that this solid hierarchy would be redefined. The bookshelf stands between urban and furniture scales, it generates the streets and open spaces like a courtyard. It can even act ads the façade of the building and as elements like chairs. We hoped that its impression as a building fades and only a scene created by people and books remains.

Choi Eunhwa: You also did other work for DDP. The DDP Signmap (2019) visualises which route to take in an emergency. How is it different from a normal evacuation map?

Lee Haedeun: This is a graphic work we created in collaboration with the design office Mirae Mulsan. Initially, the aim was to make an evacuation map. In fact, it was a simple in that all we had to do was draw an evacuation route with arrows on the floor plan. However, evacuation maps made that way can only be read by those trained to read drawings. We thought that the evacuation map had a stronger resemblance to sings than to maps, so we tried ‘singmap’ as a middle approach. It is closer to the mobile application which is autorotated around your location. You don’t need to find where the south is or to read the architectural drawings. Moreover, in DDP, it is not easy to read the space even if I, as an architect, try to find my way around through drawings. The difficulty is serious because the space and its organisation is different, and there is no obvious direction. In this instance, the design had to be more intuitive.

Choi Eunhwa: It is a visualisation of navigation, like a Google Map for each place.

Lee Haedeun: Yes, a total of 156 sign maps were produced. In each of the places, only three pieces of information were left behind: the current location, the emergency exit, and the route. We nearly lost the function of our wrists when drawing each and every one by hand but it was worth it. (laugh)

Choi Jaepil (left) and Lee Haedeun (right)

We Define the Two Through a Gradient

Choi Eunhwa: Please also introduce the work you are doing these days. The model over there is the Hanok C project under construction, right?

Choi Jaepil: This hanok is located in our neighbourhood, Seochon, and it was an urban hanok that had been divided and added to over the years. Two hanoks were placed in a figure 11 shape, and the space of concrete structure was sandwiched between them. We made them separate the structure and integrate the space. And we also planned one hanok for the external space and another for the internal space surrounded by walls and doors. In the centre of the house, there is a space that becomes a vast space within the room and a space within the yard, like the Daecheongmaru (main floored room) in a traditional hanok. It was planned to develop in stages from open spaces such as living rooms and kitchens to private spaces such as bedrooms. The project is currently under construction and is expected to be completed this year.

Choi Eunhwa: You are also working on a new construction project at the same time. House D is a detached house with two large roofs that intersect. The huge roof reminds me of a space like the stomach of a whale, that Haedeun talked about at the beginning of the interview. (laugh)

Choi Jaepil: This house will be built in the residential land development district of Dongtan. In most of these housing complexes, homogeneous houses are lined up to adopt the same form. It extracts the maximum area from the given site and divides the space. The living room is this much, the bedroom is this much, and so on. We are planning a house that is so far from that, and where the necessary spaces are united into one. It is not a divided space, but a space like a single environment, where family members can find a place of their own. The two roofs are positioned with a gap, and various spaces are layered in between, imagining the scene where people gather under a large tree and engage in multiple activities. It was designed with a low roof when you first enter the house and then to a square-like room with a high floor height of nine to ten metres. We are closely applying the steps from the external to the internal to the space.

Lee Haedeun: Simply stated, the yard is covered with a roof. Considering the climate of Korea, which has four seasons, and the situation of structures in a new city that are close to the house next door, I understood that the outdoor space would only be available for a few days a year. That’s why we created an open interior space, like the outside. I explained to the client that it was ‘a space where sunlight and wind pass through, but not rain’; and they liked it. Since the roof is essential in this project, our biggest challenge is how to make it more beautiful and intuitive.

Lee Haedeun and Choi Jaepil, our interviewees, want to be shared some stories from Hwang Dongwook in March 2022 issue.